Posts Tagged ‘2014’

The fuel favour year for India

The US$ per barrel (red line) and the rupee-dollar exchange rate (green line) are plotted to the left scale. The rupee per barrel (blue line) is plotted to the right scale. I have used data from the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas – the global crude oil price of the ‘Indian Basket’ in US$ per barrel.

It started in early August, the extraordinary slide in petroleum prices. Until then, the international crude oil price of the ‘Indian Basket’ (of crude oils, as it is called) had swung between US$ 110 and US$ 105 per barrel.

The rupee-dollar exchange rate, and the effective price of a barrel of crude oil in Indian rupees (both measures also appear on this chart), fluctuated but little for most of the first half of 2014. In early June 2014, the rupee-dollar rate turned around from 59 and has been rising since, while in early July the rupee price per barrel descended from its plateau of 6,300-6,600 and has been dropping since.

The cost of oil-derived energy has had a number of effects upon our everyday lives in the second half of 2014. It has helped the new NDA-BJP government during its first year by dampening overall inflation (the consumer price index) and particularly food price inflation. This has been particularly fortunate for the NDA-BJP government as the deficient monsoon of 2014 has meant a drop in the production of food staples, and market forces being what they are, food price inflation especially would have been well into the 13%-14% range (last quarter 2014 compared with last quarter 2013).

Galloping consumer price inflation has been forestalled by the plunging price of crude oil. The data I have used for this startling chart is courtesy the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC) of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas which computes several times a week the “global crude oil price of Indian Basket in US$ per bbl” – which means the average price we pay per barrel for the various kinds of crude oil we purchase.

Galloping consumer price inflation has been forestalled by the plunging price of crude oil. The data I have used for this startling chart is courtesy the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC) of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas which computes several times a week the “global crude oil price of Indian Basket in US$ per bbl” – which means the average price we pay per barrel for the various kinds of crude oil we purchase.

A barrel of crude oil is 42 gallons or around 159 litres. This crude, when refined, is turned into diesel, petrol, lighter fuels, feedstock for the manufacture of various plastics, and other products. Typically, up to 70% of the oil we buy is converted into diesel and petrol (and carbon from all those exhaust pipes). Also typically, a barrel of crude oil (which is an extremely dense form of packaged energy) contains around 5.8 million BTUs (British thermal units). More familiar to us is the kilowatt hour (or kWh) and these 5.8 million BTUs are about 1,700 kWh – at current national average rates of per head electricity consumption this is worth about 26 months of electricity!

From early August till the end of December the price we paid for a barrel of crude has dropped from around US$ 103 to US$ 54 and correspondingly (factoring in the rupee-dollar exchange rate) the rupee price of a barrel of crude has dropped from 6,300 to around 3,500. Put another way, the INR 6,300 we paid in early August for 5.8 million BTU could buy, in mid-October 7.1 million BTU and by end-December, 10.4 million BTU.

Most of us tend not to be profligate with energy (our electricity comes mainly from the burning of coal, but the sale of automobiles has continued at a steady pace, or so the industry tells us). The question is whether this windfall energy saving (in terms of petroleum energy units per rupee) has been well used by the sector that can spread the benefit the most – agriculture and food. It will take another three months to judge, and we will keep a wary eye for the next quarter on the Indian crude oil Basket.

An erratic monsoon with late spikes

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions near drought in many districts, but for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from individual districts and not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’.

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions near drought in many districts, but for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from individual districts and not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’.

The weekly rainfall variation table for Maharashtra’s districts. The period of the last week of August and the first two weeks of September is the only period during which these districts received rainfall at or above normal. But overall, the second deficient category, coloured light rose, dominates (this table uses my modified monsoon measure methodology, see text for link)

This revealing chart tells some of that tale. It shows that for the first six weeks of monsoon 2014, most districts recorded rain below their normals for those weeks.

The lines are percentile lines; they tell us what percent of districts recorded how much rainfall in a monsoon week relative to their normals for that week. This chart does not show how much rain – it shows distance away from a weekly normal for districts.

The left scale is a percentage – higher percentages indicate how much above normal districts recorded their rainfall, negative numbers show us how much below normal their rainfall was.

The dates (the bottom scale) are for weeks ending on that date for which ‘normals’ and departures from normal were recorded. The P_01 to P_09 lines are the percentiles (10th to 90th) of districts in every week.

