Archive for August 2016

Disband the ministry for women and children

Perhaps better known for her penchant to find ways to police social media, the ministry headed by Maneka Gandhi has accommodated NGOs and their agendas easily.

There have in 2016 been several occasions when the work of the Ministry of Women and Child Development has come into the public glare. Not for reasons concerned with the welfare of women and children but instead for the words and actions of its minister, Maneka Sanjay Gandhi, on matters such as abuse of women in social media and paternity leave.

It is however with regard to the subjects that this ministry is concerned with – women and children of Bharat – that the most serious questions arise. As a separate ministry it is only a little over ten years old, having earlier been a department in the Ministry of Education (as the Ministry of Human Resources Development was earlier known) and with the department having been created in 1985.

What does this ministry do? In its own words: “The Ministry was constituted with the prime intention of addressing gaps in State action for women and children for promoting inter-Ministerial and inter-sectoral convergence to create gender equitable and child-centred legislation, policies and programmes.” The programmes and schemes run and managed by the ministry deal with welfare and support services for women and children, training for employment and the earning of incomes, gender sensitisation and the raising of awareness about the particular problems faced by women and children.

The ministry says that its work plays “a supplementary and complementary role to the other general developmental programmes in the sectors of health, education, rural development etc” so that women are “empowered both economically and socially and thus become equal partners in national development along with men”.

In my view there are several problems afflicting this ministry, not only in terms of what it says its work is, but also in how it goes about its work. As was the case in other countries that were once called the Third World (later called “under-developed” or “developing” countries and now called “emerging markets”), the creation of such departments or ministries came about as an adjunct to the worldwide concern about population growth, and which in Bharat had been through a particularly contentious phase in the 1970s.

Programme promotion material from the WCD. Nice pictures of children, but where are the families they belong to?

That in our case a department was turned into a ministry needs to be considered against a background that has become very relevant now, for the year was 2006 and the Millennium Development Goals (or MDGs) had gone through their first set of comprehensive reviews and ‘corrections’. It is relevant because the problems concerning how the Ministry of WCD is now going about its work has to do with the successor to the MDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Looking back even only as far as recent weeks, the view, conduct and agency of this ministry calls into question, in my view, the need for it to continue as a separate ministry. Do read TS Ranga who provides a trailer into the bewildering whims and fancies of the minister. And here is a short list of the very substantial problem areas:

1. “Healthy Food to Pregnant Women-Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)”. This means provision of supplementary nutrition to children (6 months to 6 years), pregnant women and lactating mothers. A variety of measures are needed to ensure provision: ‘Take Home Ration’, a conditional cash transfer scheme to give maternity benefit, ‘Village Health and Nutrition Days’ held monthly at anganwadi centres, tackling iron deficiency anaemia, a national conditional cash transfer to incentivise institutional delivery at public health facilities.

2. “Universal Food Fortification”. Fortification of food items like salt, edible oil, milk, wheat and rice with iron, folic acid, Vitamin-D and Vitamin-A “to address the issue of malnutrition and to evolve a policy and draft legislation/regulation on micronutrient fortification”.

3. “Beneficiaries of Supplementary Nutrition Programme under ICDS”. The increase in the number of beneficiaries is linked to the “Development Agenda for 2016-2030 of the United Nations” (the SDGs). The ministry delivers three of six ICDS services through the public health infrastructure under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare.

4. “National Plan of Action for Children 2016”. The draft plan is based on principles contained in the National Policy for Children 2013 and categorises the rights of the children under four areas. The draft is being developed by ministries, state governments, and civil society organisations.

5. “ICDS Being Completely Revamped To Address The Issue Of Malnutrition”. The ministry is undertaking a complete revamp of the ICDS programme as the level of malnutrition in the country continues to be high. The digitisation of anganwadis is being taken up for real-time monitoring of every child and every pregnant and lactating mother. The ministry wants supplementary nutrition to be standardised through both manufacturing and distribution.

A great deal about ‘nutrition’, but nothing about the agricultural environment which supplies the nutrition. Unless by ‘nutrition’ the WCD considers only what MNCs produce as supplements and food ‘fortification’.

6. “WCD Ministry and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation sign Memorandum of Cooperation”. The memorandum is for technical support to strengthen the nutrition programme in Bharat and includes ICT-based real-time monitoring of ICDS services. The motive is for national and state capacities to be strengthened to deliver nutrition interventions during pre-conception, pregnancy and first two years of life. There will be technological innovation, sharing best practices and use of data and evidence.

