Posts Tagged ‘development’

The persistent fiction of independent India

Today morning, tens of millions of schoolchildren all over India were ordered to attend what is called flag hoisting. The national flag of India is run up a flagpole set in front of, or near, many thousands of schools, and a group of school functionaries pull a rope that sets the flag up atop the pole. The national anthem is played, several speeches are delivered, often including one or two (if the schoolchildren have ill luck) by a local political bigwig or member of the state assembly. The students may present a skit or two, in which they have been drilled during the preceding weeks, and then they disperse.

This has been the pattern to which Independence Day in India is marked and celebrated for as long as I remember. When the television era began, the live telecast of the indepdence day parade in New Delhi became a much looked forward to event. The parade has had the same ingredients for decades. Contingents from the three armed forces march, various sorts of wheeled and motorised weaponry drives slowly past, the President of India and as many members of Parliament as can be mustered sit in the VIP boxes to desultorily watch the parade. A number of what are called ‘floats’, tableaux mounted on lorries, are driven past, apparently representing the states of India or some theme.

And so it has gone, year after miserable year. The fiction of freedom is renewed annually by the independence day parade, which long ago became a collective ritual choreographed and managed. Like many invented rituals, this one applies a cosmetic veneer. Perhaps in the 1970s and 1980s, there were still Indians who saw the ritual for what it is, and who were aware of the forces that encircled what was presented to all of us as the “sovereign republic of India”.

Today I see very little indeed of that awareness remaining. The great mass of the Indian middle class has been distracted from such reflection by the baubles of “development” (‘vikas’ in Hindi) which has become an end in itself, and which is given any meaning that suits the Indian agents of those encircling forces. If – so the fiction goes – the last remnant of the colonial power whcih had ruled India withdrew on 14 August 1947, then we should, in a matter of no more than two generations, have had a country very different – very different indeed – from the one we see today called India.

What have we today in this colonised territory called India?

The ideologies about knowledge

The few paragraphs that follow are taken from my recent article for the TERI (The Energy and Resources Institute) magazine, Terragreen. Published in the 2016 May issue, the article links what we often call traditional knowledge with the ways in which we understand ecology and the ways in which we are defining ‘sustainable development’.

Sustainable development has today become a commonly used term, yet it describes a concept that is still being considered by different kinds of societies, by each in a manner of its choosing. This has happened because while historically how societies grew to be ‘developed’ was a process that took a variety of pathways, today the prescribed pathway to the ‘modern’ scarcely changes from one country to another.

Sustainable development has today become a commonly used term, yet it describes a concept that is still being considered by different kinds of societies, by each in a manner of its choosing. This has happened because while historically how societies grew to be ‘developed’ was a process that took a variety of pathways, today the prescribed pathway to the ‘modern’ scarcely changes from one country to another.

Hence culturally what these societies have considered as being ‘sustainable’ behaviour – each according to its ecological context – is being replaced by a prescribed template in which interpretations are discouraged. Such a regime of prescription has led only to the obscuring of the many different kinds of needs felt by communities that desire a ‘development’ that makes cultural sense, but also of the kinds of knowledge which will allow that ‘development’ to be sustainable.

Some of this knowledge we can readily see. To employ labels whose origin is western, these streams of knowledge and practice are called traditional knowledge, intangible cultural heritage, indigenous wisdom, folk traditions, or indigenous and local knowledge. These labels help serve as gateways to understand both the ideas, ‘development’ and ‘sustainable’. It is well that they do for today, very much more conspicuously than 20 years earlier, there is a concern for declining biodiversity, about the pace and direction of global environmental change, a concern over the unsustainable human impact on the biosphere and the diminishing of community identity.

There is widespread acknowledgement of the urgency of the situation – this is perceived across cultures, geographical scales (that is, from local units such as a village, to national governments), and knowledge systems (and this includes both formal and non-formal ways of recognising these systems). The need for such a new dialogue on the situation is expressed in several global science-policy initiatives, both older and recent, such as the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) which is now 22 years old, and the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), whose first authoritative reports became available in 2015.

Development whose sustainability is defined locally and implemented locally means that the ‘investment’, ‘technology’ and ‘innovation’ (terms that have become popular to describe development efforts) comes from the people themselves. Many diverse agencies at this level – civil society, youth groups, vocational networks, small philanthropies – assist such development and provide the capacities needed. This is the level at which the greatest reliance on cultural approaches takes place, endogenously.

In domains such as traditional medicine, forestry, the conservation of biodiversity, the protection of wetlands, it is practitioners of intangible cultural heritage and bearers of traditional knowledge, together with the communities to which they belong, who observe and interpret phenomena at scales much finer than formal scientists are familiar with. Besides, they possess the ability to draw upon considerable temporal depth in their observations. For the scientific world, such observations are invaluable contributions that advance our knowledge about climate change. For the local world, indigenous knowledge and cultural practices are the means with which the effects of climate change are negotiated so that livelihoods are maintained, ritual and cultivation continue, and survival remains meaningful.

To localise and humanise India’s urban project

Cities and towns have outdated and inadequate master plans that are unable to address the needs of inhabitants. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here, part two is found here, part three is here and this is part four:

The reason they pursue this objective in so predatory a manner is the potential of GDP being concentrated – their guides, the international management consulting companies (such as McKinsey, PriceWaterhouse Coopers, Deloitte, Ernst and Young, Accenture and so on), have determined India’s unique selling proposition to the world for the first half of the 21st century. It runs like this: “Employment opportunities in urban cities will prove to be a catalyst for economic growth, creating 70% of net new jobs while contributing in excess of 70% to India’s GDP.” Naturally, the steps required to ensure such a concentration of people and wealth-making capacity include building new urban infrastructure (and rebuilding what exists, regardless of whether it serves the ward populations or not).

