Posts Tagged ‘poverty’

Food, climate, culture, crops and government

The weekly standardised precipitation index of the India Meteorological Department (IMD) which is a running four-week average. This series shows the advancing dryness of districts in south India.

In November 2015, the Departmentally Related Standing Committee on Agriculture of the Lok Sabha, Parliament of India, invited suggestions and submissions on the subject “Comprehensive Agriculture Research based on Geographical Condition and Impact of Climatic Changes to ensure Food Security in the Country”.

The Committee called for inputs on issues such as the need to evolve new varieties of crops which can withstand climatic fluctuation; requirement to evolve improved methods of irrigation; the need to popularise consumption of crops/fruits which can provide better nutrition; the need to develop indigenous varieties of cattle that can withstand extreme climatic stress; the need to develop a system for precision horticulture and protected cultivation; diversification of species of fish to enhance production from the fisheries sector; the need to strengthen the agriculture extension system; and means to focus on agriculture education.

I prepared a submission as my outline response, titled “Aspects of cultivation, provision of food, and use of land in Bharat today and a generation hence”. The outline I provided includes several issues of current urgency and connects them to scenarios that are very likely to emerge within a generation. My intention is to signal the kinds of pathways to preparation that government (central and state) may consider. It is also meant to flag important cultural and social considerations that lie before us, and to emphasise that economic and quantitative measurements alone are not equipped to provide us holistic guidance.

The outline comprises three sections.

(A) The economic framework of the agriculture and food sector and its imperatives.

(B) The social, ecological, and resource nature of crop cultivation, considering factors that influence it.

(C) Methods, pathways and alternatives possible to adopt with a view to being inter-generationally responsible.

In view of the current climatic conditions – heat waves in the central and eastern regions of the country, stored water in our major reservoirs which are at or near ten-year lows – I reproduce here the section on the economic framework of the agriculture and food sector and its imperatives. The full submission can be found here [pdf, 125kb].

This framework considers the agriculture and food sector, including primary agricultural production recorded, the inputs and products of industry based on agricultural raw material (primary crop whether foodgrain, horticulture, spices, plantation, ruminants and marine, oilseeds, fibres), agribusiness (processing in all its forms), supply chains connecting farmers and farmer producer organisations to primary crop aggregators, buyers, merchants, stockists, traders, consumers, as well as associated service providers. This approach is based on the connection between agricultural production and demand from buyers, processers and consumers along what is called the supply chain.

Water storage quantities in the 91 major reservoirs in the first week of April 2016. Blue bars are each reservoir’s full storage capacity (in billion cubic metres, bcm) and orange bars are the current storage at the time. Data from the Central Water Commission, Government of India.

If this framework is considered as existing in Bharat to a significant degree which influences crop cultivation choices, the income of cultivating household, the employment generation potential of associated service providers, then several sets of questions require answers:

* Concerning economic well-being and poverty reduction: what role does agricultural development need to play in promoting economic stability in rural (and peri-urban) regions thereby contributing to poverty reduction and how can the agrifood sector best contribute to jobs and higher incomes for the rural poor?

* Concerning food security: what role can agricultural and agro-industry development play in ensuring rural and urban communities have reliable access to sufficient, culturally appropriate and safe food?

* Concerning the sustainability of food producing systems: how should agriculture and agro-industry be regulated in a participatory manner so as to ensure that methods of production do not overshoot or endanger in any way (ecological or social) conservative carrying capacity thresholds especially in the contexts of climate change and resource scarcity?

When viewed according to the administrative and policy view that has prevailed in Bharat over the last two generations, there is a correlation between agricultural productivity growth and poverty reduction and this is the relationship the macro- economic and policy calculations have been based upon. Our central annual agricultural (and allied services) annual and five-year plan budget and state annual and five-year plan budgets have employed such calculations since the 1950s, when central planning began.

However the choices that remain open to us are considerably fewer now than was the case two generations (and more) ago when the conventional economic framework of the agriculture and food sector took shape.

Ten years of India’s great rural guarantee

Ten years of a rural employment guarantee programme in India is well worth marking for the transformations it has brought about in rural districts and urban towns both, for the two kinds of Indias are so closely interlinked. The ten year mark has been surrounded by opportunistic political posturing of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of the ruling National Democratic Alliance and by churlish accusations from the Indian National Congress (or Congress party, now in the opposition).

Ten years of a rural employment guarantee programme in India is well worth marking for the transformations it has brought about in rural districts and urban towns both, for the two kinds of Indias are so closely interlinked. The ten year mark has been surrounded by opportunistic political posturing of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of the ruling National Democratic Alliance and by churlish accusations from the Indian National Congress (or Congress party, now in the opposition).

When the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act came about (it is now prefixed by MG, which is Mahatma Gandhi) ten years ago, it was only the newest in a long line of rural poverty alleviation programmes whose beginnings stretch past the Integrated Rural Development Programme (still a touchstone during the Ninth Five Year Plan) whose early period dates from the 1970s as a more coherent manifestation of the ‘Food For Work’ programme. Democratic decentralisation, which is casually dropped into central government communications nowadays as if it was invented only last week, was explained at length as early as the Sixth Five Year Plan. And in the Fourth Five Year Plan, in the guidance section it was stated that measures were needed for “widening opportunities of productive work and employment to the common man and particularly the less privileged sections of society” which “have to be thought out in a number of different contexts and coordinated in to effective, integrated programmes”.

