Posts Tagged ‘GMO’

Blocking a new GM Trojan horse in India

On 15 November 2021, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) issued a draft regulation called the Food Safety and Standards (Genetically Modified or Engineered Foods) Regulations, 2021.

This draft regulation, through the medium of a regulatory agency (the FSSAI) is the latest attempt by the agricultural biotechnology multinationals and their Indian subsidiaries and partners to trick Indians into consuming foods made from genetically modified or genetically engineered crops. Altogether the opposite of protecting the citizen, the draft regulation of the FSSAI is a Trojan horse which, the industry has built and deployed to pave the way for the easier entry of GM foods into India.

The first section of my response to the FSSAI follows, and the full document is available as a file at the end of this post.

Section 1, intent of the regulations

At the outset, I completely reject modern biotechnology in India’s farming and food. There is no case now, and there never has been a case, for its inclusion, based both on sound science and on public interest. Genetically modified/edited seed and crop of any kind is a threat to the health of Indian citizens. It is a threat to the environment and to the existing agricultural biodiversity of India. It is a threat to the socio-cultural traditions that our agriculture and food rests upon. The Union Government of India and every state and union territory government must prohibit genetically modified/edited seed and crop. There can be no compromise on this matter.

What then is this draft legislation brought for? Nowhere in the text of the draft legislation do I find any reference to any work carried out by the FSSAI or commissioned by it from independent authorities, nor any reference to such work carried out by either the Ministry of Agriculture or the Ministry of Environment – as both these are subject areas associated with the subject of this draft legislation – that assesses the need for such products in India.

In the same way, nowhere in the text of the draft legislation do I find evidence of the precautionary principle applied. The precautionary principle is central to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety which India has ratified. Thus the precautionary principle is an obligation, hence a draft legislation about genetically modified or engineered foods must explicitly state that such foods manufactured from, and such foods that contain ingredients derived from (whether in small part or larger part) genetically modified/edited seed and crop will under no circumstances be allowed into India, whether by import of finished goods, or by manufacture (food processing) based on such ingredients or by cultivation within India.

There is a voluminous international record of more than 25 years which shows conclusively that GM foods carry with them biosafety risks during production and health risks during consumption. No Indian citizen should be presented such foods, in whatever form, for consumption. Vulnerable sections of the public such as infants, children, pregnant and lactating mothers, the elderly and people with existing morbid conditions should more particularly be protected from such foods.

I find there is no recognition whatsoever – let alone the provision to act upon such recognition – of these first principles in the text of the draft legislation.

Where something can cause serious irreversible harm, it is right and proper for scientists to demand evidence demonstrating that GM is safe beyond reasonable doubt. This is also an approach that is contained by the precautionary principle (for scientists and for the public, it is just common sense). Scientific evidence is no different from ordinary evidence, and should be understood and judged in the same way. Evidence from different sources and of different kinds has to be weighed and combined to guide policy decisions and actions. That’s good science as well as good sense.

Genetic modification/ engineering/ editing involves recombining, that is, joining together in new combinations, DNA from different sources, and inserting them into the genomes of organisms to make ‘genetically modified organisms’. GMOs are unnatural, not just because they have been produced in the laboratory, but because many of them can only be made in the laboratory, quite unlike what nature has produced in the course of millions of years of adaptation and change. Thus, it is possible to introduce new genes and gene products, many from bacteria, viruses and other species, or even genes made entirely in the laboratory, into crops, including food crops. We have never eaten these new genes and gene products, nor have they ever even been part of our food chain.

The artificial constructs are introduced into cells by invasive methods that result in random integration into the genome, giving rise to unpredictable, random effects, including gross abnormalities in both animals and plants, unexpected toxins and allergens in food crops, and unknown effects on humans and animals. This problem is compounded by the overwhelming instability of transgenic lines, which makes risk assessment virtually impossible.

None of these risks are acknowledged by the draft legislation which therefore fails completely to establish why in the first place the provisions and mechanisms it contains are needed or are suitable for India. It also fails as a protective legislation by not prohibiting foods based on or derived from genetically modified/edited seed and crop.

You can find a pdf file of the full document here, or an open document format text file here.

A scientist recants, or can he really?

M S Swaminathan during his fieldwork years, and today. Photos from MSS Research Foundation

During the dialogue between Maitreyi and the sage Yajnavalkya, the great sage in one of his answers to her difficult series of questions, explains what validity is. Yajnavalkya said that man-made law is temporal law, valid only as long as people who are concerned with it agree that it is valid; when not agreed upon, its validity ceases.

In one of his 1934 lectures J B S Haldane, one of the early 20th century’s founding evolutionary geneticists, and a political leftist, observed: “Put a Jersey cow and a South Africa scrub cow in an English meadow. The Jersey will give far more milk. Put them on the veldt, and the Jersey will give less milk. Indeed she will probably die.”

At 93, one of our scientists who is known for knowing about crops, is I am sure familiar with both, for he should have passed into the stage of sanyasa some years ago, in which stage he would profitably contemplate lessons from these and other thinkers. But the scientist seems strangely reluctant to do so, having had fashioned for himself a vanaprastha which resembles a field biology laboratory.

It has been fashioned for himself not by the kisans of India who are grateful for having carried out the results of his researches, but by the industries of food and the merchants of the technological cornucopia that surrounds all that we call food today. It is in short, a very elaborate golden handshake whose fine print contains a few tasks which Padma Shri Padma Bhushan Padma Vibhushan Monkombu Sambasivan Swaminathan has been entrusted with.

If he disregards the fine print, even today, he is scolded and upbraided by those half and even a third his age, for he is still governed by the proctors of industrial agriculture who pay not the slightest attention to the glittering heap of accolades and awards (73 honorary doctorates at last count) that accompany his name. And this is what happened when M S Swaminathan, as co-author of a rather reflective paper in the journal Current Science, questioned the sustainability, safety, and regulation of genetically modified crops.

Cows returning from their evening grazing, upland Tamil Nadu.

With that paper, he strayed across the Yajnavalkya boundary that marks out ‘validity’. He ceased being the English meadow in Haldane’s example and became instead the south African veldt. These are transgressions not permitted by the fine print that accompanies, along with awards and accolades, all scientists whose practice of science is determined by industry and foreign policy, as food and the cultivation of crop has been since the European monarchies funded the annexation of territories not their own to convert into colonies.

It is possible that Swaminathan and his co-author, P C Kesavan (a researcher at the M S Swaminathan Research Foundation in Chennai, India, which is the elder scientist’s field biology lab) were actuated by considerations other than scientific.

What might these considerations have been? First, political, because from around mid-year in 2017, a broad front of diverse groups – the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee – with several of its constituents claiming to represent kisan organisations and associations in different states, others including activist organisations protesting genetically engineered crops, have been launching marches and agitations against the NDA government using agriculture and kisan welfare as their platform.

The connection, between this episodic haranguing on the streets (not in fields) and Swaminathan is that he supplied, through the recommendations of the National Commission of Farmers (in 2004), their primary talking points today. Even today, his is seen as India’s most authoritative academic imprimatur on a campaign, programme or policy about sustainable agriculture.

It is a remarkable balance to have maintained for a man who helped usher into India an alien, short-stemmed, lab-tinkered, input-hungry rice variety to replace – with disastrous long-term effects on our agro-biodiversity and soil health – our own magnificent families of rice.