The typical IMD map of ‘normal’ rainfall measured by the meteorological sub-divisions. The detailed weekly tables give us a very different picture.

The district weekly normal is an important measure for matters like sowing of crop and issuing water rationing instructions in talukas and blocks. In the week ending 23 July for example, we see that the 60th percentile line spiked above normal, and this means that in that week only four out of ten districts all over India received the amount of rain it should have based on the average of the last 50 years.

The districts overview chart is distilled from the detailed weekly tables I have assembled (see the image of the Maharashtra table). For the whole country, what the districts tell us about the monsoon so far is a very much more detailed and insightful tale than the typical offering by the Meteorological Department (see India sub-divisional map). These weekly district tables are coded using my modified monsoon methodology, geared towards aiding decisions for local administrations especially for prolonged arid conditions leading to drought.

Where are Bharat’s local leafy greens in this chart?

Here is the list of the principal vegetables grown, according to the third advance estimates for 2013-14 (the agricultural year is July to June) for horticultural crops. The figures are from the usual source, the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture. The quantities are in million tons. Where’s the vegetable diversity? Where are the leafy greens? Are they included in that bland circle called ‘others’? The DAC won’t/can’t tell us.

Here is the list of the principal vegetables grown, according to the third advance estimates for 2013-14 (the agricultural year is July to June) for horticultural crops. The figures are from the usual source, the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture. The quantities are in million tons. Where’s the vegetable diversity? Where are the leafy greens? Are they included in that bland circle called ‘others’? The DAC won’t/can’t tell us.

This is an enlightening comment a reader of Resources Research. Neville said:

“We moved to Goa 5 years ago from California. First thing that shocked us was the (low) quality and diversity of greens and other vegetables here. Most farmers here have stopped growing due to the soaring price of land, so veggies are trucked in from Belgaum where there doesn’t seem to be any oversight or regulations. For example, we stopped buying spinach and other leafy greens as they reek of DDT 90% of the time. The average person doesn’t seem to notice / care. There is a healthcare crisis here in Goa – soaring rates of cancer and stroke and I am convinced it is due to the bad quality of food and the rampant burning of plastic waste. We now grow our own veggies or buy from small-time villagers. Sad state of affairs indeed.”

The numbers are: Beans 1.213; Bitter gourd 0.971; Bottle gourd 2.192; Brinjal 13.842; Cabbage 9.109; Capsicum 0.156; Carrot 1.19; Cauliflower 8.585; Cucumber 0.69; Muskmelon 0.702; Okra/Ladyfinger 6.461; Onion 19.769; Peas 4.165; Potato 44.306; Radish 2.561; Sitaphal/Pumpkin 0.356; Sweet Potato 1.126; Tapioca 7.778; Tomato 19.193; Watermelon 1.827; Others 21.953.

Why IMD’s rain math doesn’t add up

Each blue bar represents the actual rainfall recorded by a district as a percentage of its normal. There are 614 district recordings in this chart.. The red dotted line is the 100% mark, and many of the bars end below, or way below, this mark. This is the district-level view of cumulative rainfall over eight rain weeks using the IMD’s own data.

Over eight weeks of recorded monsoon rain, the district-level data available with the India Meteorological Department (IMD) portrays a picture that is very different from its ‘national’ and ‘regional’ advice about the strength and consistency of rainfall.

In its first weekly briefing on the monsoon of August 2014, IMD said: “For the country as a whole, cumulative rainfall during this year’s monsoon (01 June to 30 July 2014) has so far upto 30 July been 23% below the Long Period Average.” Out of 36 meteorological sub-divisions, said the IMD, the rainfall has been normal over 15 and deficient over 21 sub-divisions.

However, here is a far more realistic reading of the monsoon season so far, from the IMD’s own data. For the 614 individual readings from districts that have regular rainfall readings, we have the following: 86 districts have registered scanty rainfall (-99% to -60%); 281 districts have registered deficient rainfall (-59% to -20%); 200 districts have registered normal rainfall (-19% to +19%); and 47 districts have registered excess rainfall (+20% and more).