7. “ICT enabled Real-Time Monitoring System of ICDS”. The web-enabled online digitisation “will strengthen the monitoring of the service delivery of anganwadis, help improve the nutrition levels of children and help meet nutrition goals”. This will help draw the nutrition profile of each village and address the problem of malnutrition by getting real-time reports from the grassroot level. It will start with a project assisted by International Development Association (IDA) in 162 high burden districts of eight states covering 3.68 lakh anganwadis.

8. “Draft National Policy for Women, 2016”. The policy is being revised after 15 years and is expeceted to guide Government action on women’s issues over the next 15-20 years. “Several things have changed since the last policy of 2001 especially women’s attitude towards themselves and their expectations from life”.

9. “Stakeholders Consultations Held For Policy On Food Fortification“. A consultation with stakeholders was held to evolve a comprehensive policy including draft regulations on micronutrient fortification.

What do these tell us?

a) The ministry does not consider either women or children to be part of a family, or an extended family, or a joint family, nor are they part of a village community consisting of peers and elders. The extremely essential months during which women conceive, the post natal period, and the life of the infant until the age of two or three is – under this view – to be monitored and governed by the ministry and its agents. There is in neither of the draft plans mentioned in the points above the briefest mention of culture or community.

b) Such a view, distasteful and profoundly disruptive as it is to the institution of family, has come about because of the influences upon the ministry. Women and children are seen in this view as factors of consumption even within the family, and the decisions pertaining to what they consume, how much and when are to be controlled for lengthy periods of time by implementers and partners of the ministry’s programmes and schemes, which themselves are shaped by an international list called the SDGs in whose framing these women, children and their families played no part.

c) Sheltering behind the excuse of delivering the services of the ICDS, the ministry through its association with the Gates Foundation plans to collect at an individual level the medical data of millions of infants and mothers, for use as evidence. By whom? By the partners of the Gates Foundation and its allies which are the multi-national pharmaceutical industry, the multi-national agriculture and crop science industry and the multi-national processed foods industry. Hence we see the insistence on biofortification, micronutrients, ready-to-eat take-home rations and the money being provided (by the government through cash transfers) to buy these substances. The ICDS budget for the duration of the Twelfth Five Year Plan which ends in March 2017 is Rs 1,23,580 crore – a gigantic sum distributed amongst several thousand projects with a few hundred local implementing agencies including NGOs.

d) These objectives alone are reason enough to have the officials concerned, including the minister, immediately suspended and charge-sheeted for conspiracy against the public of Bharat. It is far beyond shameful that the valid reasons of malnutrition and gaps in the provision of essential services are being twisted in a manner that can scarcely be grasped. The 10.3 million children and women that are in the ICDS ‘supplementary nutrition’ net today form potentially the largest legitimised medical trial in the world, but with none of the due diligence, informed consent and independent supervision required for such trials in the so-called developed countries.

e) The ministry is entirely in thrall to its foreign ‘development partners’ – UNICEF, World Bank, DFID, WFP and USAID. For this reason the ministry has had the closest and cosiest of arrangements, from amongst all central ministries, with non-government organisations (NGOs) foreign and national. The international bodies such as UNICEF and the World Food Program (WFP) and the large national aid agencies (Britain’s DFID and the USA’s USAID) provide programme funding to NGOs international and national who work with and advise the WCD ministry. In the 2000s this was in order to comply with the Millennium Development Goals, now it is for the SDGs, and this is why the policy view of the ministry aligns with the UN SDGs rather than with the needs of our families whether rural or urban.

What is the remedy? The ministry manages several programmes that are critical for a large number of families all over Bharat. However these are programmes that have much in common with the aims and programmes of three ministries in particular: the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, and the Ministry of Human Resources Development (for matters pertaining to regulation and policy, the Ministry of Law and justice). These three ministries become the natural recipients of the responsibilities borne thus far by the Ministry of Women and Child Development and when such a transfer of allied duties is effected, some of the most important years in the lives of the children and women of Bharat will not become data points and consumption instances for corporations but return to being families.

Environmental law and the dharmic principle

The recent history of “global” approaches to the environment has shown that they began full of contradictions and misunderstandings, which have continued to proliferate under a veneer of internationalisation. To provide but a very brief roster, there was in the 1970s the “Club of Rome” reports, as well as the United Nations Conference on Human Environment in 1972 (which produced the so-called Stockholm Declaration). In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro) was held and was pompously called the “Earth Summit,” where something called a “global community” adopted an “Agenda 21.” With very much less fanfare also in 1992 came the Convention on Biological Diversity, and signing countries were obliged to “conserve and sustainably manage their biological resources through global agreement,” an operational conundrum when said resources are national and not international.