His second consideration for doing so is undoubtedly a blend – an academic setting right of the record, and an acknowledgement of the soaring unsustainability of industrial, fossil fuel-driven, retail oriented agriculture that relies on biotechnology and artificial intelligence. Any field researcher who tramped past rice seedling nurseries in the mid-1960s would absorb sustainability in all aspects of crop cultivation, sustainability should infuse his every utterance.

Picking cotton in Saurashtra, Gujarat. Bt cotton remains the only legally cultivated GM crop in India

But when Swaminathan was turned towards genetics, and away from the science of selection which our kisans have practiced ever since (and likely before) Rishi Parashar composed his smrti on the subject, he was parted forever from the simple essence of sustainability. Yet now there loom before the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, of which Swaminathan has been an éminence grise, the effects of climate change and the demands of the sustainable development goals, and modern agriculture cannot comply with even the skeletal interim standards of these goals.

For all his misdemeanours since the 1960s – including the unforgiveable plundering of our Central Rice Research Institute’s extremely valuable varieties from Odisha and Chhattisgarh, to stock the gene banks of the International Rice Research Institute with – I doubt that Swaminathan cares to be remembered by the generations to come in India as one of those who bestowed scientific legitimacy upon an agro-ecologically illiterate programme, the Green Revolution.

The lorry-load of awards he has accumulated over four decades have for the most part been supplied by the industry and nation-state powers that make food and its supply an economic weapon or a foreign policy instrument. That makes him not a visionary scientist receiving the admiration of multitudes (which the Padma awards were supposed to represent) but a paid general upon whose person battlefield decorations are pinned every now and then to please the troops.

He made his Faustian bargain nigh a half-century ago, but if a retreat into sanyasa and a twilight of less untruth than what he has guarded was Swaminathan’s wish, it is not one he will have granted. For swift and pitiless came the censure of his paper in Current Science. “The specific instances where results are selectively omitted, selectively represented or misrepresented are rife,” grated out K. VijayRaghavan, Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India, in his note to Swaminathan.

“Indeed, the bulk of the scientific points made in this part of the review have been raised previously and have been scientifically discredited widely and one has to only study the literature to see this.” Others, who have made similar bargains, on terms more demanding, were much more unkind and derisive.

The co-authors have been attacked for having “relied on papers and statements by individual scientists that run against the collective weight of peer-reviewed data and in-depth assessments by respected scientific organisations such as the Royal Society (UK), the National Academy of Sciences (US), the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority”. In short, for having deviated from the industrial-agri-biotech party line the international GMO politburo must enforce.

And so the elder scientist had to disavow his recantation, first to the government man: “There has been some misunderstanding about my views to ensure sustainable productivity by avoiding the spread of greed revolution resulting in the undermining of the long term production potential.” And likewise in a letter (on his foundation’s website) to the biotech industry’s army of invigilators the world over: “I wish to conclude by reiterating my total commitment and support to modern technologies including genetic modification and gene editing.”

This episode has shown that in some matters there can be no renunciation. Sri Krishna explained to Arjuna that under his direction and control, nature brings out this mighty universe of living and non-living beings and “thus does the wheel of this world revolve”. Fatefully, it seems that a sanyasa spent in contemplation of this wheel will elude M S Swaminathan, who once knew rice fields.

The deadly threat of gene drives

The UN Biodiversity Conference began on 13 November 2018 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, and until its close on 29 November will call on decision makers from more than 190 countries to step up efforts to “halt biodiversity loss and protect the ecosystems that support food and water security and health for billions of people”.

On 17 November, the Conference of Parties to the Cartagena Protocol of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity begins. On the agenda is a vital subject that has been moved to the centre of the meeting’s deliberations: a technology called ‘gene drives’. This part of the UN Biodiversity Conference will discuss several key draft decisions about the risks it poses and how to deal with them, including through a moratorium on the technology.

What are ‘gene drives’? Gene drive organisms are supposed to ‘force’ one or more genetic traits onto future generations of their own species. The term for gene drives used by French scientists, ‘Forçage Génétique’ (genetic forcer) makes the intention clear: to force an engineered genetic change through an entire population or even an entire species. If permitted, such organisms could accelerate the distribution of corporate-engineered genes from the lab to the rest of the living world at dizzying speed and in an irreversible process.

What are ‘gene drives’? Gene drive organisms are supposed to ‘force’ one or more genetic traits onto future generations of their own species. The term for gene drives used by French scientists, ‘Forçage Génétique’ (genetic forcer) makes the intention clear: to force an engineered genetic change through an entire population or even an entire species. If permitted, such organisms could accelerate the distribution of corporate-engineered genes from the lab to the rest of the living world at dizzying speed and in an irreversible process.

As a must-read explainer of this menacing new technology, prepared by the ETC Group and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung, has put it, such organisms “are designed, over time, to replace non-gene drive organisms of the same species in a population via an uncontrolled chain reaction – this ability may make them a far more dangerous biohazard than genetically modified organisms (GMOs)”. [The report, released in October 2018, is ‘Forcing The Farm: How Gene Drive Organisms Could Entrench Industrial Agriculture and Threaten Food Sovereignty’.]

Recently, a study by the Bundesamt für Naturschutz, which is the central scientific authority of the German federal government for both national and international nature conservation, warned that “with gene drives, GMO applications are moving directly from crop plants to modifying wild species. Major consequences on semi-natural and natural ecosystems are expected.” The research concludes that “a clear understanding

and analysis of these differences is crucial for any risk assessment regime and a socially acceptable and

ethical evaluation that is vital for the application of [GDO] technology”.

More pertinent to the current model of the transnational cartelisation of industrial agricultre, a group of French researchers recently concluded: “The time frame of gene drive perfectly fits the economic development strategies dominant today in agribusiness, with a focus on short-term return on investments and disdain for long-term issues. The current economic system based on productivity, yields, monoculture, and extractivism is a perfect match for the operating mode of gene drive.” [From ‘Agricultural pest control with CRISPR‐based gene drive: time for public debate’ by Virginie Courtier‐Orgogozo, Baptiste Morizot and Christophe Boëte in EMBO Reports.]

More pertinent to the current model of the transnational cartelisation of industrial agricultre, a group of French researchers recently concluded: “The time frame of gene drive perfectly fits the economic development strategies dominant today in agribusiness, with a focus on short-term return on investments and disdain for long-term issues. The current economic system based on productivity, yields, monoculture, and extractivism is a perfect match for the operating mode of gene drive.” [From ‘Agricultural pest control with CRISPR‐based gene drive: time for public debate’ by Virginie Courtier‐Orgogozo, Baptiste Morizot and Christophe Boëte in EMBO Reports.]

Reading these warnings helps form better clarity about what GDOs are and are not. From what I have been able to understand, normal reproductive biology gives the offspring of sexually reproducing organisms a 50:50 chance of inheriting a gene from their parents. The gene drives however is an invasive technology to ensure that within a few generations, all that organisms offspring will contain an engineered gene!

Why the phase shift from the already dangerous GMO to the threatening of an entire species by GDO? Thanks to rising consumer awareness of the dangers of GMO food crops, vegetables and fruit – which is now visible even in India (a generation-and-a-half later than Europe) where the central and state governments have put not a rupee into educating consumers about pesticide and synthetic fertiliser poisoning, let alone GMOs) – the uptake of GMOs is levelling off as the predicted risks have become evident, such as the intensification of the treadmill of increased use of toxic chemicals. The so-called ‘gene editing’ techniques, and particularly GDOs, has given the industrial agriculture-biotech-seed multinational corporations a strategy to regain the pace of their domination of food cultivation and therefore food control.