What this means, and the chart I have provided to illustrate the 614 individual values leaves us in no doubt, is that 367 out of 614 districts have had meagre rain for eight weeks. This also means that over eight weeks where there should have been rainfall that – as the IMD predicted in early June – would be around 95% of the ‘long period average’, instead three out of five districts have had less than 80% of their usual quota.

An India economical with monsoon truths

Monsoon measures for six weeks. A few more districts reporting the revised normal, but the deficient-2 category still has too many districts, and so does excess-2. And why so many ‘no data’ (many from the north-east)?

When a politician and a bureaucrat get together to supply punditry on the monsoon, the outcome is directionless confusion. There is no reason for our shared knowledge on monsoon 2014 to be reduced to a few boilerplate paragraphs and a couple of amateurish maps and charts, not with the equipment and scientific personnel the Republic of India has invested in so that we read the rain better. But Jitendra Singh, the Minister of State who is in charge of Science, Technology and Earth Sciences, and Laxman Singh Rathore, the Director General of the India Meteorological Department, have not progressed beyond the era of cyclostyled obfuscation.

The Press Information Bureau reported Singh as saying that there has been “significant increase in the monsoon during the last one week beginning from 13th July, and the seven days between last Sunday and this Sunday have recorded 11 percent increase in the monsoon country-wide”. Following suit, Rathore said: “The monsoon deficit has come down by 12 per cent and the overall deficit stands at around 31 per cent. This will bring in much needed relief to the farmers and solve the water issues.”

Coming from senior administrators, such fuzzy distraction cannot be tolerated. The Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting must cease (desist, stop, halt – do it now) the use of a ‘national’ rainfall average to describe the progress of monsoon 2014. This is a measure that has no meaning whatsoever for cultivators in any of our agro-ecological zones, and has no meaning for any individual taluka or tehsil in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions. What we need to see urgently adopted is a realistic overview that numerically and graphically explains the situation, at as granular a level as possible.

When that does not happen, news media and information sources struggle to make sense of monsoon and climate and their reporting becomes dangerously misleading – consider “Late monsoon starts Indian farmer’s ‘journey to hell’ “; “Why the monsoon numbers hide reality” (this report is an attempt to point out the problem); “Monsoon deficit has come down to 31 per cent, no need to be ‘alarmist’: Met office”; “Satisfactory rainfall may wash away monsoon deficit”.

When that does not happen, news media and information sources struggle to make sense of monsoon and climate and their reporting becomes dangerously misleading – consider “Late monsoon starts Indian farmer’s ‘journey to hell’ “; “Why the monsoon numbers hide reality” (this report is an attempt to point out the problem); “Monsoon deficit has come down to 31 per cent, no need to be ‘alarmist’: Met office”; “Satisfactory rainfall may wash away monsoon deficit”.

Using a revised categorisation of rainfall sufficiency levels (my method and the reasoning for it use is available here) we find that for the fifth and sixth weeks of monsoon, there has been a small improvement which does not lower the high likelihood of drought conditions becoming prevalent in districts and scarcity of water for our settlements – Messers Singh and Rathore please note (or visit the Indian Climate Portal Monsoon 2014 page which is an active repository of reportage, views, commentary and original data analysis on our monsoon).

The fifth monsoon week is 03 to 09 July 2014 and the sixth monsoon week is 10 to 16 July 2014. There has been a small addition to the revised normal rainfall category (-5% to +5%), rising from 18 districts recording normal rainfall in the 4th week to 22 in the 5th and 28 in the 6th. There has also been an improvement in the number of districts recording deficit-2 levels of rainfall (-21% and more) with 437 in the 4th week, 411 in the 5th week and 385 in the 6th week. For the remainder of July the likelihood of more rainfall in the districts that have recorded normal or excess-1 (+6% to +20%) is small, according to the available forecasts, and this means that monsoon 2014 will begin August with far fewer districts registering normal rainfall than they should at this stage.