Work demand patterns in four districts (all in Maharashtra) from 2012 April to 2016 February. The cyclical nature of work demanded usually coincides with crop calendar activities in districts and sub-districts. This aspect of the MGNREGA information system can be used as a good indicator for planning by other line ministries, not only rural development. We can see the difference between the set of two districts of Akola and Gondiya, and the districts of Washim and Hingoli: the cyclical nature in the first two is more pronounced. The April to June demand is seen common, and increasing over the three years recorded by the charts.

This is only the barest glimpse of the historical precursors to the MGNREGA. The size of our rural population in the decade of the 2010s transforms any national (central government) programme into a study of gigantism over a number of dimensions, and so it is with the (MG)NREGA whose procedural demands for organising information over time and place became a discipline by itself, leading to the creation of a management information system whose levels of detail are probably unmatched anywhere in the world.

For its administrators, every week that the MGNREGA delivers money to households in a hamlet for work sanctioned by that small panchayat is one more successful week. There have over this last decade been considerably more successful weeks than unsuccessful ones. This has happened not because of politicians of whichever party of persuasion, but because of the decision made by many households to participate in the shape that NREGA (and later MGNREGA) took in their particular village. The politicians, like the parties they belong to, are incidental and transitory. At this stage of the programme’s life, it is to be hoped that it continues to run as a participatory pillar of the economy of Bharat, and assimilates in the years to come new concerns from the domains of organic (or zero budget) agriculture, sustainable development and ecological conservation.

At this stage the commentaries look back at the last year or perhaps two of the programme. “It is unclear, however, what the present NDA government thinks about the performance of the scheme,” commented the periodical Down To Earth. “Last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi called MGNREGA a ‘monument of failure’. Now, the rural development ministry has termed it as ‘a cause of national pride’.” The magazine went on to add that MGNREGA “started losing steam when wages were kept pending, leading to the liability being carried forward to the following year”.

“What is relatively less known is the impact of MGNREGA on several other aspects of the rural economy, such as wages, agricultural productivity and gender empowerment,” a commentary in the financial daily Mint has pointed out. “While most critics lament the quality of assets created under MGNREGA, there is now increasing evidence based on rigorous studies, which suggest that not only has the asset quality been better than comparable government programmes, they are also used more by the community.”

The finance minister has been quoted by the daily Indian Express as follows: “A kind of indifference towards it (MGNREGA) was growing by 2013-14, when the scheme entered its seventh and eighth years. When there was a change of government in 2014-15, there was talk on whether the scheme will be discontinued, or its fund allocation curtailed,” Minister Arun Jaitley is reported to have said at the MGNREGA ‘Sammelan’ in New Delhi. “The new government [the BJP] not only took forward the scheme but also increased its fund.”

In a Press Information Bureau release, the Minister for Rural Development, Birender Singh, said that 2015-16 has seen a revival of the MGNREGA programme. He also said that more than 64% of total expenditure was on agriculture and allied activities and 57% of all workers were women (well above the statutory requirement of 33%), and that among the measures responsible for the “revival of MGNREGA are the timely release of funds to states to provide work on demand, an electronic fund management system, consistent coordination between banks and post offices besides monitoring of pendency of payments”.

So far so good. What MGNREGA administrators need to mind now is for managerial technology and methods to not get ahead (or around) the objectives of the programme because these tend to keep the poor and vulnerable out instead of the other way around. The evaluations and studies on NREGA – and there have been a number of good ones – have shown that the more new financial and administrative measures there are, the greater the decline in participation in the programme. Administrative complexity also provides fodder to those, like this pompous commentator, who try to find in data ‘evidence’ that NREGA does “not help the poor”.

So far so good. What MGNREGA administrators need to mind now is for managerial technology and methods to not get ahead (or around) the objectives of the programme because these tend to keep the poor and vulnerable out instead of the other way around. The evaluations and studies on NREGA – and there have been a number of good ones – have shown that the more new financial and administrative measures there are, the greater the decline in participation in the programme. Administrative complexity also provides fodder to those, like this pompous commentator, who try to find in data ‘evidence’ that NREGA does “not help the poor”.

The MGNREGA’s usefulness and relevance is not only about creating employment when it is needed and its generally positive impact on wages. For all its shortcomings the MGNREGA programme has also helped revitalise the need to understand labour dynamics in rural areas particularly as it pertains to agriculture and cultivation. At a time when the flashier sections of the modern economy have lost their shine (if ever there was a shine) and when the need for panchayat-led, village-centric development that is self-reliant in deed and spirit is growing in Bharat, a programme like the MGNREGA has all the potential to serve the country well for another generation.

The uses of a Nobel prize in economics

The 2015 Nobel prize for economics has been awarded to Angus Deaton, who is based in the Princeton University, in USA. Deaton’s work has been on poverty and his contemporaries in the field are Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze; all three have focused on poverty, malnutrition, consumption by households and how to measure these.

Herewith my view which I set out in a series of 37 tweets:

1 – like every single Nobel award category, the one for economics is calculated recognition of the use of Western ideas.

2 – There is no Nobel in economics for, say, Pacific islander economics or nomadic/pastoral economics. The boundary is clear.

3 – There is the additional problem, and it is a weighty one, of what is being recognised: a science or a thought experiment?

4 – Western economics can only ever and at best pretend to be a science (ignore the silly equations). There’s more.