“Employment opportunities in urban cities will prove to be a catalyst for economic growth” is the usual excuse given for the sort of built superscale seen in this metro suburb. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

The sums being floated today for achieving this camouflaged subjugation of urban populations defy common sense, for any number between Rs 5 million crore and Rs 7 million crore is being proposed, since an “investment outlay will create a huge demand in various core and ancillary sectors causing a multiplier effect through inter-linkages between 254 industries including those in infrastructure, logistics and modern retail… it will help promote social stability and economic equality through all-round development of urban economic centres and shall improve synergies between urban and rural centres”.

Tiers of overlapping programmes and a maze of controls via agencies shaded in sombre government hues to bright private sector colours are already well assembled and provided governance fiat to realise this ‘transformation’, as every government since the Tenth Plan has called it (the present new government included). For all the academic originality claimed by a host of new urban planning and habitat research institutes in India (many with faculty active in the United Nations circuits that gravely discuss the fate of cities; for we have spawned a new brigade of Indian – though not Bharatiya – urban studies brahmins adept at deconstructing the city but ignorant of such essentials as ward-level food demand), city planning remains a signal failure.

Typically, democratisation and self-determination is permitted only in controlled conditions. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

Other than the metropolitan cities and a small clutch of others (thanks to the efforts of a few administrative individuals who valued humanism above GDP), cities and towns have outdated and inadequate master plans that are unable to address the needs of city inhabitants in general (and of migrants in particular). These plans, where they exist, are technically prepared and bureaucratically envisioned with little involvement of citizens, and so the instruments of exclusion have been successfully transferred to the new frameworks that determine city-building in India.

Democratisation and self-determination is permitted only in controlled conditions and with ‘deliverables’ and ‘outcomes’ attached – organic ward committees and residents groups that have not influenced the vision and text of a city master plan have even less scope today to do so inside the maze of technocratic and finance-heavy social re-engineering represented by the JNNURM, RAY, UIDSSMT, BSUP, IHSDP and NULM and all their efficiently bristling sub-components. The rights of inhabitants to a comfortable standard of life that does not disturb environmental limits, to adequate and affordable housing, to safe and reliable water and sanitation, to holistic education and healthcare, and most of all the right to alter their habitats and processes of administration according to their needs, all are circumscribed by outside agencies.

Managed socialisation in our cities and towns must give way to organic groups. Photo: Rahul Goswami (2013)

It is not too late to find remedies and corrections. “As long as the machinery is the same, if we are simply depending on the idealism of the men at the helm, we are running a grave risk. The Indian genius has ever been to create organisations which are impersonal and are self-acting. Mere socialisation of the functions will not solve our problem.” So J C Kumarappa had advised (the Kumarappa Papers, 1939-46) about 80 years ago, advice that is as sensible in the bastis of today as it was to the artisans and craftspeople of his era.

For the managed socialisation of the urbanisation project to give way to organic groups working to build the beginnings of simpler ways in their communities will require recognition of these elements of independence now. It is the localisation of our towns and cities that can provide a base for reconstruction when existing and planned urban systems fail. Today some of these are finding ‘swadeshi’ within a consumer-capitalist society that sees them as EWS, LIG and migrants, and it is their stories that must guide urban India.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

No Shri Javadekar, India won’t gamble with carbon

Coal will account for much of India’s energy for another generation. How does the BJP calculate its ‘value’ at international climate talks? Image: PTI/Deccan Chronicle

There is a message New Delhi’s top bureaucrats must listen to and understand, for it is they who advise the ministers. The message has to do with climate change and India’s responsibilities, within our country and outside it. This is the substance of the message:

1. The Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance government must stop treating the factors that contribute to climate change as commodities that can be bartered or traded. This has been the attitude of this government since it was formed in May 2014 – an attitude that says, in sum, ‘we will pursue whatever GDP goals we like and never mind the climate cost’, and that if such a pursuit is not to the liking of the Western industrialised world, India must be compensated.

2. Rising GDP is not the measure of a country and it is not the measure of India and Bharat. The consequences of pursuing rising GDP (which does not mean better overall incomes or better standards of living) have been plain to see for the better part of 25 years since the process of liberalisation began. Some of these consequences are visible in the form of a degraded natural environment, cities choked in pollution, the rapid rise of non-communicable diseases, the economic displacement of large rural populations. All these consequences have dimensions that deepen the impacts of climate change within our country.

3. There are no ‘terms of trade’ concerning climate change and its factors. There is no deal to jockey for in climate negotiations between a narrow and outdated idea of GDP-centred ‘development’ and monetary compensation. The government of India is not a broking agency to bet a carbon-intensive future for India against the willingness of Western countries to pay in order to halt such a future. This is not a carbon casino and the NDA-BJP government must immediately stop behaving as if it is.

The environment minister, Prakash Javadekar, has twice in March 2015 said exactly this: we will go ahead and pollute all we like in the pursuit of our GDP dream – but if you (world) prefer us not to, give us lots of money as compensation. Such an attitude and such statements are to be condemned. That Javadekar has made such a statement is bad enough, but I find it deeply worrying that a statement like this may reflect a view within the NDA-BJP government that all levers of governance are in fact monetary ones that can be bet, like commodities can, against political positions at home and abroad. If so, this is a very serious error being made by the central government and its advisers.

The environment minister, Prakash Javadekar, has twice in March 2015 said exactly this: we will go ahead and pollute all we like in the pursuit of our GDP dream – but if you (world) prefer us not to, give us lots of money as compensation. Such an attitude and such statements are to be condemned. That Javadekar has made such a statement is bad enough, but I find it deeply worrying that a statement like this may reflect a view within the NDA-BJP government that all levers of governance are in fact monetary ones that can be bet, like commodities can, against political positions at home and abroad. If so, this is a very serious error being made by the central government and its advisers.