Recognising the extreme danger, the UN Biodiversity Conference which is now under way in Egypt, and particularly the part of the conference beginning on 17 November which is the Conference of Parties to the Cartagena Protocol of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), have placed gene drives on the agenda. [The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity is an international agreement which aims to ensure the safe handling, transport and use of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology that may have adverse effects on biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health. It was adopted on 29 January 2000 and entered into force on 11 September 2003.]

The meeting will discuss, under ‘Risk assessment and risk management’ (which are Articles 15 and 16 of the Protocol) draft decisions on gene drives and, we must hope, take them while imposing a moratorium on this evil technology. [Draft decision document CBD/CP/MOP/9/1/ADD2]. The draft decisions are:

3. Also recognises that, as there could be potential adverse effects arising from organisms containing engineered gene drives, before these organisms are considered for release into the environment, research and analysis are needed, and specific guidance may be useful, to support case-by-case risk assessment;

3. Also recognises that, as there could be potential adverse effects arising from organisms containing engineered gene drives, before these organisms are considered for release into the environment, research and analysis are needed, and specific guidance may be useful, to support case-by-case risk assessment;

4.Notes the conclusions of the Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Synthetic Biology that, given the current uncertainties regarding engineered gene drives, the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples and local communities might be warranted when considering the possible release of organisms containing engineered gene drives that may impact their traditional knowledge, innovation, practices, livelihood and use of land and water;

5. Calls for broad international cooperation, knowledge sharing and capacity-building to support, inter alia, Parties in assessing the potential adverse effects on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity from [living modified organisms produced through genome editing,] living modified organisms containing engineered gene drives and living modified fish, taking into account risks to human health, the value of biodiversity to indigenous peoples and local communities, and relevant experiences of individual countries in performing risk assessment of such organisms in accordance with annex III of the Cartagena Protocol;

The concerns of the CBD and the warnings of scientists have been entirely ignored by the agricultural biotechnology corporations and by the inter-connected funding organisations and research groups engaged in synthetic biology. As the report, ‘Forcing The Farm’, has said, multimillion-dollar grants for gene drive development have been given by Gates Foundation, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, the Open Philanthropy Institute, the Wellcome Trust and the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. These include generous allowances for what is called ‘public message testing’ and ‘public engagement exercises’ – making GDOs sound beneficial to society and glossing over the dangers – and lobbying of governments and policy-makers.

What is particularly worrying for us in India is the role of the Tata Trusts in financing research on GDOs. In 2016 October an American university, the University of California San Diego, received a US$70 million commitment from the Tata Trusts (which now is the umbrella organisation for what earlier were the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, the Sir Ratan Tata Trust and the Tata Education and Development Trust, and in terms of funding capacity is probably the largest in India) to establish the Tata Institute for Active Genetics and Society (TIAGS).

This new institute is described as a collaborative partnership between the university and research operations in India. A university press release had said: “UC San Diego, which will be home to the lead unit of the institute (TIAGS-UC San Diego), will receive US$35 million in funding, while the remainder of the committed funds is anticipated to support a complementary research enterprise in India (TIAGS-India).”

India is a signatory to the Cartagena Protocol of the Convention on Biological Diversity (signed 23/01/2001, ratified 17/01/2003, entered into force 11/09/2003) and its reporting to the Protocol on risk assessments of GMOs (which have officially not been used on food crops) has been worse than desultory – the five risk assessments submitted by India are all in 2012 for Bt cotton hybrids.

The shameful co-option of the statutory Genetic Engineering Approval Committee by India’s biotech companies, which was fully revealed in 2016 during the furore over the Committee’s bid to have GM mustard approved, has shown that the entire biosafety assessment process in India and its ability to actually protect our environment and citizens’ health from the profoundly menacing risks of biotechnology, is compromised.

The Gates Foundation, which has graduated from influencing central and state government policy in health and agriculture to becoming an implementing agency, and which has invested heavily in synthetic biotechnology and GDOs (such as ‘Target Malaria’, which uses gene drives against mosquitoes) is now collaborating with the Tata Trusts in health, nutrition and crop cultivation together with the American aid agency USaid and other foundations that claim philanthropic intentions. The risks to our agro-ecological methods, our local crop cultivation knowledge, our food and our public healthcare system have now become far more threatening.

Unmasking the new food syndicate

An agency of the central government is serving as administrative cover for an inter-connected group of international donor agencies, multinational corporations, international policy and advocacy groups, Indian industries and Indian non-government organisations, all bent on bringing the next wave of industrialisation to food and its sales.

The FSSAI communication to consumers highlights the look, texture, weight and size of vegetables. Good organic produce however is never uniform and is frequently ‘blemished’, which the FSSAI warns against buying.

This next wave of industrial food is based on existing and new genetic engineering and manipulation technologies, none of which there is adequate regulation for (nor, for some of these technologies, even recognition of). The justification created for claiming these technologies are needed is the shift from ‘hunger’ to the successors of ‘malnutrition’ which are: ‘hidden hunger’ and ‘micronutrient deficiency’. This shift is seen as having the potential to open up a vast and very lucrative new area of the food sector.

Because of the growing (slowly but steadily) tendency of consumers towards organically grown staple food crops and horticulture, and because of the growing opposition to genetically modified seed and food, the food industry in India is following a new strategy through this central government agency. The strategy includes:

1. Defining what ‘safe’ food is and defining what ‘nutrition’ is.

2. Strengthening and deepening the consumer markets for industrially grown and controlled crops from which processed and packaged food products are manufactured.

3. Protecting the businesses of Indian food (and beverage) companies and foreign food MNCs through legislation.

4. Consolidating the ‘back end’ of industrial retail and processed food – which is the interest of the agricultural biotechnology (agbiotech) corporations, the fertiliser and pesticides companies, the farming machinery industry, the food processing machinery industry, the food logistics sector.

5. Facilitating the further integration in India of the food and pharmaceutical industries through the promotion of food ‘fortification’ and food ‘supplements’.

Buy milk pasteurised, buy it packaged and buy it sealed says FSSAI. Milk is considered by the FSSAI’s international collaborators and local ‘nutrition coalitions’ to be the ideal medium for food ‘fortification’. Using what material? There are no answers.

The agency that has taken the responsibility for seeing this strategy through is the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI). It was established under the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 (No.34 of 2006). The FSSAI is described as having been “created for laying down science based standards for articles of food and to regulate their manufacture, storage, distribution, sale and import to ensure availability of safe and wholesome food for human consumption”.

The 2006 Act subsumed central acts like the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act 1954, Fruit Products Order 1955, and the Meat Food Products Order 1973. Other legislations like the Vegetable Oil Products (Control) Order 1947, Edible Oils Packaging (Regulation) Order 1988, Solvent Extracted Oil, De-Oiled Meal and Edible Flour (Control) Order 1967, Milk and Milk Products Order 1992 were repealed when the Food Safety and Standards Act 2006 commenced.

It is during the last two years in particular that the FSSAI has become very much more visible and active. This heightened visibility is a result of the FSSAI using the powers it has directly through the 2006 Act, but also because of its widening alliances with the food and beverages industry, with the dairy and milk products industry and with the global ‘nutrition’ consortia.

Edible oils must be packaged says FSSAI. The oil ‘ghani’ is scarcely seen nowadays, but its produce was fresher and gave households more confidence about the purity of the produce than blended oils can. Edible oils from GM oilseeds or GM vegetable oil sources are being imported with no safety oversight whatsoever, but FSSAI’s insistence that packaged edible oil is ‘safe’ discriminates against oil pressed at small scale from local oilseeds that may be entirely organic.