5 – It has to do with food and food consumption choices. Do remember that. For the last 5-6 years the food MNCs and their..

6 – collaborators in Bharat have moved from hunger to nutrition. Remember that we grow enough food for all our households..

7 – and there are in 2016 about 175 million rural and 83 million urban households. So, food is there but choice is not yet..

8 – as clear as the marketeers and retailers pretend. No one truly knows, but economists claim to, and this one does.

9 – What then follows is the academic deification of the thought experiment, done carefully over a decade. The defenders..

10 – of the postulations of Deaton, Dreze, Sen et al turn this into a handmaiden of poverty study. And India is poor..

11 – (but Bharat is not). So we now have consumer choice, poverty, malnutrition and a unified theory to bridge the mess..

12 – for such a third world mess can only find salvation through the scientific ministrations of Western economics. The stage

13 – was thus set some years ago, when the Congress/UPA strove abundantly to craft a halo for this thought experiment..

14 – and in the process, all other explanations concerning food and the manner of its many uses were banished from both..

15 – policy and the academic trend of the day. But Deaton’s experiment is only as good as his references, which aren’t..

16 – for the references, as any kirana shop owner and any mandi bania knows, are more unreliable than reliable. What our..

17 – primary crop quantities are have only ever been a best estimate subject to abundant caution and local interpretation..

18 – for a thought experiment which seeks to unify food, malnutrition, poverty and ‘development’ this one has clay feet..

19 – which nevertheless is good enough for the lords of food crop and seed of the world, for it takes only the shimmer of..

20 – academic respectability such as that accumulated by Deaton, Dreze and Sen to turn postulate into programme. What we..

21 – will now see is what has been seen in medicine (and therefore public health) and in ‘peace’ (hence geopolitics) because..

22 – of the benediction the Nobel aura confers. This work will be press-ganged into the service of the new nutritionists..

23 – whose numbers are growing more rapidly than, a generation ago, did the numbers of the poverty experts. It is no longer..

24 – food and hunger and malnutrition but consumer choice, nutrition and the illusions of welfare. This is the masala mix..

25 – seized upon by those who direct the Nobel committee as they seek to control our 105 million tons of rice, 95 of wheat..

26 – our 43 million tons of coarse cereals, 20 of pulses, 170 of vegetables and 85 of fruit and turn this primary wealth..

27 – of our Bharat into a finance-capital manifesto outfitted with Nobel armoury that is intended to strip choice (not to..

28 – support it) from our kisans who labour on the 138 million farm holdings of our country (85% of them small and marginal)..

29 – and from our 258 million households (as they will be next year) towards whose thalis is destined the biofortified and..

30 – genetically modified menace of hyper-processed primary crop that is digitally retailed and cunningly marketed. This..

31 – is the deft and cunning manoeuvring that has picked on the microeconomist of post-poverty food study aka nutrition..

32 – as being deserving of Nobel recognition (when five years ago the Nobel family dissociated itself from this category).

33 – And so the coast has been duly cleared. The troublesome detritus of poverty macro-economics has been replaced by the..

34 – big data-friendliness of a rickety thought experiment which lends itself admirably to a high-fashion ‘development’..

35 – industry that basks in ‘sustainable’ hues and reflects the technology-finance tendencies of the SDGs. Food is no longer..

36 – in vogue but the atomisation of community crop and diet choice most certainly is. The pirate pennant of Western macro-

37 – economics is all aflutter again, thanks to the Nobel wind of 2015, but I will not allow it to fly over my Bharat. Never.

PS: The Western media has as usual waxed cluelessly eloquent on the selection of the award winner. This is the new York Times writing itself breathless about what this means for understanding the situation of the poor in the global economy. There is an account from Princeton [pdf] on the measuring of poverty, which has now become such a burgeoning industry. The statement of the committee which awarded this economist is here, with a more detailed version here [pdf].

To localise and humanise India’s urban project

Cities and towns have outdated and inadequate master plans that are unable to address the needs of inhabitants. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here, part two is found here, part three is here and this is part four:

The reason they pursue this objective in so predatory a manner is the potential of GDP being concentrated – their guides, the international management consulting companies (such as McKinsey, PriceWaterhouse Coopers, Deloitte, Ernst and Young, Accenture and so on), have determined India’s unique selling proposition to the world for the first half of the 21st century. It runs like this: “Employment opportunities in urban cities will prove to be a catalyst for economic growth, creating 70% of net new jobs while contributing in excess of 70% to India’s GDP.” Naturally, the steps required to ensure such a concentration of people and wealth-making capacity include building new urban infrastructure (and rebuilding what exists, regardless of whether it serves the ward populations or not).

“Employment opportunities in urban cities will prove to be a catalyst for economic growth” is the usual excuse given for the sort of built superscale seen in this metro suburb. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

The sums being floated today for achieving this camouflaged subjugation of urban populations defy common sense, for any number between Rs 5 million crore and Rs 7 million crore is being proposed, since an “investment outlay will create a huge demand in various core and ancillary sectors causing a multiplier effect through inter-linkages between 254 industries including those in infrastructure, logistics and modern retail… it will help promote social stability and economic equality through all-round development of urban economic centres and shall improve synergies between urban and rural centres”.