The recent history of “global” approaches to the environment has shown that they began full of contradictions and misunderstandings, which have continued to proliferate under a veneer of internationalisation. To provide but a very brief roster, there was in the 1970s the “Club of Rome” reports, as well as the United Nations Conference on Human Environment in 1972 (which produced the so-called Stockholm Declaration). In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro) was held and was pompously called the “Earth Summit,” where something called a “global community” adopted an “Agenda 21.” With very much less fanfare also in 1992 came the Convention on Biological Diversity, and signing countries were obliged to “conserve and sustainably manage their biological resources through global agreement,” an operational conundrum when said resources are national and not international.

In 2000 came the “Millennium Summit,” at which were unveiled the Millennium Development Goals, which successfully incubated the industry of international development but had almost nothing to do with the mundane practice of local development. In 2015 came the UN Sustainable Development Summit, which released a shinier, heftier, more thrillingly complex list of sustainable development goals. During the years in between, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and its associated satellite meetings (three or four a year) spun through every calendar year like a merry-go-round (it is 22 years old, and the very global CO2 measure for PPM, or parts per million, has crossed 400).

The visarjan (immersion) of Shri Ganesh. The idol is accompanied by huge crowds in Mumbai. Photo: All India Radio

Looking back at some five decades of internationalisation as a means to some sort of sensible stock-taking of the connection between the behaviors of societies (ever more homogenous) and the effects of those behaviors upon nature and environment, I think it has been an expensive, verbose, distracting, and inconclusive engagement (but not for the bureaucratic class it sustains, and the “global development” financiers, of course). That is why I find seeking some consensus between countries and between cultures on “ecocide” is rather a nonstarter. There are many differences about meaning, as there should be if there are living cultures left amongst us.

Even before you approach such an idea (not that it should be approached as an idea that distinguishes a more “advanced” society from one apparently less so), there are other ideas, which from some points of view are more deserving of our attention, which have remained inconclusive internationally and even nationally for fifty years and more. Some of these ideas are, what is poverty, and how do we say a family is poor or not? What is economy and how can our community distinguish economic activity from other kinds of activity (and why should we in the first place)? What is “education,” and what is “progress”-and whose ideas about these things matter other than our own?

That is why even though it may be academically appealing to consider what ecocide may entail and how to deal with it, I think it will continue to be subservient to several other very pressing concerns, for very good reasons. Nonetheless, there have in the very recent past been some efforts, and some signal successes too, in the area of finding evidence and intent about a crime against nature or, from a standpoint that has nothing whatsoever to do with law and jurisprudence, against the natural order (which we ought to observe but for shabby reasons of economics, career, standard of living, etc., do not).

Clay cooking pots and decorative terracotta. A craftsman and his wares at a weekly market in Kerala.

These efforts include Bolivia’s Law of the Rights of Mother Earth, whose elaborate elucidation in 2010 gave environmentalists much to cheer about. They also include the recognition by the UN Environment Programme, in incremental doses and as a carefully measured response to literally mountainous evidence, of environmental crime. This is what the UNEP now says, “A broad understanding of environmental crime includes threat finance from exploitation of natural resources such as minerals, oil, timber, charcoal, marine resources, financial crimes in natural resources, laundering, tax fraud and illegal trade in hazardous waste and chemicals, as well as the environmental impacts of illegal exploitation and extraction of natural resources.” Quite frank, I would say, and unusually so for a UN agency.

Moreover, there is the Monsanto Tribunal, which is described as an international civil society initiative to hold Monsanto-the producer of genetically modified (GM) seed, and in many eyes the most despised corporation ever-“accountable for human rights violations, for crimes against humanity, and for ecocide.” In the tribunal’s description of its rationale, ecocide is explicitly mentioned, and the tribunal intends to follow procedures of the International Court of Justice. It is no surprise that Monsanto (together with corporations like Syngenta, Dow, Bayer, and DuPont) is the symbol of industrial agriculture whose object and methods advance any definition of ecocide, country by country.

This ecocidal corporation (whose stock is traded on all major stock markets, which couldn’t care less about the tribunal) is responsible for extinguishing entire species and causing the decline of biodiversity wherever its products are used, for the depletion of soil fertility and of water resources, and for causing an unknown (but certainly very large) number of smallholder farming families to exit farming and usually their land, therefore also exiting the locale in which bodies of traditional knowledge found expression. Likewise, there is the group of Filipino investigators, a Commission on Human Rights, who want forty-seven corporate polluters to answer allegations of human rights abuses, with the polluters being fossil fuel and cement companies, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP, and the allegations include the roles of these corporations’ products in causing both “global warming and the harm that follows.”