Today the FSSAI is very close to becoming a single reference point for all matters relating to food safety and standards, and is also very close to becoming the most important arbiter of what is considered ‘nutrition’ and what is considered ‘safe food’ in India. Because of the growth in recent years of the processed and packaged food industry (not the same as agriculture, horticulture, collection of forest products, inland and coastal small fisheries) the importance of a single reference point agency increases even more.

The largest formal industry associations – CII, Assocham and FICCI – estimate that in 2017 the retail or store value of packaged and processed foods (and beverages) was about 2,048,000 crore rupees (about US$ 320 billion) in 2016. This enormous estimate is thought by the industry to be able to rise much more to around 3,400,000 crore rupees (about US$ 540 billion) by 2021-22 provided of course changes are made in regulation, called ‘ease of doing business’ (the calamitous benchmark of the World Bank). The FSSAI is to be seen as a critical part of the overall apparatus to reach this gigantic sum in the next five or six years.

It is entirely possible if the FSSAI and its accomplice government agencies and ministries are permitted by us to get away with it. The same industry associations (interest clubs of companies and investors) say that the FMCG (fast moving consumer goods) sector in India has grown in rupee terms at an average of about 11% a year for the last decade and that four out of every 10 rupees spent on FMCGs are spent on food and beverages.

With practically no remaining restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) in the food and retail sector, and with the former Foreign Investment Promotion Board (under the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance) being replaced as an ‘ease of doing business’ change with the Foreign Investment Facilitation Portal (under the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Ministry of Commerce and Industry) the central government has done its bit to level – dangerously for both consumer health and for environmental well-being – the playing field.

For cereals and pulses too the FSSAI wants consumers to buy packaged, uniformly sized and fortified produce. The don’ts are fair but the dos only fulfil the agbiotech-pharma agenda.

The web of inter-connections that together exert great power over the food industry – and because of it over agriculture, horticulture, forestry products and fisheries – can be seen in how the FSSAI is set up and which agencies it advises. Its administrative ministry is the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The FSSAI works closely with the Ministry of Women and Child Development (its object being the Integrated Child Development Services, ICDS, which provides food, pre-school education, and primary healthcare to children under 6 years of age and their mothers), with the Department of School Education and Literacy of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (its object being the Mid-Day Meal Scheme).

The FSSAI relies on the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (Ministry of Commerce and Industry) to bring in (through the FDI route) or encourage private sector units that will prepare and deliver the material for food ‘fortification’ and food ‘supplements’. It coordinates with the Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries (Ministry of Agriculture) concerning the dairy industry – working directly with the National Dairy Development Board to ‘fortify’ milk. It synchronises its rules and regulations with the Ministry of Food Processing Industries, which is the single point of reference for an industry that has become gigantic.

Frozen foods are energy sinks and are the very antithesis of healthy meal ingredients. But FSSAI has a place for them in its advice to consumers.

Furthermore the FSSAI works in tandem with the Department of Biotechnology (Ministry of Science and Technology) and the Department of Health Research (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) in a joint effort to bring in and to develop biotechnology, genetic engineering and gene modification, and to find ways to publicise justifications (contrary to the great mass of scientific study that show GMOs to be harmful to humans, animals, soil and insects) for the use of these technologies and methods.

Thus although the FSSAI is considered by the Union Government of India to be an agency that has replaced multi-level, multi-departmental areas of control to a single line of command, just like the Foreign Investment Facilitation Portal or the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, these are agencies which do their work in concert, and that concert is played to the tune of the global agbiotech industry, the global food retailers, the e-commerce merchants and all their Indian corporate partners, subsidiaries and otherwise serfs.

Where genetically modified seed and crop, genetic engineering and gene manipulation in food ingredients and therefore food products are concerned, the FSSAI adopts the principle of lying low and saying nothing. In this its behaviour is consistent with that of the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC, under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, but over which the Department of Biotechnology has controlling influence) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (responsible for the formulation, coordination and promotion of biomedical research and which is administered by the Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare), both of which lie lower and say even less.

Even condiments and spices are passed by FSSAI as good to consume provided they are packed, packaged and sealed. In this way, the agency is preparing the ground for outlawing non-packaged, freshly ground and prepared foods and spices.

Such incoherence may partly explain why while the FSSAI collaborates with the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (which is under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry) towards its idea of ‘safe food’ and ‘nutrition’, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (also under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry) was asked by the Ministry of Environment to stop imports of GM soybean for food or feed without the approval of the GEAC.

The Coalition for a GM-free India has noted a string of imports of agricultural produce which should have been halted at the sea ports of entry and tested for whether they were GM/GE. The FSSAI has inspection sites at 21 locations including six sea ports. But the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) tested seed samples in Gujarat and found them to be genetically modified, while the Soybean Processors’ Association of India has raised serious concerns about the alleged import of GM soybean and farmers in Maharashtra complained about GM soyabean being cultivated for the last three years in Yavatmal.

There can be no excuse of any kind for these imports having taken place (and these are only the ones we have learnt about – seeds for planting can be imported via airfrieght at any international air cargo terminal in India). Till today, the Department of Consumer Affairs (Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution) has a well-publicised programme and campaign of consumer awareness – on such matters as maximum retail price, expiry date of food products, batch number and correct weight – but not on whether a food product has ingredients from GM crop and why it is important for a consumer to know this.

This is deliberately withholding information from consumers about food and food products that government agencies are certifying and permitting to be sold. While for organic foods there is a new regulation requiring quality assurance and traceability – under the Food Safety and Standards (Organic Foods) Regulations, 2017 – which attest to a product’s ‘organic status’ and its ‘organic integrity’, there is none whatsoever for products that have a GM ingredient.

“Essential nutrients”, “daily requirement”, “fight infections”, “strong and healthy”. The FSSAI uses the marketing gibberish of the infant and baby foods industry to daze consumers into believing that food ‘fortification’ is essential.

Under its ‘Safe and Nutritious Food’ programme, the FSSAI seeks to direct home consumers and institutional buyers of food products (such as company staff canteens) in all manner of standards relating to fresh, processed and packaged foods, edible oils, dairy products, meats and beverages. The FSSAI talks about standards for goat and sheep milk, chhana and paneer, whey cheese, cheese in brine, dairy permeate powder, refined vegetable oil, synthetic syrup and sharbat, coconut milk and coconut cream, wheat bran, non-fermented soybean products, processing aides for use in various food categories, limits for heavy metals, standards relating to pulses, millet, cornflakes, degermed maize, formulated supplements for children, honey, beeswax, additives in various food categories, tolerance limits of antibiotic and pharmacologically active substances.

But not a word about GMOs, over which we have had scarcely any regulation, and none at all about synthetic biology (also known as GMOs 2.0), which are not even close to being recognised as needing immediate regulation in India. Both generations of GMO survive by inventing and exaggerating claims of experimental science whose human, toxicological and environmental safety has not been studied thoroughly, by an absence of labelling to stringencies that are demanded of organic produce, by putting industry in control of food systems, by threatening biodiversity.

Some examples from elsewhere in the world are ‘probiotic yoghurt’ made out of engineered bacteria and other microorganisms which are intended to change bacteria inhabiting the human digestive tract, ‘gene sprays’ that can be sprayed directly onto crops in the feld to manipulate the genetics of pests and the terrible ‘gene drives’ which permanently ‘drive’ a genetic trait through a species to change the entire population forever by making it dependent on chemicals or to go extinct.