Javadekar has most recently made this stand clear in an interview with a foreign news agency. In this interview (which was published on 26 March 2015), Javadekar is reported to have said: “The world has to decide what they want. Every climate action has a cost.” Worse still, Javadekar said India’s government is considering the presentation of a deal – one set of commitments based on internal funding to control emissions, and a second set, with deeper emissions cuts, funded by foreign money.

Earlier in March, during the Fifteenth Session of the African Ministerial Conference on Environment (in Cairo, Egypt), Javadekar had said: “There has to be equitable sharing of the carbon space. The developed world which has occupied large carbon space today must vacate the space to accommodate developing and emerging economies.” He also said: “The right to development has to be respected while collectively moving towards greener growth trajectory.”

Such statements are by themselves alarming. If they also represent a more widespread view within the Indian government that the consequences of the country following a ‘development’ path can be parleyed into large sums of money, then it indicates a much more serious problem. The UNFCCC-led climate change negotiations are infirm, riddled with contradictions, a hotbed of international politics and are manipulated by finance and technology lobbies.

It remains on paper an inter-governmental arrangement and it is one that India is a part of and party to. Under such circumstances, our country must do all it can to uphold moral action and thinking that is grounded in social and environmental justice. The so-called Annex 1 countries have all failed to do so, and instead have used the UNFCCC and all its associated mechanisms as tools to further industry and foreign policy interests.

It remains on paper an inter-governmental arrangement and it is one that India is a part of and party to. Under such circumstances, our country must do all it can to uphold moral action and thinking that is grounded in social and environmental justice. The so-called Annex 1 countries have all failed to do so, and instead have used the UNFCCC and all its associated mechanisms as tools to further industry and foreign policy interests.

It is not in India’s nature and it is not in India’s character to to the same, but Javadekar’s statement and the government of India’s approach – now made visible by this statement – threatens to place it in the same group of countries. This is a crass misrepresentation of India. According to the available data, India in 2013 emitted 2,407 million tons of CO2 (the third largest emitter behind the USA and China). In our South Asian region, this is 8.9 times the combined emissions of our eight neighbours (Pakistan, 165; Bangladesh, 65; Sri Lanka, 15; Myanmar, 10; Afghanistan, 9.4; Nepal, 4.3; Maldives, 1.3; Bhutan, 0.7).

When we speak internationally of being responsible we must first be responsible at home and to our neighbours. Javadekar’s is an irresponsible statement, and is grossly so. Future emissions are not and must never be treated as or suggested as being a futures commodity that can attract a money premium. Nor is it a bargaining chip in a carbon casino world. The government of India must clearly and plainly retract these statements immediately.

Note – according to the UNFCCC documentation, “India communicated that it will endeavour to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 20-25 per cent by 2020 compared with the 2005 level. It added that emissions from the agriculture sector would not form part of the assessment of its emissions intensity.”

“India stated that the proposed domestic actions are voluntary in nature and will not have a legally binding character. It added that these actions will be implemented in accordance with the provisions of relevant national legislation and policies, as well as the principles and provisions of the Convention.”

India’s writing of the urbanised middle-class symphony

The maintaining of and adding to the numbers of the middle class is what the growth of India’s GDP relies upon. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here, part two is found here, and this is part three:

A small matrix of classifications is the reason for such obtuseness, which any kirana shop owner and his speedy delivery boys could quickly debunk. As with the viewing of ‘poverty’ so too the consideration of an income level as the passport between economic strata (or classes) in a city: the Ministry of Housing follows the classification that a household whose income is up to Rs 5,000 a month is pigeon-holed as belonging to the economically weaker section while another whose income is Rs 5,001 and above up to Rs 10,000 is similarly treated as lower income group.

Committees and panels studying our urban condition are enjoined not to stray outside these markers if they want their reports to find official audiences, and so they do, as did the work (in 2012) of the Technical Group on Urban Housing Shortage over the Twelfth Plan period (which is 2012-17). Central trade unions were already at the time stridently demanding that Rs 10,000 be the national minimum wage, and stating that their calculation was already conservative (so it was, for the rise in the prices of food staples had begun two years earlier).

The contributions of those in the lower economic strata (not the ‘poor’ alone, however they are measured or miscounted) to the cities of India and the towns of Bharat, to the urban agglomerations and outgrowths (terms that conceal the entombment of hundreds of hectares of growing soil in cement and rubble so that more bastis may be accommodated), are only erratically recorded. When this is done, more often than not by an NGO, or a research institute (not necessarily on urban studies) or a more enlightened university programme, seldom do the findings make their way through the grimy corridors of the municipal councils and into recognition of the success or failure of urban policy.

Until 10 years ago, it was still being said in government circles that India’s pace of urbanisation was only ‘modest’ by world standards. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

And so it is that the tide of migrants – India’s urban population grew at 31.8% in the 10 years between 2001 and 2011, both census years, while the rural population grew at 12.18% and the overall national population growth rate was 17.64% with the difference between all three figures illustrating in one short equation the strength of the urbanisation project – is essential for the provision of cheap labour to the services sector for that higher economic strata upon whom the larger share of the GDP growth burden rests, the middle class.

And so the picture clears, for it is in maintaining and adding to the numbers of the middle class – no troublesome poverty lines here whose interpretations may arrest the impulse to consume – that the growth of India’s GDP relies. By the end of the first confused decade following the liberalisation of India’s economy, in the late-1990s, the arrant new ideology that posited the need for a demographic shift from panchayat to urban ward found supporters at home and outside (in the circles of the multi-lateral development lending institutions particularly, which our senior administrators and functionaries were lured into through fellowships and secondments). Until 10 years ago, it was still being said in government circles that India’s pace of urbanisation was only modest by world standards (said in the same off-the-cuff manner that explains our per capita carbon dioxide emissions as being well under the global average).