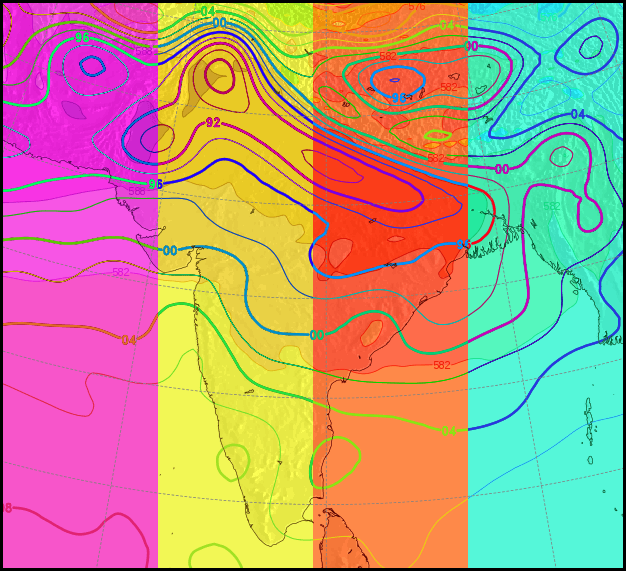

The NOAA map of the land and sea percentiles. Note the warm water south of India and to the east of the Philippines.

With many sowing cycles beginning belatedly between now and the end of July, the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Water Resources are advised to work together (why aren’t they doing so already – or at least mandating ICAR institutes to supply them with analysis which they must absorb jointly?) to understand the impacts of regional, tropical and global climate trends that affect the Indian summer monsoon.

There is good reason to. According to NOAA, for 2014 June land and ocean surface temperatures jumped 0.72 Celsius above the 20th century average. These new records were pushed upwards by a broad warming of the ocean surface, and not only by an Equatorial Pacific whose waters are approaching the warmth usually seen during an El Nino. NOAA has said there was “extreme warming of almost every major world ocean zone” which warmed local air masses and had a far-reaching impact on global climate, “likely delaying the Indian monsoon”.

Quiet preparations for scarce water, smaller harvests

State and district officials will have to turn forms like this (the drought management information system) into preparation on the ground and in each panchayat.

The Ministry of Agriculture through the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation has released its national drought crisis management plan. This is not taken as the signal for India that drought conditions will set in, but to prepare for drought where it is identified. In the fifth week of the South-West monsoon, the trend continues to be that week by week, the number of districts which have recorded less rainfall than they normally receive outnumber those districts with normal rainfall. When this happens over a prolonged period, such as four to six weeks, drought-like conditions set in and the administration prepares for these conditions.

There are a group of ‘early warning indicators’ for the kharif crop (sowing June to August) which are looked for at this time of the year. They are: (1) delay in the onset of South-West monsoon, (2) long ‘break’ activity of the monsoon, (3) insufficient rains during June and July, (4) rise in the price of fodder, (5) absence of rising trend in the water levels of the major reservoirs, (6) drying up of sources of rural drinking water, (7) declining trend in the progress of sowing over successive weeks compared to corresponding figures for ‘normal years’.

On this list, points 1 and 2 are true, 3 is true for June and July until now, 4 and 5 are true, we have insufficient information for 6 and 7 but from mid-May there have been a number of media reports on water scarcity in the districts of peninsular, central and northern India. Thus the state of the ‘early warning’ indicators taken together have triggered the issuing of the government’s drought crisis management plan. Please read the rest at the India Climate Portal.

India’s crop quotas for a rain-troubled year

In this graphic, the size of the crop squares are relative to each other. The numbers are in million tons. Rice, wheat, pulses, coarse cereals, sugarcane. oilseeds and the fibre crops are the major categories for the 2014-15 crop production targets. What is always left out from the ‘foodgrain’-based projections are vegetables and fruit, and these I have included based on the 2013-14 advance estimates for horticultural crops.

Your allocation for the year could be 136 kilograms of vegetables, provided the monsoon holds good, which at this point in its annual career does not look likely. We need the veggies (not just potato, onion, cabbage and tomato) as much as fruit. But the central government is more traditionally concerned with ‘foodgrain’, by which is meant rice, wheat, pulses and coarse cereals.

That is what is meant by the ‘foodgrain production targets’, which have been issued by the Ministry of Agriculture for 2014-15 – as usual with scant sign of whether the Ministries of Earth Sciences and Water Resources were invited to a little chat over tea and samosas. I would have expected at least a “what do you think dear colleagues, is 94 million tons of wheat wildly optimistic given the clear blue skies that o’ertop us from Lutyens’ Delhi to Indore?” and at least some assenting murmurings from those foregathered.