Warnings about allergies and additives. Why not about GM ingredients?

The FSSAI and its host ministry, the GEAC and its host ministry, every administrative apparatus of the Union Government and of the state governments are silent on this matter. They are just as silent on the question: of what materials are these so-called ‘fortification’ made?

The international donor agencies working with the FSSAI and being consulted by the agency on ‘safe food’, ‘nutrition’ and food fortification are the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, the Coalition for Food and Nutrition Security, the Food Fortification Initiative, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, the Iodine Global Network, Nutrition International, PATH, the Tata Trusts, UNICEF, the World Food Programme, the World Health Organisation and the World Bank. Each has an agenda that goes far beyond ‘food safety’. One or more of them undoubtedly has the answer.

All the conditions that are pointed to (wasting, stunting, chronic under-nutrition, anaemia) as needing remedies from food ‘fortification’ and ‘supplements’ can be easily remedied through more sensible crop cultivation choices and diets that are agro-ecologically and culturally sound. But food has long been a means of control, and this is the work that FSSAI does beyond and behind the ‘safety’ and ‘standards’ part of its mandate.

The struggle for the soul of food

There is food. There is no food. There is no contradiction in there being food and not-food at the same time.

But the not-food is not ‘no food’, it is primary crop that has been passed to food industry, instead of directly to households, and in that industry it is converted into a raw material that is entirely different from the cereals, vegetables, pulses and fruit forms that we consider food and which farmers grow.

That conversion is the food industry, and the demands of that conversion include the use of ‘high-response’ crop varieties, livestock and aquatic breeds, enormous doses of synthetic agro-chemicals and the flattening of ecosystems.

The food industry makes plants grow by applying pesticides and herbicides that sterilise all other life, takes those grown plants and reduces them to components, re-mixes and alters those components, infuses them with deadly formulations of chemicals so that they withstand the treatment of the supply and retail chain, packages them and sells them as ‘food’. This is the not-food that a majority of households in countries now eat.

The industrial food model is predicated on waste, on a false economy of surplus production of commodities rather than on the basis of ecological sustainability, on a biological science that has hideously distorted the rhythms of life.

In the last few weeks, several incisive new reports describe the problems with the industrial food model, and I have drawn quotes from four here. These are not the first. But the conditions they now describe for an old malady are not what we have seen before.

There is a fifth, which I call a pseudo-report. It describes the problems differently, as if they were disconnected from the source of the problems which the other four reports correctly identify. The FAO State Of Food And Agriculture 2017 report refuses to acknowledge the macro-economic, corporate science and finance capital causes for the problems.

Here are the summaries, with links:

Whereas historically the organisations’ proposal for agrarian reform referred particularly to land distribution and to access to productive resources, such as credit, financing, support for marketing of products, amongst others, the integral or genuine agrarian reform is based on the defence and the reconstruction of territory as a whole, within the framework of Food Sovereignty. The broadening of the object of agrarian reform, from land to territory also broadens the concept of the agrarian reform itself.

Whereas historically the organisations’ proposal for agrarian reform referred particularly to land distribution and to access to productive resources, such as credit, financing, support for marketing of products, amongst others, the integral or genuine agrarian reform is based on the defence and the reconstruction of territory as a whole, within the framework of Food Sovereignty. The broadening of the object of agrarian reform, from land to territory also broadens the concept of the agrarian reform itself.

“Therefore the contemporary proposal for integral agrarian reform does not only guarantee the democratisation of land, but also takes into consideration diverse aspects that allow families to have a decent life: water, the seas, mangroves and continental waters, seeds, biodiversity as

a whole, as well as market regulation and the end of land grabbing. Furthermore, it includes the strengthening of agro-ecological production as a form of production that is compatible with the cycles of nature and capable of halting climate change, maintaining biodiversity and reducing contamination.”

The Industrial Food Chain is a linear sequence of links running from production inputs to consumption outcomes. The first links in the Chain are crop and livestock genomics, followed by pesticides, veterinary medicines, fertilizers, and farm machinery. From there, the Chain moves on to transportation and storage, and then milling processing, and packaging. The final links in the Chain are wholesaling, retailing and ultimately delivery to homes or restaurants. In this text we use ‘industrial’ or ‘corporate’ to describe the Chain, and ‘commercial foods’ should undoubtedly be associated with the Chain. Just as peasants can’t be comprehended outside of their cultural and ecological context, the links in the Chain – from agro-inputs to food retailers – must be understood within the market economy. All the links in the Chain are connected within the financial and political system, including bankers, speculators, regulators and policymakers. The Chain controls the policy environment of the world’s most important resource – our food.”

The Industrial Food Chain is a linear sequence of links running from production inputs to consumption outcomes. The first links in the Chain are crop and livestock genomics, followed by pesticides, veterinary medicines, fertilizers, and farm machinery. From there, the Chain moves on to transportation and storage, and then milling processing, and packaging. The final links in the Chain are wholesaling, retailing and ultimately delivery to homes or restaurants. In this text we use ‘industrial’ or ‘corporate’ to describe the Chain, and ‘commercial foods’ should undoubtedly be associated with the Chain. Just as peasants can’t be comprehended outside of their cultural and ecological context, the links in the Chain – from agro-inputs to food retailers – must be understood within the market economy. All the links in the Chain are connected within the financial and political system, including bankers, speculators, regulators and policymakers. The Chain controls the policy environment of the world’s most important resource – our food.”

– From ‘Who Will Feed Us? The Peasant Food Web vs The Industrial Food Chain’, ETC Group, 2017

![]() A significant horizontal and vertical restructuring is underway across food systems. Rampant vertical integration is allowing companies to bring satellite data services, input provision, farm machinery and market information under one roof, transforming agriculture in the process. Mega-mergers come in the context of an already highly-consolidated agri-food industry, and are ushering in a series of structural shifts in food systems. Agrochemical companies are acquiring seed companies, paving the way for unprecedented consolidation of crop development pathways, and bringing control of farming inputs into fewer hands.

A significant horizontal and vertical restructuring is underway across food systems. Rampant vertical integration is allowing companies to bring satellite data services, input provision, farm machinery and market information under one roof, transforming agriculture in the process. Mega-mergers come in the context of an already highly-consolidated agri-food industry, and are ushering in a series of structural shifts in food systems. Agrochemical companies are acquiring seed companies, paving the way for unprecedented consolidation of crop development pathways, and bringing control of farming inputs into fewer hands.

“The mineral-dependent and already highly concentrated fertilizer industry is seeking further integration on the back of industry overcapacity and a drop in prices; fertilizer firms are also moving to diversify and integrate their activities via hostile takeovers, joint ventures, and the buying and selling of of regional assets– with mixed results. Meanwhile, livestock and fish breeders, and animal pharmaceutical firms, are pursuing deeper integration with each other, and are fast becoming a one-stop shop for increasingly concentrated industrial livestock industry. Leading farm machinery companies – already possessing huge market shares – are looking to consolidate up- and down-stream, and are moving towards ownership of Big Data and artificial intelligence, furthering their control of farm-level genomic information and trending market data accessed through satellite imagery and robotics.”

![]() Power — to achieve visibility, frame narratives, set the terms of debate, and influence policy — is at the heart of the food–health nexus. Powerful actors, including private sector, governments, donors, and others with influence, sit at the heart of the food–health nexus, generating narratives, imperatives, and power relations that help to obscure its social and environmental fallout. Prevailing solutions leave the root causes of poor health unaddressed and reinforce existing social-health inequalities.