In 2005, India had 41 urban areas with populations of a million and more while China had 95 – in 2015 the number of our cities which will have at least a million will be more than 60. Hence the need to turn a comfortable question into a profoundly irritating one: instead of ‘let us mark the slums as being those areas of a city or town in which the poor live’ we choose ‘let us mark the poor along as many axes as we citizens can think of and find the households – in slum or cooperative housing society or condominium – that are deprived by our own measures’. The result of making such a choice would be to halt the patronymic practiced by the state (and its private sector assistants) under many different guises.

Whether urban residents in our towns and cities will bestir themselves to organise and claim such self-determination is a forecast difficult to attempt for a complex system such as a ward, in which issues of class and economic status have as much to do with group choices as the level of political control of ward committees and the participation of urban councillors, the grip of land and water mafias, the degree to which state programmes have actually bettered household lives or sharpened divisions.

It is probably still not a dilemma, provided there is re-education enough and awareness enough of the perils of continuing to inject ‘services’ and ‘infrastructure’ into communities which for over a generation have experienced rising levels of economic stress. At a more base level – for sociological concerns trouble industry even less, in general, than environmental concerns do – India’s business associations are doing their best to ensure that the urbanisation project continues. The three large associations – Assocham, CII and FICCI (and their partners in states) – agree that India’s urban population will grow, occupying 40% of the total population 15 years from now.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

A new agenda for India’s agriculture

Home, cattle, farming household and essential biomass in a hill village, Himachal Pradesh. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

Three weeks before the presenting of annual budget 2015-16 to the country (that is, us Bharatvaasis) and to the Parliament, the NDA-BJP government needs very much to recognise and respond sensibly to several truths. These are: that most Indian households and families are rural and agricultural, that the macro-economic fashion that has been followed since around 1990 elevates a uni-dimensional idea of economic ‘growth’ above all other considerations, and that several important factors both external and internal have rendered this idea of ‘growth’ obsolete.

Concerning the interaction of the three points – there are 90.2 million farming households households in Bharat – the analyst and commentator Devinder Sharma has reminded Arun Jaitley, Jayant Sinha, Rajiv Mehrishi, Arvind Subramanian, Ila Patnaik, H A C Prasad and other senior officials of the Finance Ministry that there is a continuing crisis which needs specific attention.

Sharma has outlined eleven points for the Ministry of Finance to take note of in its preparations for annual budget 2015-16 and I have summarised these points hereunder, and added four adjunct points to elaborate his very thoughtful advice.

Called ‘An 11-point agenda for resurrecting Indian agriculture and restoring the pride in farming’, Sharma has said: “Indian agriculture is faced with a terrible agrarian crisis. It is a crisis primarily of sustainability and economic viability. The severity of the crisis can be gauged from the spate of farm suicides. In the past 17 years, close to 3 lakh farmers reeling under mounting debt have preferred to commit suicide. Another 42% want to quit agriculture if given a choice. The spate of farmer suicide and the willingness of farmers to quit agriculture is a stark reminder of the grim crisis.”

Item 1. Providing a guaranteed assured monthly income to farmers. “Set up a National Farmers Income Commission which should compute the monthly income of a farm family depending upon his production and the geographical location of the farm.”

Item 2. No more Minimum Support Price (MSP) policy. This has historically been used to ask about its impact on food inflation. “Move from price policy to income policy. The income that a farmer earn should be de-linked from the price that his crops fetch in the market.”

Item 2.5. About 44% of agricultural households hold MGNREGA job cards. Among agricultural households, depending on the size of land held, non-farm income is significant. The need is to strengthen rural employment sources and income reliability as a major plank of local food security.

Item 3. Strengthen immediately the network of mandis (market yards) in all states and districts which provide farmers with a platform to sell their produce. “Leaving it to markets will result in distress sale.”

Fruit and vegetables being sorted in a village collection centre, Himachal Pradesh. Photo: Rahul Goswami 2014

Item 4. Provide a viable marketing network for fruits and vegetables (horticultural produce). “I see no reason why India cannot carve out a marketing chain (like the milk cooperatives) for fruits, vegetables and other farm commodities.”

Item 4.5. ‘Market’ does not mean ‘mandi’. The thrust of the ‘reform’ demanded in the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Acts is to “remove deterrent provisions” and “dismantle barriers to agriculture trade”. This effort will ruin smallholder farmers and must be halted.

Item 5. Cooperative farming must be encouraged including with legal support to make cooperatives more independent and effective. “Small cooperatives of organic farmers have done wonders” which be replicated for the rest of the crops.

Item 6. Villages must become self-reliant in agriculture and food security. “Shift the focus to local production, local procurement and local distribution” throughout the country for which the National Food Security Act needs amendment.

Item 7. Green Revolution areas are facing a crisis in sustainability. “With soil fertility devastated, water table plummeting and environment contaminated with chemical pesticides and fertiliser, the resulting impact on the entire food chain and human health is being increasingly felt.” We need a country-wide campaign to shift farming to non-pesticides management techniques.

Item 7.5. The agro-ecological approach to cultivation under decentralised planning (panchayat cluster) must be promoted. This has long been identified as the primary rural guide: “In the Indian development strategy, self-reliance has been conceptualised … in terms of building up domestic capabilities and reducing import dependence in strategic commodities” (from the Seventh Five Year Plan, 1985-90).

Item 8. Agriculture, dairy and forestry should be integrated. “Agricultural growth should not only be measured in terms of increase in foodgrain production but should be seen in the context of the village eco-system as a whole.”