But no, such niceties are not practiced by our bureaucrats. So the Ministry of Agriculture gruffly rings up the state agriculture departments, bullies them to send in the projections that make the Big Picture add up nicely, sends the tea-stained sheaf to the senior day clerk (Grade IV), and the annual hocus-pocus is readied once more. What the departments in the states say they are confident about is represented in the chart panel below, which shows you for rice, wheat, coarse cereals and pulses the produce expected from the major states. The question is: will monsoon 2014 co-operate?

A month of truant rain

We now have rain data for four complete weeks from the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and for all the districts that have reported the progress of the monsoon. The overall picture is even more serious than reported earlier because of the falling levels of water in the country’s major reservoirs. [05 to 11 June is the first week. 12 to 18 June is the second week. 19 to 25 June is the third week. 26 June to 02 July is the fourth week.]

Using the new measure of assessing the adequacy of district rainfall (and not the meteorological cgradations that is the IMD standard), in the fourth week of the monsoon the number of districts that reported normal rains in that week (+5% to -5%) is 18; deficient 1 (-6% to -20%) is 31; deficient 2 (-21% and more) is 437; excess 1 (+6% to +20%) is 17; excess 2 (+21% and more) is 113; no data was reported from 25.

Monsoon 2014 and a third dry week

05 to 11 June is the first week. 12 to 18 June is the second week. 19 to 25 June is the third week. The bars represent the weeks and are divided by IMD’s rainfall categories, with the length of each category in a bar showing the proportion of that category’s number of districts. The colours used here match those used in IMD’s weekly rainfall map (below) which displays the category-wise rainfall in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions (but not by district).

We now have rain data for three complete weeks from the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and for all the districts that have reported the progress of the monsoon.

The overall picture remains grim. In the third week of the monsoon the number of districts that reported normal rains in that week (-19% to +19% of the average) is only 74. No rain (-100%) was reported by 71 districts Scanty rain (-99% to -60%) was reported by 221 districts, deficient rain (-59% to -20%) was reported by 125 districts, excess rain (+20% and more) was reported by 129 districts, and there was no data from 21 districts.

The Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, of the Ministry of Agriculture, has already issued its guidance to states on the contingency plans to be followed for a delayed monsoon. That is why it is important to make available the district-level normals and rainfall departures – the meteorological sub-divisions are too broad for such analysis and are irrelevant to any contingency plans and remedial work.

The Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, of the Ministry of Agriculture, has already issued its guidance to states on the contingency plans to be followed for a delayed monsoon. That is why it is important to make available the district-level normals and rainfall departures – the meteorological sub-divisions are too broad for such analysis and are irrelevant to any contingency plans and remedial work.

By end-June, when the IMD updates its outlook for the rest of monsoon 2014, we expect more detailed assessments of the districts to be publicly available – the agromet (agricultural meteorology section) already provides this to the states, with state agriculture departments given the responsibility of ensuring that the advice – which is especially important for farmers to plan the sowing of crop staples – reaches every panchayat.

An epidemic of misreading rain

Who can you turn to? It’s easier to list those whom you shouldn’t turn to, the top rankers being the country’s press and television wallahs, followed at a not respectable distance by academic commentators, then come the government blokes and bureaucrats (some of whom do know the difference between isobars and salad bars, I’ll give them that). Lurking behind this cacophonous mob are the boffins of the IMD and its associated scientific chapters, a number of whom have got their sums right, but who aren’t given the space and encouragement to tell the great Bharatiya public what said public is yearning to hear simply because regulations forbid, just like it was in 1982, 1957, whenever.

As I may have mentioned before, this is Not A Good Thing. It has taken about a decade of mission mode tutoring (how the UPA bureaucrats loved that phrase, mission mode) to get the media wallahs to see the difference between weather and climate. A few may even have learned to read a wet bulb thermometer and puzzle their way through precipitation charts.

But overall, the profusion of android apps that profess to show cool graphics of clouds with lightning bolts erupting topside so that our humble ‘kisans’ know when it’s going to rain (i.e., by looking down at their screens instead of up at the sky) has not helped the Bharatiya public make more sense of less rain. We have squadrons of Insats and Kalpanas buzzing around the globe beaming pictures from the infra-red to the infra dig back home, every 60 or 90 minutes, busy enough to crash a flickr photo server, but the knowledge that said public can sift from it is sparse, rather like the rainfall over Barmer, Bikaner and Ajmer.