Tiers of overlapping programmes and a maze of controls via agencies shaded in sombre government hues to bright private sector colours are already well assembled and provided governance fiat to realise this ‘transformation’, as every government since the Tenth Plan has called it (the present new government included). For all the academic originality claimed by a host of new urban planning and habitat research institutes in India (many with faculty active in the United Nations circuits that gravely discuss the fate of cities; for we have spawned a new brigade of Indian – though not Bharatiya – urban studies brahmins adept at deconstructing the city but ignorant of such essentials as ward-level food demand), city planning remains a signal failure.

Typically, democratisation and self-determination is permitted only in controlled conditions. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

Other than the metropolitan cities and a small clutch of others (thanks to the efforts of a few administrative individuals who valued humanism above GDP), cities and towns have outdated and inadequate master plans that are unable to address the needs of city inhabitants in general (and of migrants in particular). These plans, where they exist, are technically prepared and bureaucratically envisioned with little involvement of citizens, and so the instruments of exclusion have been successfully transferred to the new frameworks that determine city-building in India.

Democratisation and self-determination is permitted only in controlled conditions and with ‘deliverables’ and ‘outcomes’ attached – organic ward committees and residents groups that have not influenced the vision and text of a city master plan have even less scope today to do so inside the maze of technocratic and finance-heavy social re-engineering represented by the JNNURM, RAY, UIDSSMT, BSUP, IHSDP and NULM and all their efficiently bristling sub-components. The rights of inhabitants to a comfortable standard of life that does not disturb environmental limits, to adequate and affordable housing, to safe and reliable water and sanitation, to holistic education and healthcare, and most of all the right to alter their habitats and processes of administration according to their needs, all are circumscribed by outside agencies.

Managed socialisation in our cities and towns must give way to organic groups. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

It is not too late to find remedies and corrections. “As long as the machinery is the same, if we are simply depending on the idealism of the men at the helm, we are running a grave risk. The Indian genius has ever been to create organisations which are impersonal and are self-acting. Mere socialisation of the functions will not solve our problem.” So J C Kumarappa had advised (the Kumarappa Papers, 1939-46) about 80 years ago, advice that is as sensible in the bastis of today as it was to the artisans and craftspeople of his era.

For the managed socialisation of the urbanisation project to give way to organic groups working to build the beginnings of simpler ways in their communities will require recognition of these elements of independence now. It is the localisation of our towns and cities that can provide a base for reconstruction when existing and planned urban systems fail. Today some of these are finding ‘swadeshi’ within a consumer-capitalist society that sees them as EWS, LIG and migrants, and it is their stories that must guide urban India.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

India’s writing of the urbanised middle-class symphony

The maintaining of and adding to the numbers of the middle class is what the growth of India’s GDP relies upon. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here, part two is found here, and this is part three:

A small matrix of classifications is the reason for such obtuseness, which any kirana shop owner and his speedy delivery boys could quickly debunk. As with the viewing of ‘poverty’ so too the consideration of an income level as the passport between economic strata (or classes) in a city: the Ministry of Housing follows the classification that a household whose income is up to Rs 5,000 a month is pigeon-holed as belonging to the economically weaker section while another whose income is Rs 5,001 and above up to Rs 10,000 is similarly treated as lower income group.

Committees and panels studying our urban condition are enjoined not to stray outside these markers if they want their reports to find official audiences, and so they do, as did the work (in 2012) of the Technical Group on Urban Housing Shortage over the Twelfth Plan period (which is 2012-17). Central trade unions were already at the time stridently demanding that Rs 10,000 be the national minimum wage, and stating that their calculation was already conservative (so it was, for the rise in the prices of food staples had begun two years earlier).

The contributions of those in the lower economic strata (not the ‘poor’ alone, however they are measured or miscounted) to the cities of India and the towns of Bharat, to the urban agglomerations and outgrowths (terms that conceal the entombment of hundreds of hectares of growing soil in cement and rubble so that more bastis may be accommodated), are only erratically recorded. When this is done, more often than not by an NGO, or a research institute (not necessarily on urban studies) or a more enlightened university programme, seldom do the findings make their way through the grimy corridors of the municipal councils and into recognition of the success or failure of urban policy.

Until 10 years ago, it was still being said in government circles that India’s pace of urbanisation was only ‘modest’ by world standards. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

And so it is that the tide of migrants – India’s urban population grew at 31.8% in the 10 years between 2001 and 2011, both census years, while the rural population grew at 12.18% and the overall national population growth rate was 17.64% with the difference between all three figures illustrating in one short equation the strength of the urbanisation project – is essential for the provision of cheap labour to the services sector for that higher economic strata upon whom the larger share of the GDP growth burden rests, the middle class.

And so the picture clears, for it is in maintaining and adding to the numbers of the middle class – no troublesome poverty lines here whose interpretations may arrest the impulse to consume – that the growth of India’s GDP relies. By the end of the first confused decade following the liberalisation of India’s economy, in the late-1990s, the arrant new ideology that posited the need for a demographic shift from panchayat to urban ward found supporters at home and outside (in the circles of the multi-lateral development lending institutions particularly, which our senior administrators and functionaries were lured into through fellowships and secondments). Until 10 years ago, it was still being said in government circles that India’s pace of urbanisation was only modest by world standards (said in the same off-the-cuff manner that explains our per capita carbon dioxide emissions as being well under the global average).

In 2005, India had 41 urban areas with populations of a million and more while China had 95 – in 2015 the number of our cities which will have at least a million will be more than 60. Hence the need to turn a comfortable question into a profoundly irritating one: instead of ‘let us mark the slums as being those areas of a city or town in which the poor live’ we choose ‘let us mark the poor along as many axes as we citizens can think of and find the households – in slum or cooperative housing society or condominium – that are deprived by our own measures’. The result of making such a choice would be to halt the patronymic practiced by the state (and its private sector assistants) under many different guises.