Power — to achieve visibility, frame narratives, set the terms of debate, and influence policy — is at the heart of the food–health nexus. Powerful actors, including private sector, governments, donors, and others with influence, sit at the heart of the food–health nexus, generating narratives, imperatives, and power relations that help to obscure its social and environmental fallout. Prevailing solutions leave the root causes of poor health unaddressed and reinforce existing social-health inequalities.

“These solutions, premised on further industrialization of food systems, grant an increasingly central role to those with the technological capacity and economies of scale to generate data, assess risks, and deliver key health fixes (e.g., biofortification, highly traceable and biosecure supply chains). The role of industrial food and farming systems in driving health risks (e.g., by perpetuating poverty and climate change) is left unaddressed. As well, those most affected by the health impacts in food systems (e.g., small-scale farmers in the Global South) become increasingly marginal in diagnosing the problems and identifying the solutions.”

– From ‘Unravelling the Food–Health Nexus: Addressing practices, political economy, and power

relations to build healthier food systems’, The Global Alliance for the Future of Food and IPES-Food, 2017

a) Industrialization, the main driver of past transformations, is not occurring in most countries of sub-Saharan Africa and is lagging in South Asia. People exiting low-productivity agriculture are moving mostly into low-productivity informal services, usually in urban areas. The benefits of this transformation have been very modest.

a) Industrialization, the main driver of past transformations, is not occurring in most countries of sub-Saharan Africa and is lagging in South Asia. People exiting low-productivity agriculture are moving mostly into low-productivity informal services, usually in urban areas. The benefits of this transformation have been very modest.

b) In the decades ahead, sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, will face large increases in its youth population and the challenge of finding them jobs. Workers exiting agriculture and unable to find jobs in the local non-farm economy must seek employment elsewhere, leading to seasonal or permanent migration.

c) The world’s 500 million smallholder farmers risk being left behind in structural and rural transformations. Many small scale producers will have to adjust to ongoing changes in “downstream” food value chains, where large-scale processors and retailers, who are taking centre stage, use contracts to coordinate supply and set strict standards to guarantee food quality and safety. Those requirements can marginalize smallholder farmers who are unable to adjust.

d) Urbanization, population increases and income growth are driving strong demand for food at a time when agriculture faces unprecedented natural-resource constraints and climate change. These increases have implications for agriculture and food systems – they need to adapt significantly to become more productive and diversified, while coping with unprecedented climate change and natural resource constraints.”

GM and its public sector servants in India

The facade of sophisticated science carries with it an appeal to the technocrats within our central government and major ministries, and to those in industry circles, with the apparently boundless production and yield vistas of biotechnology seeming to complement our successes in space applications, in information technology, in nuclear power and complementing the vision of GDP growth.

Framed by such science, the messages delivered by the biotech MNC negotiators and their compradors in local industry appear to be able to help us fulfil the most pressing national agendas: ensure that food production keeps pace with the needs of a growing and more demanding population, provide more crop per drop, deliver substantially higher yield per acre, certified and high-performing seeds will give farmers twice their income, consumers will benefit from standardised produce at low rates, crops will perform even in more arid conditions, the use of inputs will decrease, and the litany of promised marvels goes on.

Yet it is an all-round ignorance that has allowed such messages to take root and allowed their messengers to thrive in a country that has, in its National Gene Bank over 157,000 accessions of cereals (including 95,000 of paddy and 40,000 of wheat), over 56,000 accessions of millets (the true pearls of our semi-arid zones), over 58,000 accessions (an accession is a location-specific variety of a crop species) of pulses, over 57,000 of oilseeds (more than 10,000 of mustard), and over 25,000 of vegetables.

And even so the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources reminds us that while the number of cultivated plant species is “relatively small and seemingly insignificant”, nature in India has evolved an extraordinary genetic diversity in crop plants and their wild relatives which is responsible for every agro-ecological sub-region, and every climatic variation and soil type that may be found in such a sub-region, being well supplied with food.

With such a cornucopia, every single ‘framed by great science’ claim about a GM crop made by the biotech MNCs must fall immediately flat because we possess the crop diversity that can already deliver it. Without the crippling monopolies that underlie the science claim, for these monopolies and licensing traps are what not only drove desi cotton out when Bt cotton was introduced but it did so while destroying farming households.

Without the deadly risk of risk of genetic contamination and genetic pollution of a native crop (such as, GM mustard’s risk to the many varieties of native ‘sarson’). Without the flooding of soil with a poison, glufosinate, that is the herbicide Bayer-Monsanto will force the sale of together with its GM seed (‘Basta’ is Bayer’s herbicide that is analogous to Monsanto’s fatal Glyphosate, which is carcinogenic to humans and destroys other plant life – our farmers routinely intercrop up to three crop species, for example mustard with chana and wheat, as doing so stabilises income).

Whereas the veil of ignorance is slowly lifting, the immediate questions that should be asked by food grower and consumer alike – how safe is it for plants, soil, humans, animals, pollinating insects and birds? what are the intended consequences? what unintended consequences are being studied? – are still uncommon when the subject is crop and food. This is what has formed an ethical and social vacuum around food, which has been cunningly exploited by the biotech MNCs and indeed which India’s retail, processed and packaged foods industry have profited from too.

When in October 2016 our National Academy of Agricultural Sciences shamefully and brazenly assured the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change on the safety of GM mustard, it did so specifically “To allay the general public concerns”. What followed was outright lies, such as “herbicide is used in the process only in hybrid production plot”, “The normal activity of bees is not affected”, “GE Mustard provides yield advantage”, “no adverse effect on environment or human and animal health”. None of these statements was based on study.

India grows food enough to feed its population ten years hence. What affects such security – crop choices made at the level of a tehsil and balancing the demands on land in our 60 agro-ecological sub-zones and 94 river sub-basins – is still influenced by political position, the grip of the agricultural ‘inputs’ industry on farmers, economic pressures at the household level, and the seasonal cycle. In dealing with these influences, ethics, safety and social considerations are rarely if ever in the foreground. Yet India is a signatory to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and its Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, whose Article 17 requires countries to prevent or minimise the risks of unintentional transboundary movements of genetically engineered organisms.

Neither the Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC), in the case of GM mustard, nor the Department of Biotechnology, the Department of Science and Technology (whose Technology Information, Forecasting and Assessment Council in a 2016 report saw great promise in genetic engineering for India), the Ministries of Environment and Agriculture, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR, with its 64 specialised institutions, 15 national research centres, 13 directorates, six national bureaux and four deemed universities), the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) have mentioned ethics, consumer and environment safety, or social considerations when cheering GM.

This group of agencies and institutions which too often takes its cue from the west, particularly the USA (which has since the 1950s dangled visiting professorships and research partnerships before the dazzled eyes of our scientific community) may find it instructive to note that caution is expressed even by the proponents of genetic engineering technologies in the country that so inspires them. In 2016 a report on ‘Past Experience and Future Prospects’ by the Committee on Genetically Engineered Crops, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine of the USA, recognised that the public is sceptical about GE crops “because of concerns that many experiments and results have been conducted or influenced by the industries that are profiting from these crops” and recommended that “ultimately, however, decisions about how to govern new crops need to be made by societies”.

Practices and regulations need to be informed by accurate scientific information, but recent history makes clear that what is held up as unassailable ‘science’ is unfortunately rarely untainted by interests for whom neither environment nor human health matter.