A ‘gudi’ and ‘bhagwa dhvaj’ hoisted by a home in Goa for Gudi Padwa, the festival which marks the beginning of the new year.

Such examples show that there is a fairly strong and active manifestation of the movement to recognise ecocide as a crime under international law. However, to find such manifestations, one has to look at the local level. There, the questions pertain more tangibly to the who, what, and how of the ecological or environmental transgression, and the how much of punishment becomes more readily quantifiable (we must see what forms of punishment or reparation are contained in the judgments of the Monsanto Tribunal and the Philippines Commission).

Considering such views, the problem becomes more immediate but also more of a problem-the products of industrialised, mechanised agriculture that is decontextualised from culture and community exists and are sold and bought because of the manner in which societies sustain themselves, consciously or not. It is easier to find evidence for, and easier to frame a prosecution or, the illegality of a corporation, or of an industry, than for the negligence of a community which consumes their products. So the internationalisation (or globalisation) of the idea of ecocide may take shape in a bubble of case law prose and citations from intergovernmental treaties but will be unintelligible to district administrators and councils of village elders.

My view is that searching for the concept which for the sake of semantic convenience we have called ecocide as an outcome of an “internationally agreed” idea of crime and punishment will ultimately not help us. I have such a view because of a cultural upbringing in a Hindu civilisation, of which I am a part, and in which there exists an all-embracing concept, “dharma,” that occupies the whole spectrum of moral, religious, customary, and legal rules. In this view, right conduct is required at every level (and dominates its judicial process too), with our literature on the subject being truly voluminous (including sacred texts themselves, the upanishads, various puranas, and works on dharma).

Perhaps the best known to the West from amongst this corpus is the Arthashastra of Kautilya, a remarkable legal treatise dealing with royal duties which contains a fine degree of detail about the duties of kings (which may today be read as “governance”). This treatise includes the protection of canals, lakes, and rivers; the regulation of mines (the BCE analogue of the extractive industries that plague us today); and the conservation of forests. My preference is for the subject of ecocide and its treatment to be subsumed into the cultural foundation where it is to be considered for, when compared with how my culture and others have treated the nature-human question, it becomes evident that we today are not the most competent arbiters, when considering time frames over many generations, about how to define or address such matters. The insistence on “globalising” views in fact shows why not.

(This comment has been posted at the Great Transition Initiative in reply to an essay titled ‘Against Ecocide: Legal Protection for Earth’.)

Why our kisans must make sustainable crop choices

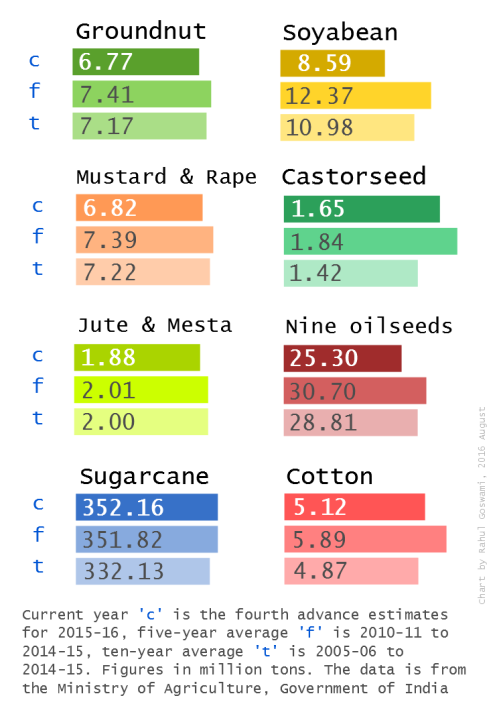

The 2015-16 fourth advance estimates for commercial crops, when compared with the annual averages for five year and ten year periods, visibly displays the need for more rational crop choices to be made at the level of district (and below), in agro-ecological regions and river sub-basins.

For this rapid overview of the output of commercial crops for 2015-16 I have compared the Fourth Advance Estimates of agricultural production, which have just been released by the Ministry of Agriculture, with two other kinds of production figures. One is the five-year average until 2014-15 and the second is the ten-year average until 2014-15.

For this rapid overview of the output of commercial crops for 2015-16 I have compared the Fourth Advance Estimates of agricultural production, which have just been released by the Ministry of Agriculture, with two other kinds of production figures. One is the five-year average until 2014-15 and the second is the ten-year average until 2014-15.

While a yearwise comparison is often used to show the variation in produced crops (which are affected by price changes, policies, adequacy of the monsoon and climatic conditions), it is important to compare a current year’s nearly final crop production estimate with longer term averages. Doing so allows us to smooth the effects of variations in individual years and so gauge the performance in the current year against a wider recent historical pattern. (See ‘How our kisans bested drought to give 252.2 mt’.)