Whether urban residents in our towns and cities will bestir themselves to organise and claim such self-determination is a forecast difficult to attempt for a complex system such as a ward, in which issues of class and economic status have as much to do with group choices as the level of political control of ward committees and the participation of urban councillors, the grip of land and water mafias, the degree to which state programmes have actually bettered household lives or sharpened divisions.

It is probably still not a dilemma, provided there is re-education enough and awareness enough of the perils of continuing to inject ‘services’ and ‘infrastructure’ into communities which for over a generation have experienced rising levels of economic stress. At a more base level – for sociological concerns trouble industry even less, in general, than environmental concerns do – India’s business associations are doing their best to ensure that the urbanisation project continues. The three large associations – Assocham, CII and FICCI (and their partners in states) – agree that India’s urban population will grow, occupying 40% of the total population 15 years from now.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

Bharat and its billionaires

Several times a year, one money-minded organisation or another publishes a ‘rich list’. On this list are the names of the extraordinarily wealthy, the billionaires. Such a list is compiled by Forbes magazine. In this year’s list of billionaires, there are 90 Indians.

Several times a year, one money-minded organisation or another publishes a ‘rich list’. On this list are the names of the extraordinarily wealthy, the billionaires. Such a list is compiled by Forbes magazine. In this year’s list of billionaires, there are 90 Indians.

Perhaps it is the largest contingent of Indians on this list ever, perhaps their wealth is greater, singly and together, than ever before, perhaps the space below them (the almost-billionaires) is more crowded than ever. What must be of concern to us is the inequality that such a list represents. In the first two, perhaps three, Five Year Plans, cautions were expressed that the income (or wealth) multiple between the farmer and the labourer on the one hand and the entrepreneur or skilled manager on the other should not exceed 1 to 10.

In practice it was quite different, but the differences of the early 1990s – which is when economic liberalisation took hold in India – are microscopic compared to those of today. What’s more, the astronomically large differences in income/wealth of 2015 are actually celebrated as being evidence of India’s economic superpowerdom.

The current per capita national income is 88,533 rupees and it will take, as my disturbing panel of comparisons shows, the combined incomes of 677,713 such earners to equal the wealth of the 90th on the Forbes list of Indian billionaires. Likewise, there are six on the list of 90 with median incomes, and a median income is Rs 11.616 crore, which is equal to the entire Central Government budget outlay for agriculture (and allied activities) for 2015-16.

The discordant anthem of urban missions

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here and this is part two:

The ‘help’ of that period, envisioned as a light leg-up accompanied by informal encouragement, has become instead an industry of empowerment. There are “bank linkages for neutral loans to meet the credit needs of the urban poor”, the formation of corps of “resource organisations to be engaged to facilitate the formation of self-help groups and their development”, there are technical parameters to set so that “quality of services is not compromised”.

The ‘help’ of that period, envisioned as a light leg-up accompanied by informal encouragement, has become instead an industry of empowerment. There are “bank linkages for neutral loans to meet the credit needs of the urban poor”, the formation of corps of “resource organisations to be engaged to facilitate the formation of self-help groups and their development”, there are technical parameters to set so that “quality of services is not compromised”.

Financial literacy – of the unhoused, the misnourished, the chronically underemployed, the single-female-headed families, the uninsurable parents and dependents, the uncounted – is essential so that ‘no frills’ savings accounts can be opened (the gateway to a noxious web of intrusive micro-payment schemata: life, health, pension, consumer goods). Such a brand of functional literacy is to be dispensed by city livelihoods centres which will “bridge the gap between demand and supply of the goods and services produced by the urban poor” and who will then, thus armed, “access information and business support services which would otherwise not be affordable or accessible by them”. So runs the anthem of the National Urban Livelihoods Mission, the able assistant of the national urban mission and its successor-in-the-wings, the Rajiv Awas Yojana.

The existence of the ‘urban poor’ is what provides the legitimacy (howsoever constructed) that the central government, state governments, public and joint sector housing and infrastructure corporations, and a colourful constellation of ancillaries need to execute the urbanisation of India project. Lost in the debate over methodologies to find in the old and new bastis the deserving chronically poor and the merely ‘service deprived’ are the many aspects of poverty in cities, a number of which afflict the upper strata of the middle classes (well housed, overprovided for by a plethora of services, banked to a surfeit) just as much as they do the daily wage earners who commute from their slums in search of at least the six rupees they must pay out of every 10 so that their families have enough to eat for that day.

These deprivations are not accounted for nor even discussed as potential dimensions along which to measure the lives of urban citizens, poor or not, by the agencies that give us our only authoritative references for our citizens and the manner in which they live, or are forced to live: the Census of India, the National Sample Survey Office (of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation), the municipal corporations of larger cities, the ministries of health, of environment, and the ministry most directly concerned with urban populations, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

These deprivations are not accounted for nor even discussed as potential dimensions along which to measure the lives of urban citizens, poor or not, by the agencies that give us our only authoritative references for our citizens and the manner in which they live, or are forced to live: the Census of India, the National Sample Survey Office (of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation), the municipal corporations of larger cities, the ministries of health, of environment, and the ministry most directly concerned with urban populations, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

Exposure to pollution in concentrations that alarms the World Health Organisation, the absence of green spaces in wards, a level of ambient noise high enough to induce stress by itself, the weekly or monthly reconciling of irregular income (at any scale) versus the inflation that determines all costs of urban living – these are but a few of the many aspects under which a household or an individual can be ‘poor’. Income and food calorie poverty – which have been the measures to judge a household’s position in relation to a line of minimum adequacy – are but two of many interlinked aspects that govern a standard of living which every government promises to raise.