But overall, the profusion of android apps that profess to show cool graphics of clouds with lightning bolts erupting topside so that our humble ‘kisans’ know when it’s going to rain (i.e., by looking down at their screens instead of up at the sky) has not helped the Bharatiya public make more sense of less rain. We have squadrons of Insats and Kalpanas buzzing around the globe beaming pictures from the infra-red to the infra dig back home, every 60 or 90 minutes, busy enough to crash a flickr photo server, but the knowledge that said public can sift from it is sparse, rather like the rainfall over Barmer, Bikaner and Ajmer.

And so it goes, with the waiting for rain replacing with an equal banality waiting for Godot but with a far larger cast of characters, most of them insensible to the greater climatic drama being played out, 30,000 feet overhead, and at the poles, in the vast turquoise swells of the eastern Pacific where a malignant El Nino is brooding, in the Himalayan valleys where crystal zephyrs have been shoved aside by an airborne mat of PM2.5, or to the desiccation that creeps outwards from our towns and cities (7,935 of them, India’s triumphant ‘growth story’) that have enclosed sweeping hectares with cement, asphalt, and the hot foetid belches of factories and air-conditioners. GDP, they have been told, is the great liberator.

And that is why we have in place of the quiet concern of our forefathers in their dhotis, an electronic jumble of shrill alarm. “Weak monsoon intensifies drought like conditions in India” was one such headline, the text beneath finding the most ludicrous connections: “… threat of food inflation and weak rural demand in the first year of the Narendra Modi government”. Naturally, the cheerleaders of a demand-centric world cannot do otherwise.

And likewise with “Weak rains deliver India’s new Modi government its first economic challenge” that desultorily spies impending delays in the “sowing of main crops such as paddy, corn and sugarcane” and which notes mournfully that “about half of all farms lack irrigation systems” and, even worse, that “reservoir levels are only a fourth of last year’s levels”, this last despite the best efforts, ham-handed though they are, by the Central Water Commission to show India (for Bharat knows) that the reservoir levels in the 85 major reservoirs are low, but not much lower at this point in 2014 than they were in 2013. The GDP bullies dislike contrary numbers, and would go cross-eyed were someone to mischievously mention the existence of 4,845 large dams in India (the blue-ribboned 85 included) whose many water levels we don’t in fact know at all.

And likewise with “Weak rains deliver India’s new Modi government its first economic challenge” that desultorily spies impending delays in the “sowing of main crops such as paddy, corn and sugarcane” and which notes mournfully that “about half of all farms lack irrigation systems” and, even worse, that “reservoir levels are only a fourth of last year’s levels”, this last despite the best efforts, ham-handed though they are, by the Central Water Commission to show India (for Bharat knows) that the reservoir levels in the 85 major reservoirs are low, but not much lower at this point in 2014 than they were in 2013. The GDP bullies dislike contrary numbers, and would go cross-eyed were someone to mischievously mention the existence of 4,845 large dams in India (the blue-ribboned 85 included) whose many water levels we don’t in fact know at all.

And similar vapidity from another quarter, which like its peers cloaks ineptitude with what it takes to be appropriate jargon, “The cumulative rainfall across the country has so far been 45 per cent below the Long Period Average (LPA) for 1951-2000” and brandishes even more frightful credentials with “a further breakdown of rain data recorded in different meteorological subdivisions shows that normal rainfall has been recorded in only seven of the 36 regions”. But which sere farmer and her wise daughters consider in their universe such things as meteorological subdivisions, when their world is what Balraj Sahni and Nirupa Roy in 1953 showed us so lambently, is no more than ‘do bigha zamin’?

But still the misreading gathers pace, as vexed fixations upon an existence merely economic chase away plain common-sense. For rains may come or rains may go, but in tractors – for so we are instructed by the agents of hardened merchants – we trust. To wit: “… tractor sales have typically expanded at a double-digit pace in the years when rains have disappointed… In the 11 years between fiscal 2003 and fiscal 2013, rains fell short by 5% or more on six occasions… In four of those six years, tractor sales grew at a double-digit pace”. Let us then leave behind our cares and go rollicking over the dusty, still dustier now, plains of the Deccan in tractors tooting red.

But a shadow of monsoon yet for Bharat, and at June’s end. It is past time that the prattling ceased and the learning began.