Item 9. The government must not yield to pressure exerted via free trade agreements signed and stop food imports. “Importing food is importing unemployment.” The government must “not accept the European Union’s demand for opening up for dairy products and fruits/vegetables by reducing the import duties.”

Item 10. Climate change is affecting agriculture. Don’t look “at strategies only aimed at lessening the impact on agriculture and making farmers cope with the changing weather patterns, the focus should also be to limit greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.” Reduce chemical fertiliser/pesticides in farming.

Item 10.5. The area-production-yield metric for agriculture is as outdated as ‘GDP growth’ is to describe a country. By adopting the principles of responsible and ecologically sound self-reliance, the whole system demands of agriculture need to be assessed with district planning being incentivised towards organic cultivation (expressly banning GM/GE).

Item 11. Localise the storage for foodgrains. In 1979 under the ‘Save Food Campaign’ grain silos were to be set up in 50 places. Localised and locally-managed foodgrain storage must be at the top of the agenda.

This is an agriculture and food agenda for the NDA-BJP government, to guide the strategies and approaches so that India does not compromise its food self-sufficiency, self-reliance (swadeshi) and return our farming households to dignity and self-respect.

The discordant anthem of urban missions

The occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue has described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts – part one may be read here and this is part two:

The ‘help’ of that period, envisioned as a light leg-up accompanied by informal encouragement, has become instead an industry of empowerment. There are “bank linkages for neutral loans to meet the credit needs of the urban poor”, the formation of corps of “resource organisations to be engaged to facilitate the formation of self-help groups and their development”, there are technical parameters to set so that “quality of services is not compromised”.

The ‘help’ of that period, envisioned as a light leg-up accompanied by informal encouragement, has become instead an industry of empowerment. There are “bank linkages for neutral loans to meet the credit needs of the urban poor”, the formation of corps of “resource organisations to be engaged to facilitate the formation of self-help groups and their development”, there are technical parameters to set so that “quality of services is not compromised”.

Financial literacy – of the unhoused, the misnourished, the chronically underemployed, the single-female-headed families, the uninsurable parents and dependents, the uncounted – is essential so that ‘no frills’ savings accounts can be opened (the gateway to a noxious web of intrusive micro-payment schemata: life, health, pension, consumer goods). Such a brand of functional literacy is to be dispensed by city livelihoods centres which will “bridge the gap between demand and supply of the goods and services produced by the urban poor” and who will then, thus armed, “access information and business support services which would otherwise not be affordable or accessible by them”. So runs the anthem of the National Urban Livelihoods Mission, the able assistant of the national urban mission and its successor-in-the-wings, the Rajiv Awas Yojana.

The existence of the ‘urban poor’ is what provides the legitimacy (howsoever constructed) that the central government, state governments, public and joint sector housing and infrastructure corporations, and a colourful constellation of ancillaries need to execute the urbanisation of India project. Lost in the debate over methodologies to find in the old and new bastis the deserving chronically poor and the merely ‘service deprived’ are the many aspects of poverty in cities, a number of which afflict the upper strata of the middle classes (well housed, overprovided for by a plethora of services, banked to a surfeit) just as much as they do the daily wage earners who commute from their slums in search of at least the six rupees they must pay out of every 10 so that their families have enough to eat for that day.

These deprivations are not accounted for nor even discussed as potential dimensions along which to measure the lives of urban citizens, poor or not, by the agencies that give us our only authoritative references for our citizens and the manner in which they live, or are forced to live: the Census of India, the National Sample Survey Office (of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation), the municipal corporations of larger cities, the ministries of health, of environment, and the ministry most directly concerned with urban populations, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

These deprivations are not accounted for nor even discussed as potential dimensions along which to measure the lives of urban citizens, poor or not, by the agencies that give us our only authoritative references for our citizens and the manner in which they live, or are forced to live: the Census of India, the National Sample Survey Office (of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation), the municipal corporations of larger cities, the ministries of health, of environment, and the ministry most directly concerned with urban populations, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

Exposure to pollution in concentrations that alarms the World Health Organisation, the absence of green spaces in wards, a level of ambient noise high enough to induce stress by itself, the weekly or monthly reconciling of irregular income (at any scale) versus the inflation that determines all costs of urban living – these are but a few of the many aspects under which a household or an individual can be ‘poor’. Income and food calorie poverty – which have been the measures to judge a household’s position in relation to a line of minimum adequacy – are but two of many interlinked aspects that govern a standard of living which every government promises to raise.

This catechism was repeated when the Sixteenth Lok Sabha began its work, and President Pranab Mukherjee mentioned in his address to the body a common habitat minimum for the 75th year of Indian Independence, which will come in 2022 (at a time when the many vacuous ‘2020 vision documents’ produced during the last decade by every ministry will have neither currency nor remit). Housing for all, Mukherjee assured the Lok Sabha, delivered through the agency of city-building – “100 cities focused on specialised domains and equipped with world-class amenities”; and “every family will have a pucca house with water connection, toilet facilities, 24×7 electricity supply and access”.

That is why, although concerned academicians and veteran NGO karyakartas will exchange prickly criticisms concerning the use in urban study of NSSO first stage units or the use of Census of India enumeration blocks, it is self-determination in the urban context that matters to a degree somewhat greater than the means we choose to use to describe that context. From the time of the ‘approach’ discussions to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07) – which is when the notion, till that time regarded as experimental, that the government can step away without guilt from its old role of providing for the poor in favour of the private sector – the dogma of growth of GDP has included rapid urbanisation.