This catechism was repeated when the Sixteenth Lok Sabha began its work, and President Pranab Mukherjee mentioned in his address to the body a common habitat minimum for the 75th year of Indian Independence, which will come in 2022 (at a time when the many vacuous ‘2020 vision documents’ produced during the last decade by every ministry will have neither currency nor remit). Housing for all, Mukherjee assured the Lok Sabha, delivered through the agency of city-building – “100 cities focused on specialised domains and equipped with world-class amenities”; and “every family will have a pucca house with water connection, toilet facilities, 24×7 electricity supply and access”.

That is why, although concerned academicians and veteran NGO karyakartas will exchange prickly criticisms concerning the use in urban study of NSSO first stage units or the use of Census of India enumeration blocks, it is self-determination in the urban context that matters to a degree somewhat greater than the means we choose to use to describe that context. From the time of the ‘approach’ discussions to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07) – which is when the notion, till that time regarded as experimental, that the government can step away without guilt from its old role of providing for the poor in favour of the private sector – the dogma of growth of GDP has included rapid urbanisation.

That is why, although concerned academicians and veteran NGO karyakartas will exchange prickly criticisms concerning the use in urban study of NSSO first stage units or the use of Census of India enumeration blocks, it is self-determination in the urban context that matters to a degree somewhat greater than the means we choose to use to describe that context. From the time of the ‘approach’ discussions to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07) – which is when the notion, till that time regarded as experimental, that the government can step away without guilt from its old role of providing for the poor in favour of the private sector – the dogma of growth of GDP has included rapid urbanisation.

That such GDP growth – setting aside the crippling ecological and social costs which our administrative technorati, for all their ‘progressive’ credentials, do not bring themselves to publicly recognise – is deeply polarising and is especially so in cities is not a matter discussed in any of the 948 city development plans (1,515 infrastructure and housing projects) of the JNNURM. From then on, the seeking and finding of distinctions as they exist within the residential wards of towns and cities has been treated as heretical.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

Sizing up city life

Close ranks of tall residential towers signal a new township on the outskirts of Beijing, P R China.

Some two years ago, it was calculated, the world firmly entered the urban age, for the available evidence pointed to a startling truth: more people now live in cities than outside them. The balance between urban and rural populations differs between countries, at times considerably. Chad and Congo have about the same number of people living in cities, 2.95 million and 2.96, but these urban populations are 22% of the total population for Chad and 65% of the total population for Congo.

Overall, the balance between urban and rural populations is thought, conventionally, to directly describe whether a country is likely to be in the high income or low income groups of countries. The Department of Economic and Social Affairs – a specialist agency of the United Nations – entrusts such calculations to its Population Division whose ‘World Urbanization Prospects’ found, in its 2014 revision, that the proportion of urban populations for high income countries was 80% while that for low income countries was 30%. This seems to lend weight to the conventional wisdom that it is cities that galvanise the creation of the sort of wealth which gross domestic product (GDP) growth depends on.

Cities are seen to harbour dynamism and vitality. For those who live in such cities, this is largely true. Residents of cities like Seoul (Korea), Lima (Peru), Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad (all India), Bogotá (Colombia), Nagoya (Japan), Johannesburg (South Africa), Bangkok (Thailand) and Chicago (USA) are very likely to agree that living and working in their respective cities has brought tham prosperity, and are less likely to ponder about this group of cities being the top ten in the world with populations under 10 million in 2014 (there are 28 cities worldwide with populations of at least 10 million).

There is however another aspect to the formation of cities. In 1927, the film Metropolis, conceived by Fritz Lang and delivered as an artfully stylised cinematic message, described the strains and dangers of the power that cities had already come to have over their residents. For Metropolis was a futuristic city where a cultured utopia existed above a bleak underworld populated by mistreated workers. Just over 50 years later, another film, Blade Runner (1982), blended science fiction with a disturbing portrait of a dystopian and dangerous cityscape that was both gigantic and technology-centric, through which the human element struggled to find meaning.

There is however another aspect to the formation of cities. In 1927, the film Metropolis, conceived by Fritz Lang and delivered as an artfully stylised cinematic message, described the strains and dangers of the power that cities had already come to have over their residents. For Metropolis was a futuristic city where a cultured utopia existed above a bleak underworld populated by mistreated workers. Just over 50 years later, another film, Blade Runner (1982), blended science fiction with a disturbing portrait of a dystopian and dangerous cityscape that was both gigantic and technology-centric, through which the human element struggled to find meaning.

If Metropolis represented the post-industrial revolution European cityscape, then Blade Runner depicted the flagship of what has been called the Asian century, for its mesmerising and frightening urban backdrop was Tokyo then, and could well be China now. The Japanese capital remains in 2014 the world’s largest city with an agglomeration of 38 million inhabitants, followed by New Delhi with 25 million, Shanghai with 23 million, and Mexico City, Mumbai and São Paulo, each with around 21 million inhabitants. By 2030, so the projections say, the world will have 41 mega-cities of more than 10 million inhabitants.