The output of the nine oilseeds taken together is less than both the five-year and ten-year averages. Significant drops are seen in the production of soyabean, groundnut and mustard and rape – these three account for 88% of the quantity of the nine oilseeds (castorseed, sesamum, nigerseed, linseed, safflower and sunflower are the others). Between the fibre crops – cotton, and jute and mesta – the output of cotton is considerably under the five-year average, while that of jute and mesta is under both the five and ten year averages.

It is in the figures for sugarcane that the message lies. The 2015-16 output of sugarcane is marginally above the five-year average and handily above the ten-year average. This needs to be considered against the background of two drought years (2014 and 2015) and the drought-like conditions that were experienced in many parts of the country during March to May 2016.

As these are near-final estimates, this only means that the allocation of water for such a large crop quantity – 352 million tons of sugarcane is about 100 mt more than the foodgrains output of 252 mt – was assured even during times of severe shortage of water.

This is a comparison that needs urgent and serious study, not with a view to change overall policy but to decentralise how crop – and therefore inputs and water – choices are determined locally so that self-sufficiency in food staples and the sustainability of cash crops can be achieved. These are quantities only and do not tell us the burdens of inputs (chemical fertiliser, hazardous pesticides, malignant credit terms) or the risks (as cotton cultivators have experienced this year) but where these are known from past experience their effects can well be gauged.

How our kisans bested drought to give 252.2 mt

Bharat has maintained a level of foodgrains production that is above 250 million tons for the year 2015-16. This is the most important signal from the Fourth Advance Estimates of agricultural production, which have just been released by the Ministry of Agriculture. The ‘advance estimates’, four in the agricultural year, mark the progression from target production for the year to actual output.

Bharat has maintained a level of foodgrains production that is above 250 million tons for the year 2015-16. This is the most important signal from the Fourth Advance Estimates of agricultural production, which have just been released by the Ministry of Agriculture. The ‘advance estimates’, four in the agricultural year, mark the progression from target production for the year to actual output.

For this rapid overview I have compared the 2015-16 fourth estimates, which will with minor adjustments become the final tally, with two other kinds of production figures. One is the five-year average until 2014-15 and the second is the ten-year average until 2014-15. While a yearwise comparison is often used to show the variation in produced crops (which are affected by price changes, policies, adequacy of the monsoon and climatic conditions), it is important to compare a current year’s nearly final crop production estimate with longer term averages. Doing so allows us to dampen the effects of variations in individual years and so gauge the performance in the current year against a wider recent historical pattern.

In this way we see that for all foodgrains (rice, wheat, coarse cereals and pulses) the production for 2015-16 is about three million tons below the five-year average but about 13.5 million tons above the ten-year average. These two comparisons need to be considered against the growing conditions our kisans dealt with during 2015 and 2014, both of which were drought years. They also need to be viewed against economic and demographic conditions, which have led to migration of agriculturalists and cultivators from villages into urban settlements (hence less available hands in the field), and the incremental degradation of agro-ecological growing regions (because of both urban settlements that grow and because of increased industrialisation, and therefore industrial pollution and the contamination of soil and water).

That the total quantity of foodgrains is adequate however has been due to the production of rice and wheat (चावल, गेंहूँ) both being above the five and ten year averages. There is undoubtedly regional variation in production (the February to May months in 2016 were marked by exceedingly hot weather in several growing regions, with difficult conditions made worse by water shortages). There is likewise the effects of more transparent procurement policies and stronger commitments being followed by state governments to adhere to or better the recommendations on minimum support prices. The host of contributing factors require inquiry and study.

What requires more urgent attention are the production figures for coarse cereals and pulses. Coarse cereals (which includes jowar, bajra, maize, ragi, small millets and barley – ज्वार, बाजरा, मक्का, रागी, छोटे अनाज, जौ) at just under 40 million tons is 4.4 million tons under the five-year average and 1.4 million tons under the ten-year average. Likewise pulses (which includes tur or arhar, gram, urad, moong, other kharif and other rabi pulses – अरहर, चना, उरद, मूँग, अन्य खरीफ दालें, अन्य रबी दालें) is 1.6 million tons under the five-year average and only 0.3 million tons above the ten-year average. The low total production of these crop types, coarse cereals and pulses, have continued to be a challenge for over a generation. The surprisingly good outputs of wheat (9.3 mt above the ten-year average) and rice (5.5 mt above the ten-year average) should not be allowed to obscure the persistent problems signalled by the outputs of coarse cereals and pulses.