That is why, although concerned academicians and veteran NGO karyakartas will exchange prickly criticisms concerning the use in urban study of NSSO first stage units or the use of Census of India enumeration blocks, it is self-determination in the urban context that matters to a degree somewhat greater than the means we choose to use to describe that context. From the time of the ‘approach’ discussions to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07) – which is when the notion, till that time regarded as experimental, that the government can step away without guilt from its old role of providing for the poor in favour of the private sector – the dogma of growth of GDP has included rapid urbanisation.

That such GDP growth – setting aside the crippling ecological and social costs which our administrative technorati, for all their ‘progressive’ credentials, do not bring themselves to publicly recognise – is deeply polarising and is especially so in cities is not a matter discussed in any of the 948 city development plans (1,515 infrastructure and housing projects) of the JNNURM. From then on, the seeking and finding of distinctions as they exist within the residential wards of towns and cities has been treated as heretical.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ‘empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

The industry of urban empowerment

The latest issue of the occasional journal Agenda (published by the Centre for Communication and Development Studies) has focused on the subject of urban poverty. A collection of articles brings out the connections between population growth, the governance of cities and urban areas, the sub-populations of the ‘poor’ and how they are identified, the responses of the state to urbanisation and urban residents (links at the end of this post).

My contribution to this issue is titled ‘The industry of ’empowerment’ in which I have described how the urbanisation of India project is being executed in the name of the ‘urban poor’. But the urban poor themselves are lost in the debate over methodologies to identify and classify them and the thicket of entitlements, provisions and agencies to facilitate their ‘inclusion’ and ’empowerment’. I have divided my essay into four parts; here is part one:

2015 will be the tenth year of India’s largest urban recalibration programme. That decadal anniversary will, for one section of our society, be used as proof that new infrastructure in cities has lowered poverty, that new housing has raised the standard of living for those who need it most, that urban rebuilding capital is focused better through such measures and, because of these and like reasons, that giant programmes such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) must continue. With or without the name of India’s first prime minister applied to the mission (itself a noun used liberally to impel urgency into a programme), it will continue, enriched with finance and technology.

2015 will be the tenth year of India’s largest urban recalibration programme. That decadal anniversary will, for one section of our society, be used as proof that new infrastructure in cities has lowered poverty, that new housing has raised the standard of living for those who need it most, that urban rebuilding capital is focused better through such measures and, because of these and like reasons, that giant programmes such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) must continue. With or without the name of India’s first prime minister applied to the mission (itself a noun used liberally to impel urgency into a programme), it will continue, enriched with finance and technology.

The JNNURM, a year from now, will be the foremost symbol amongst several that signal to some 415 million Indians (city-dwellers all, for that will be the approximate urban population a year from now) why city life and city lights are what matter.

For another section of society, less inclined because of experience with administrations indifferent or venal, life in India’s (and Bharat’s) 7,935 towns goes on minus the pithy optimism of governments and their supporters in industry and finance. The promise of higher monthly household incomes is somehow expected to compensate for the grinding travails that urban life in India brings, and it is a promise documented inside 50 years of gazettes and government orders, countless circulars and memoranda, hundreds of reports by committees high-powered and technical.

Still the number of villages that are transformed, statistically and temporally into towns (census and statutory) grows from one census to another (and in between), and still the urban agglomerations — some sprawling uncaring from one district into another, consuming agricultural land and watershed — expand, for the instruction of the market is that it is this process of gathering citizens that leads to the growth of gross domestic product (GDP), the prime mechanic in the alleviation of poverty, whose workings in cities are much studied but elude definition.

The density of programmes and schemes that envelop urban-dwellers — those whose households hover above or below a poverty line, those whose informal wage earnings are insufficient to maintain a crumbling housing board tenement — is confusing, inside administrations as much as outside them. The thicket of entitlements and provisions that have been designed, so we are told, to ensure the provision of ‘services’ and ‘amenities’, confounds navigation.

The density of programmes and schemes that envelop urban-dwellers — those whose households hover above or below a poverty line, those whose informal wage earnings are insufficient to maintain a crumbling housing board tenement — is confusing, inside administrations as much as outside them. The thicket of entitlements and provisions that have been designed, so we are told, to ensure the provision of ‘services’ and ‘amenities’, confounds navigation.

There are economically weaker sections and lower income groups to plan for (provided they remain weaker and lower); there are ‘integrated, reform-driven, fast-track’ sub-missions and components that are aimed at increasing the effectiveness and accountability of urban local bodies, all as part of the ‘Urban Infrastructure and Governance’ standards to be applied under the Urban Infrastructure Development Schemes for Small and Medium Towns (UIDSSMT, which defies any attempt to make acronyms pronounceable) in 65 mission cities.

Prominent within this grand and swelling orchestra of urbanisation are some of the star creations of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty-Alleviation. There is the Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP) and the Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP) and these round up the gamut of concepts proffered by the urban planning dogma of our times: “integrated development of slums through projects”, “providing for shelter, basic services and other related civic amenities with a view towards providing utilities to the urban poor”, “key pro-poor reforms that include the implementation of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act”, and “delivery through convergence of other already existing universal services”.

There are public-private partnership templates to guide business (and the odd social entrepreneurship) through this new topology; there are special purpose vehicles formed that mendaciously grey the distinctions between bond and financial markets and the greater public good, but which we are assured will function as the money backstop for public administrations whose clerks peer befuddled at slick online reporting formats (transparency at work, round the clock, accessible through apps on the beneficiaries’ tablet phones).

There is ‘inclusion’ — that most essential salt that flavours the substance of governance today — to be found in every direction. There are plenty of beneficiaries to enlist in this urban social re-engineering that is proceeding on a scale and pace unthinkable a generation ago in our towns (public sector housing colonies and waiting lists for scooters), when ‘income inequality’ was an uncommon topic of discussion and ‘gini coefficient’ had yet to become a society’s alarm bell. The new cadre of GDP engineers is well schooled in the language of human rights and normative justice, and so we have ‘Social Mobilisation and Institution Development’ which attends ‘Employment through Skills Training and Placement’, both of which facilitate ’empowerment, financial self-reliance, and participation and access to government’.