For all their celebrated roles as centres of wealth, innovation and culture, these mega-cities and their smaller counterparts exert dreadful pressures on natural resources and the environment. These are already either unmanageable or uneconomical to deal with, more so in the rapidly growing urban centres of Asia and Africa. Despite the lengthening list of urban problems – most caused by rural folk flocking to cities faster than urban governance structures can cope with existing needs – demographers foresee that today’s trend will add 2.5 billion people to the world’s urban population by 2050. India, China and Nigeria are together expected to account for 37% of the projected growth of the world’s urban population between this year and 2050. It is there that the idea of the city, which so fascinated Fritz Lang, will be sorely tested.

The industry of urban empowerment

The latest issue of the occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue is titled ‘The industry of ’empowerment’ in which I have described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ’empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts; here is part one:

2015 will be the tenth year of India’s largest urban recalibration programme. That decadal anniversary will, for one section of our society, be used as proof that new infrastructure in cities has lowered poverty, that new housing has raised the standard of living for those who need it most, that urban rebuilding capital is focused better through such measures and, because of these and like reasons, that giant programmes such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) must continue. With or without the name of India’s first prime minister applied to the mission (itself a noun used liberally to impel urgency into a programme), it will continue, enriched with finance and technology.

2015 will be the tenth year of India’s largest urban recalibration programme. That decadal anniversary will, for one section of our society, be used as proof that new infrastructure in cities has lowered poverty, that new housing has raised the standard of living for those who need it most, that urban rebuilding capital is focused better through such measures and, because of these and like reasons, that giant programmes such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) must continue. With or without the name of India’s first prime minister applied to the mission (itself a noun used liberally to impel urgency into a programme), it will continue, enriched with finance and technology.

The JNNURM, a year from now, will be the foremost symbol amongst several that signal to some 415 million Indians (city-dwellers all, for that will be the approximate urban population a year from now) why city life and city lights are what matter.

For another section of society, less inclined because of experience with administrations indifferent or venal, life in India’s (and Bharat’s) 7,935 towns goes on minus the pithy optimism of governments and their supporters in industry and finance. The promise of higher monthly household incomes is somehow expected to compensate for the grinding travails that urban life in India brings, and it is a promise documented inside 50 years of gazettes and government orders, countless circulars and memoranda, hundreds of reports by committees high-powered and technical.

Still the number of villages that are transformed, statistically and temporally into towns (census and statutory) grows from one census to another (and in between), and still the urban agglomerations — some sprawling uncaring from one district into another, consuming agricultural land and watershed — expand, for the instruction of the market is that it is this process of gathering citizens that leads to the growth of gross domestic product (GDP), the prime mechanic in the alleviation of poverty, whose workings in cities are much studied but elude definition.

The density of programmes and schemes that envelop urban-dwellers — those whose households hover above or below a poverty line, those whose informal wage earnings are insufficient to maintain a crumbling housing board tenement — is confusing, inside administrations as much as outside them. The thicket of entitlements and provisions that have been designed, so we are told, to ensure the provision of ‘services’ and ‘amenities’, confounds navigation.

The density of programmes and schemes that envelop urban-dwellers — those whose households hover above or below a poverty line, those whose informal wage earnings are insufficient to maintain a crumbling housing board tenement — is confusing, inside administrations as much as outside them. The thicket of entitlements and provisions that have been designed, so we are told, to ensure the provision of ‘services’ and ‘amenities’, confounds navigation.

There are economically weaker sections and lower income groups to plan for (provided they remain weaker and lower); there are ‘integrated, reform-driven, fast-track’ sub-missions and components that are aimed at increasing the effectiveness and accountability of urban local bodies, all as part of the ‘Urban Infrastructure and Governance’ standards to be applied under the Urban Infrastructure Development Schemes for Small and Medium Towns (UIDSSMT, which defies any attempt to make acronyms pronounceable) in 65 mission cities.

Prominent within this grand and swelling orchestra of urbanisation are some of the star creations of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty-Alleviation. There is the Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP) and the Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP) and these round up the gamut of concepts proffered by the urban planning dogma of our times: “integrated development of slums through projects”, “providing for shelter, basic services and other related civic amenities with a view towards providing utilities to the urban poor”, “key pro-poor reforms that include the implementation of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act”, and “delivery through convergence of other already existing universal services”.

There are public-private partnership templates to guide business (and the odd social entrepreneurship) through this new topology; there are special purpose vehicles formed that mendaciously grey the distinctions between bond and financial markets and the greater public good, but which we are assured will function as the money backstop for public administrations whose clerks peer befuddled at slick online reporting formats (transparency at work, round the clock, accessible through apps on the beneficiaries’ tablet phones).

There is ‘inclusion’ — that most essential salt that flavours the substance of governance today — to be found in every direction. There are plenty of beneficiaries to enlist in this urban social re-engineering that is proceeding on a scale and pace unthinkable a generation ago in our towns (public sector housing colonies and waiting lists for scooters), when ‘income inequality’ was an uncommon topic of discussion and ‘gini coefficient’ had yet to become a society’s alarm bell. The new cadre of GDP engineers is well schooled in the language of human rights and normative justice, and so we have ‘Social Mobilisation and Institution Development’ which attends ‘Employment through Skills Training and Placement’, both of which facilitate ’empowerment, financial self-reliance, and participation and access to government’.