[This is the second part of an article that was published by Swadeshi Patrika, the monthly journal of the Swadeshi Jagran Manch. Part one is here.]

How GM ‘science’ misled India

For the last decade, the reckoning of what agriculture is to India has been based on three kinds of measures. The one that has always taken precedence is the physical output. Whether or not in a crop year the country has produced about 100 million tonnes (mt) of rice, 90 mt of wheat, 40 mt of other cereals (labelled since the colonial era as ‘coarse’ although they are anything but, and these include ragi, jowar, bajra and maize), 20 mt of pulses, 30 mt of oilseeds, and that mountain of biomass we call sugarcane, about 350 mt, therewith about 35 million bales of cotton, and about 12 million bales of jute and mesta.

The second measure is that of the macro-economic interpretation of these enormous aggregates. This is described in terms of gross value added in the agriculture (and allied) sector, the contribution of this sector to the country’s gross domestic product, gross capital formation in the sector, the budgetary outlays and expenditures both central and state for the sector, public and private investment in the sector. These drab equations are of no use whatsoever to the kisans of our country but are the only dialect that the financial, business, trading and commodity industries take primary note of, both in India and outside, and so these ratios are scrutinised at the start and end of every sowing season for every major crop.

The third measure has to do mostly with the materials, which when applied by cultivating households (156 million rural households, of which 90 million are considered to be agricultural only) to the 138 million farm holdings that they till and nurture, maintains the second measure and delivers the first. This third measure consists of labour and loans, the costs and prices of what are called ‘inputs’ by which is meant commercial seed, fertiliser, pesticide, fuel, the use of machinery, and labour. It also includes the credit advanced to the farming households, the alacrity and good use to which this credit is put, insurance, and the myriad fees and payments that accompany the transformation of a kisan’s crop to assessed and assayed produce in a mandi.

It is the distilling of these three kinds of measures into what is now well known as ‘food security’ that has occupied central planners and with them the Ministries of Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Consumer Affairs (which runs the public distribution system), and Food Processing Industries. More recently, two new concerns have emerged. One is called ‘nutritional security’ and while it evokes in the consumer the idea which three generations ago was known as ‘the balanced diet’, has grave implications on the manner in which food crops are treated. The other is climate change and how it threatens to affect the average yields of our major food crops, pushing them down and bearing the potential to turn the fertile river valley of today into a barren tract tomorrow.

It is the distilling of these three kinds of measures into what is now well known as ‘food security’ that has occupied central planners and with them the Ministries of Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Consumer Affairs (which runs the public distribution system), and Food Processing Industries. More recently, two new concerns have emerged. One is called ‘nutritional security’ and while it evokes in the consumer the idea which three generations ago was known as ‘the balanced diet’, has grave implications on the manner in which food crops are treated. The other is climate change and how it threatens to affect the average yields of our major food crops, pushing them down and bearing the potential to turn the fertile river valley of today into a barren tract tomorrow.

These two new concerns, when added to the ever-present consideration about whether India has enough foodgrain to feed our 257 million (in 2017) households, are today exploited to give currency to the technological school of industrial agriculture and its most menacing method: genetically modified (GM) or engineered seed and crop. The proprietors of this method are foreign, overwhelmingly from USA and western Europe and the western bio-technology (or ‘synbio’, as it is now being called, a truncation of synthetic biology, which includes not only GM and GE but also the far more sinister gene editing and gene ‘drives’) network is held in place by the biggest seed- and biotech conglomerates, supported by research laboratories (both academic and private) that are amply funded through their governments, attended to by a constellation of high-technology equipment suppliers, endorsed by intergovernmental groupings such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), taken in partnership by the world’s largest commodities trading firms and grain dealers (and their associates in the commodities trading exchanges), and amplified by quasi-professional voices booming from hundreds of trade and news media outlets.

This huge and deep network generates scientific and faux-scientific material in lorry-loads, all of it being designed to bolster the claims of the GM seed and crop corporations and flood the academic journals (far too many of which are directly supported by or entirely compromised to the biotech MNCs) with ‘peer-reviewed evidence’. When the ‘science’ cudgel is wielded by the MNCs through their negotiators in New Delhi and state capitals, a twin cudgel is raised by the MNC’s host country: that of trade, trade tariffs, trade sanctions and trade barriers. This we have witnessed every time that India and the group of ‘developing nations’ attends a council, working group, or dispute settlement meeting of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The scientific veneer is sophisticated and well broadcast to the public (and to our industry), but the threats are medieval in manner and are scarcely reported.

[This is the first part of an article that was published by Swadeshi Patrika, the monthly journal of the Swadeshi Jagran Manch. Part two is here.]

A beginning to Monsanto’s end

Enough is enough. Just under a year from now, the Monsanto Tribunal will sit in Den Haag (The Hague), Holland, to assess allegations made all over the world against Monsanto, and to evaluate the damages caused by this transnational company.

Enough is enough. Just under a year from now, the Monsanto Tribunal will sit in Den Haag (The Hague), Holland, to assess allegations made all over the world against Monsanto, and to evaluate the damages caused by this transnational company.

The Tribunal will examine how and why Monsanto is able to ignore the human and environmental damage caused by its products and “maintain its devastating activities through a strategy of systemic concealment”. This it has done for years, the Tribunal has said in an opening announcement, by lobbying regulatory agencies and governments, by resorting to lying and corruption, by financing fraudulent scientific studies, by pressuring independent scientists, by manipulating the press and media. As we know in India, that is only a part of its bag of very dirty tricks; others are even more vile.

The history of this corporation – representative of a twisted industrial approach to crop, food, soil, water and biodiversity which we today collectively call ‘bio-technology’ – is constitutes a roster of impunities. Like its peers and its many smaller emulators, Monsanto promotes an agro-industrial model that is estimated to contribute a third of global greenhouse gas emitted by human activity, a lunatic model largely responsible for the depletion of soil and water resources on every continent, a model so utterly devoted to the deadly idea that finance and technology can subordinate nature that species extinction and declining biodiversity don’t matter to its agents, a model that has caused the displacement of millions of small farmers worldwide.

In this demonic pursuit Monsanto – like its peers, its emulators and as its promoters do in other fields of industry and finance – has committed crimes against the environment, and against ecological systems, so grave that they need to be termed ecocide. In order that the recognition of such crimes becomes possible, and that punishment and deterrence at planetary scale becomes possible, the Tribunal will rely on the ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’ adopted at the United Nations in 2011, and on the basis of the Rome Statue that created the International Criminal Court in The Hague in 2002. The objective is that Monsanto become criminally liable and prosecutable for crimes against the environment, or ecocide.

In this demonic pursuit Monsanto – like its peers, its emulators and as its promoters do in other fields of industry and finance – has committed crimes against the environment, and against ecological systems, so grave that they need to be termed ecocide. In order that the recognition of such crimes becomes possible, and that punishment and deterrence at planetary scale becomes possible, the Tribunal will rely on the ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’ adopted at the United Nations in 2011, and on the basis of the Rome Statue that created the International Criminal Court in The Hague in 2002. The objective is that Monsanto become criminally liable and prosecutable for crimes against the environment, or ecocide.

“Recognising ecocide as a crime is the only way to guarantee the right of humans to a healthy environment and the right of nature to be protected,” the Tribunal has said. Since the beginning of the 20th century Monsanto has developed a steady stream of highly toxic products which have permanently damaged the environment and caused illness or death for thousands of people. These products include:

* PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyl), one of the 12 Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP) that affect human and animal fertility.