There is ‘inclusion’ — that most essential salt that flavours the substance of governance today — to be found in every direction. There are plenty of beneficiaries to enlist in this urban social re-engineering that is proceeding on a scale and pace unthinkable a generation ago in our towns (public sector housing colonies and waiting lists for scooters), when ‘income inequality’ was an uncommon topic of discussion and ‘gini coefficient’ had yet to become a society’s alarm bell. The new cadre of GDP engineers is well schooled in the language of human rights and normative justice, and so we have ‘Social Mobilisation and Institution Development’ which attends ‘Employment through Skills Training and Placement’, both of which facilitate ’empowerment, financial self-reliance, and participation and access to government’.

About 30 years ago, The State of India’s Environment 1984-85 (Centre for Science and Environment) noted in a tone of cautious optimism that “planners are beginning to realise that squatters are economically valuable citizens who add to the gross national product by constructing their own shelter, no matter how makeshift, which saves the government a considerable amount of money”. That was a time when governments still sought to save money and the CSE report went on to explain that squatters “are upwardly mobile citizens in search of economic opportunity and have demonstrated high levels of enterprise, tenacity, and ability to suffer acute hardships; that the informal sector in which a majority of the slum-dwellers are economically active contributes significantly to the city’s overall economic growth; and that they should be helped and not hindered”.

[Articles in the Agenda issue, Urban Poverty, are: How to make urban governance pro-poor, Counting the urban poor, The industry of ’empowerment’, Data discrepancies, The feminisation of urban poverty, Making the invisible visible, Minorities at the margins, Housing poverty by social groups, Multidimensional poverty in Pune, Undermining Rajiv Awas Yojana, Resettlement projects as poverty traps, Participatory budgeting, Exclusionary cities.]

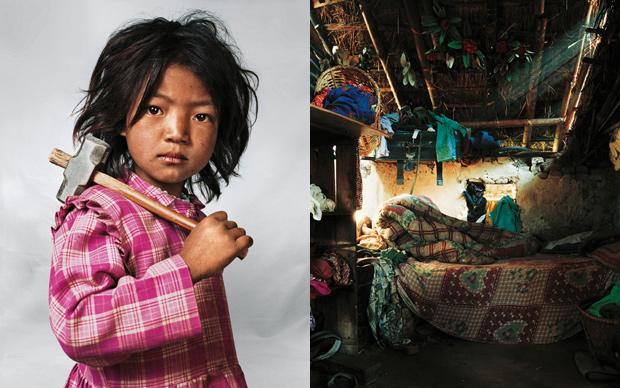

Where the children sleep

These pictures are from James Mollison’s book of photographs of children from around the world and where they sleep (thanks to The Telegraph of Britain for running an article on the book). Mollison hopes his photographs will encourage children to think about inequality. He sees his pictures as “a vehicle to think about poverty and wealth, about the relationship of children to their possessions, and the power of children – or lack of it – to make decisions about their lives”.

Indira, seven, lives with her parents, brother and sister near Kathmandu in Nepal. Her house has only one room, with one bed and one mattress. At bedtime, the children share the mattress on the floor. Indira has worked at the local granite quarry since she was three. The family is very poor so everyone has to work. There are 150 other children working at the quarry. Indira works six hours a day and then helps her mother with household chores. She also attends school, 30 minutes’ walk away. Her favourite food is noodles. She would like to be a dancer when she grows up. Picture: The Telegraph / James Mollison / Chris Boot Ltd

Jasmine, four, lives in a big house in Kentucky, USA, with her parents and three brothers. Her house is in the countryside, surrounded by farmland. Her bedroom is full of crowns and sashes that she has won in beauty pageants. She has entered more than 100 competitions. Her spare time is taken up with rehearsal. She practices her stage routines every day with a trainer. Jazzy would like to be a rock star when she grows up. Picture: The Telegraph / James Mollison / Chris Boot Ltd

Home for this boy and his family is a mattress in a field on the outskirts of Rome, Italy. The family came from Romania by bus, after begging for money to pay for their tickets. When they arrived in Rome, they camped on private land, but the police threw them off. They have no identity papers, so cannot obtain legal work. The boy’s parents clean car windscreens at traffic lights. No one from his family has ever been to school. Picture: The Telegraph / James Mollison / Chris Boot Ltd

Kaya, four, lives with her parents in a small apartment in Tokyo, Japan. Her bedroom is lined from floor to ceiling with clothes and dolls. Kaya’s mother makes all her dresses – Kaya has 30 dresses and coats, 30 pairs of shoes and numerous wigs. When she goes to school, she has to wear a school uniform. Her favourite foods are meat, potatoes, strawberries and peaches. She wants to be a cartoonist when she grows up. Picture: The Telegraph / James Mollison / Chris Boot Ltd

Lamine, 12, lives in Senegal. He is a pupil at the village Koranic school, where no girls are allowed. He shares a room with several other boys. The beds are basic, some supported by bricks for legs. At six every morning the boys begin work on the school farm, where they learn how to dig, harvest maize and plough the fields using donkeys. In the afternoon they study the Koran. In his free time Lamine likes to play football with his friends. Picture: The Telegraph / James Mollison / Chris Boot Ltd

Extracted from ‘Where Children Sleep’ by James Mollison (Chris Boot).