There is ‘inclusion’ — that most essential salt that flavours the substance of governance today — to be found in every direction. There are plenty of beneficiaries to enlist in this urban social re-engineering that is proceeding on a scale and pace unthinkable a generation ago in our towns (public sector housing colonies and waiting lists for scooters), when ‘income inequality’ was an uncommon topic of discussion and ‘gini coefficient’ had yet to become a society’s alarm bell. The new cadre of GDP engineers is well schooled in the language of human rights and normative justice, and so we have ‘Social Mobilisation and Institution Development’ which attends ‘Employment through Skills Training and Placement’, both of which facilitate ’empowerment, financial self-reliance, and participation and access to government’.

About 30 years ago, The State of India’s Environment 1984-85 (Centre for Science and Environment) noted in a tone of cautious optimism that “planners are beginning to realise that squatters are economically valuable citizens who add to the gross national product by constructing their own shelter, no matter how makeshift, which saves the government a considerable amount of money”. That was a time when governments still sought to save money and the CSE report went on to explain that squatters “are upwardly mobile citizens in search of economic opportunity and have demonstrated high levels of enterprise, tenacity, and ability to suffer acute hardships; that the informal sector in which a majority of the slum-dwellers are economically active contributes significantly to the city’s overall economic growth; and that they should be helped and not hindered”.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ’empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

What we know and don’t about the true price of dal

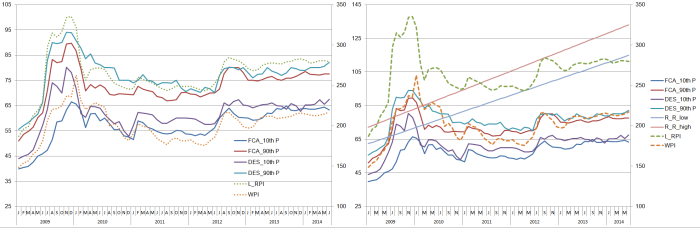

If you look at only the official account (left), the price of dal has been comfortable, but the consumer experience (right) tells a quite different story.

How urgently our national food price measuring methods need a complete overhaul is best shown with the example of a staple everyone is familiar with: arhar or tur dal.

Price indexes or indices are useful because they help us view the change in the price of a particular food staple over time, not the price itself, but change in price when taken from a base year or month. Price records are useful because they log the price (per kilo for retail consumption) of a food staple in a week or month.

The three ministries concerned with food prices update their indices or actual price reports every month or week. These are: the Department of Consumer Affairs of the Ministry of Food and Consumer Affairs, the Directorate of Economics and Statistics of the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation of the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Labour Bureau of the Ministry of Labour. In addition, there is the wholesale price index prepared by the Office of the Economic Adviser, Ministry of Commerce.

Usually, movements and trends in these indices and price logs are examined by themselves, and conclusions are drawn about whether the price of a food staple has been held steady or is rising steadily or is rising seasonally and also annually (we never see prices and trends going downwards).

Usually, movements and trends in these indices and price logs are examined by themselves, and conclusions are drawn about whether the price of a food staple has been held steady or is rising steadily or is rising seasonally and also annually (we never see prices and trends going downwards).

But this is not enough. We need also to examine whether these indices and price logs are describing what they are designed to in the same manner and – very much more important – whether their descriptions are reasonable or not.

In the two chart panels, I have plotted the descriptions for arhar/tur dal from several sources together. The left chart has solid coloured price lines from the Department of Consumer Affairs and from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics. Each has two lines, the higher at the 90th percentile and the lower at the 10th percentile of all monthly prices logged from 2009 January until 2014 June. The two dashed lines are indices – the wholesale price index for arhar/tur and the Labour Bureau’s retail price index for arhar/tur over the same period. The price logs are plotted against the left index and the price indices are plotted against the right index.

Between the two indices the WPI for arhar appears lower than the Labour Bureau index, but that has only to do with a difference base period. The overall pattern they describe is the same. The two sets of price logs shows the two different levels for the 90th and 10th percentiles – in both cases the prices recorded by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics are higher than those recorded by the Department of Consumer Affairs. However they all follow a similar pattern over the 66 months illustrated here.

And so to the question: how true is what these indices and price logs are describing?

And so to the question: how true is what these indices and price logs are describing?

The answer is in the right chart. Here, two more lines are seen. These are both ascending relatively evenly over the 66 months, one at a slightly steeper rate. These I have called the ‘real retail’ price lines, one low and the other high. They describe the prices paid by urban consumers for a kilogram of arhar/tur dal based on what has been charged by ordinary retail outlets in towns and cities, with the price readings collected informally. They have also been ‘straightened’ by applying a 12%-14% true inflation that has been experienced by urban food consumers over these 66 months.

The effect, as you can see, is startling. The ‘real retail’ price lines explain why the consumption of pulses has been dropping and continues to drop especially amongst urban households whose livelihoods depend on multiple informal jobs. At Rs 90 to Rs 110 per kilogram, this dal (like other pulses) is almost beyond reach. At Rs 120 to Rs 130 per kilogram – these are levels that began to be recorded by consumers, but not consistently by the government price monitoring agencies, even two years ago – the dal can be consumed only by the upper strata of the urban middle class.

The question that immediately arises is: why is the real food price inflation being experienced by consumers not reflected in the official food price logs and indices? I will take up this question in the next posting.