* 2,4,5 T (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid), a dioxin-containing component of the defoliant, Agent Orange, which was used by the US Army during the Vietnam War and continues to cause birth defects and cancer.

* Lasso, an herbicide that is now banned in Europe.

* RoundUp, the most widely used herbicide in the world, and the source of the greatest health and environmental scandal in modern history. This toxic herbicide, designated a probable human carcinogen by the World Health Organization, is used in combination with genetically modified (GM) RoundUp Ready seeds in large-scale monocultures, primarily to produce soybeans, maize and rapeseed for animal feed and biofuels.

The Tribunal has: Corinne Lepage, a lawyer specialising in environmental issues, former environment minister and Member of tne European Parliament, Honorary President of the Independent Committee for Research and Information on Genetic Engineering (CRIIGEN); Olivier De Schutter, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Co-Chair of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food); Gilles-Éric Séralini, professor of molecular biology since 1991, researcher at the Fundamental and Applied Biology Institute (IBFA); Hans Rudolf Herren, President and CEO of the Millenium Institute and President and Founder of Biovision; Vandana Shiva, founder of Navdanya to protect the diversity and integrity of living resources especially native seed, the promotion of organic farming and fair trade; Arnaud Apoteker, from 2011 to 2015 in charge of the GMO campaign for the Greens/EFA group at the European Parliament; Valerie Cabanes, lawyer in international law with expertise in international humanitarian law and human rights law; Ronnie Cummins, International Director of the Organic Consumers Association (USA) and its Mexico affiliate, Via Organica; Andre Leu, President of IFOAM Organics International, the world umbrella body for the organic sector which has around 800 member organisations in 125 countries; and Marie-Monique Robin, writer of the documentary (and book) ‘The World According Monsanto’, which has been broadcast on 50 international television stations, and translated into 22 languages.

The Tribunal has: Corinne Lepage, a lawyer specialising in environmental issues, former environment minister and Member of tne European Parliament, Honorary President of the Independent Committee for Research and Information on Genetic Engineering (CRIIGEN); Olivier De Schutter, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Co-Chair of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food); Gilles-Éric Séralini, professor of molecular biology since 1991, researcher at the Fundamental and Applied Biology Institute (IBFA); Hans Rudolf Herren, President and CEO of the Millenium Institute and President and Founder of Biovision; Vandana Shiva, founder of Navdanya to protect the diversity and integrity of living resources especially native seed, the promotion of organic farming and fair trade; Arnaud Apoteker, from 2011 to 2015 in charge of the GMO campaign for the Greens/EFA group at the European Parliament; Valerie Cabanes, lawyer in international law with expertise in international humanitarian law and human rights law; Ronnie Cummins, International Director of the Organic Consumers Association (USA) and its Mexico affiliate, Via Organica; Andre Leu, President of IFOAM Organics International, the world umbrella body for the organic sector which has around 800 member organisations in 125 countries; and Marie-Monique Robin, writer of the documentary (and book) ‘The World According Monsanto’, which has been broadcast on 50 international television stations, and translated into 22 languages.

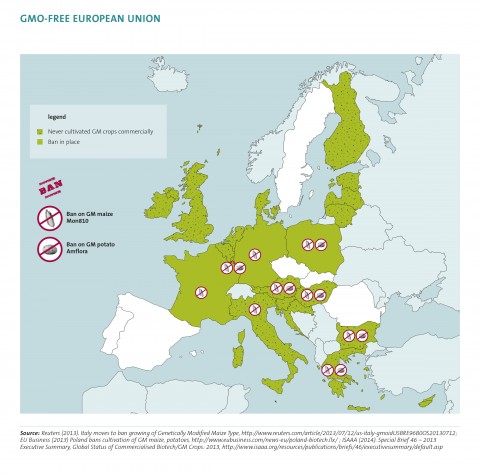

In Europe, a vote for the right to keep GM out

The ‘no’ vote has given the European Parliament an excellent chance to improve EU legislation and give member states genuine tools to protect the environment and promote genuinely sustainable farming. Image: Friends of the Earth Europe

Members of the European Parliament have defeated a European Commission proposal to prevent member states from banning genetically modified crops on health and/or environmental grounds. The result of this vote means that national bans on GM crops, for environmental or health reasons, are allowed even if the EU approves genetically modified (GM) crops for cultivation.

The European Food and Safety Authority had approved GM for use in the EU, but a number of countries opposed to GM (like France) demanded the right to block crops under a principle known as ‘subsidiarity’, or devolution to individual countries.

The Greens/European Free Alliance has said that the vote by Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) strengthens the grounds on which EU member countries could opt out from GMO authorisations under the proposed new system.

In a statement the Greens/European Free Alliance said: “No must mean no: countries wanting to opt out of GM authorisations must have a totally legally watertight framework for doing so. MEPs have also voted for the inclusion of mandatory measures to prevent the contamination of non-GM crops, with the myriad of issues this raises. The committee also rejected a proposal from EU governments, which would have obliged member states to directly request that corporations take them out of the scope of their GMO applications, before being allowed to opt out.”

However, the Greens are still very concerned that the new opt out scheme is a slippery slope for easing EU GMO authorisations and does not fundamentally change the flawed EU approval process in itself. Organisations, scientists, academics, political fronts and citizens’ alliances who do not want GM crop or food in their regions and countries nonetheless see an urgent need to reform the EU’s GMO authorisation process. On 03 November 2014, signatures from more than 160,000 European citizens were presented to the vice-chair of the Environment Committee calling on him to close these loopholes.

Eight EU countries have banned the cultivation of GM crops (others have not commercially grown such crops). The only crop permitted, Monsanto’s GM maize, is restricted to some areas of Spain and four other countries. Image: Friends of the Earth Europe

Currently, authorisations proceed in spite of flawed risk assessments and the consistent opposition of a majority of EU member states in Council and, importantly, a clear majority of EU citizens. They have warned against a trade-off of easier EU authorisations against easier national bans. For the EU, the next step must be an EU-wide total ban and total rejection of GM crop, food, seed and technology in all its forms, otherwise the new proposal for EU GMO approvals is a Trojan horse which risks finally opening the door to GMOs despite citizens’ opposition, and which will keep open the route for GM/biotech companies to appeal against such bans (a route that European Greens and the many groups that have rejected GM want to shut once and for all).

Such a next step – which is the logical and moral next step for the European Parliament to take – is necessary to overturn completely the current arrangement which treats biotech companies and corporations at the same level as governments. Under the arrangement that existed till now (the ramifications of this week’s ‘no’ vote must still be examined) an EU member country which does not want GMO to be grown on its territory must request the biotech company (through the European Commission) that its territory be excluded from the geographical scope of the EU authorisation. Only if the country has applied for a ‘territorial exemption’ and been refused by the company is the country allowed to then implement a ban on GMO on its territory.

How utterly contemptuous of a country’s sovereign rights this arrangement was, and how it found its way into procedure illustrates dramatically the power and influence that the GM and biotech industry has come to wield in the EU – the decision of the geographical scope of an EU authorisation gave more weight to biotech/GM companies than to governments!

In the debate about GM crops, the argument that the biotech industry and their supporters always fall back on is that whether we like it or not, we are going to need them to feed the world. Genetic modification has, they assure us, the potential to produce crops with all sorts of wonderful traits: tolerance of drought, cold, salinity and flooding, resistance to insect pests, extra nutritional value, and more.