India’s 681 million hungry rural citizens

What do and what can rural residents spend on food and the essentials of living in India? This chart gives us an indication. It is based on new data contained in the latest revelation (my word, not theirs) from the National Sample Survey Office and is titled ‘Key Indicators of Household Consumer Expenditure in India’ (the 68th Round of sampling, for those who follow the extraordinary programme of this sterling statistical organisation).

What do and what can rural residents spend on food and the essentials of living in India? This chart gives us an indication. It is based on new data contained in the latest revelation (my word, not theirs) from the National Sample Survey Office and is titled ‘Key Indicators of Household Consumer Expenditure in India’ (the 68th Round of sampling, for those who follow the extraordinary programme of this sterling statistical organisation).

There is data enough in the volume to inform us, clearly and starkly, that the cumulative impact of several years of food price inflation is hurting households more with every passing quarter. Consider what this new data release tells us:

* That the average rural monthly expenditure per person was lowest in the states of Odisha and Jharkhand (around Rs 1,000) and also in Chhattisgarh (Rs 1,027).

* That the average rural monthly expenditure per person was lowest in the states of Odisha and Jharkhand (around Rs 1,000) and also in Chhattisgarh (Rs 1,027).

* In Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, the rural monthly expenditure per person was about Rs 1,125 to Rs 1,160.

* In urban India (not shown in this chart, but I will add to this posting with an expanded update) Bihar had the lowest monthly expenditure per person (called monthly per capita expenditure by the NSSO and abbreviated to MPCE) of Rs 1,507.

* In Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, urban MPCE was between Rs 1,865 and Rs 2,060. These six were the six major states with the lowest MPCEs for both rural and urban citizens.

But those are averages, and in this data release, the NSSO has divided its usual ten deciles even further for the lowest and highest deciles. (The decile is the surveyed population divided into tenths, with these being classified by expenditure level.) Doing so gives us a better view of the elastic expense trends in the top ten per cent of the population, the class which is so pampered by the central government. For rural India then, the 5th percentile of the MPCE distribution was estimated as Rs 616 and the 10th percentile as Rs 710 – and these are all-India averages.

[The spreadsheet with the table and chart is here. You can find the highlights of the NSSO study here.]

About half the total rural population is thus estimated to have a MPCE below Rs 1,198. Only about 10% of the rural population reported household MPCE above Rs 2,296 and only 5% reported MPCE above Rs 2,886 (this is using what is called the ‘modified mixed reference period’ or MMRP, in which the person interviewed is asked to recall purchases made over two different lengths of time, for different sorts of goods). The bottom-line is that food accounted for about 53% of the value of the average rural Indian’s household consumption during 2011-12.

About half the total rural population is thus estimated to have a MPCE below Rs 1,198. Only about 10% of the rural population reported household MPCE above Rs 2,296 and only 5% reported MPCE above Rs 2,886 (this is using what is called the ‘modified mixed reference period’ or MMRP, in which the person interviewed is asked to recall purchases made over two different lengths of time, for different sorts of goods). The bottom-line is that food accounted for about 53% of the value of the average rural Indian’s household consumption during 2011-12.

This included 11% for cereals and cereal substitutes, 8% for milk and milk products, another 8% on beverages and processed food, and 6.5% on vegetables. Among non-food item categories, fuel for cooking and lighting accounted for about 8%, clothing and footwear for 7%, medical expenses for about 6.5%, education for 3.5%, conveyance for 4%, other consumer services for 4%, and consumer durables for 4.5%.

This ought to be a ringing alarm about access to food for the country’s planners, who are otherwise obsessed with GDP growth and whether India is cosmetically dolled up enough to attract global finance capital. It hasn’t sounded even a muted gong, and even if it had, one stunning inference from this table has been ignored – that this is an indicator of food and multi-dimensional poverty and that millions of rural residents are unable to afford food and basic services.

How so? Look at the chart again. Imagine, at just above the line marking 2,000 rupees, a dotted red line at a level of around 2,070 rupees. That is the equivalent (before the recent fall in the rupee’s value against the US dollar) of USD 1.25 a day, which has (ill-advisedly) been cemented in development wisdom as a poverty line that can be applied in countries like India. Let’s accept that in order to focus on what the new NSSO data tells us.

At the Rs 2,070 level we see that for a relatively prosperous state like Haryana (a former Green Revolution state) about 50% of the rural population cannot spend, per person per month, this amount. The percentage of the rural population below and above this line is similar, more or less, for Punjab (also a former Green Revolution state) and for Kerala (which is not, but has income from economic migrants abroad).

At the Rs 2,070 level we see that for a relatively prosperous state like Haryana (a former Green Revolution state) about 50% of the rural population cannot spend, per person per month, this amount. The percentage of the rural population below and above this line is similar, more or less, for Punjab (also a former Green Revolution state) and for Kerala (which is not, but has income from economic migrants abroad).

But the entire rural populations of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha cannot spend this amount, because they do not earn it. How many is that? Using the 2001-2011 population growth rates (for rural populations of states) this means 98.96 million in rural Bihar, 20.65 million in rural Chhattisgarh, 26.52 million in rural Jharkhand and 36.19 million in rural Odisha are below this line. What of other states with large rural populations?

In Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, 90% of the rural population is below this line and that means 25.23 million in Assam, 49.90 million in Madhya Pradesh, 147.25 million in Uttar Pradesh, and 57.26 million in West Bengal. In Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, 80% of the rural population is below this line and that means 28.52 million in Gujarat, 30.66 million in Karnataka, 50.77 million in Maharashtra and 43.55 million in Rajasthan. In Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, 70% of the rural population is below this line and that means 39.64 million in Andhra Pradesh and 26.56 million in Tamil Nadu.

Taken together those rural populations are 681.72 million (more than twice the population of the USA). They are 78% of India’s 2013 rural population, almost eight out of ten rural citizens.