Posts Tagged ‘Chhattisgarh’

Three months of swinging Celsius

The middle of February is when the chill begins to abate. The middle of May is when the monsoon is longed for. In our towns, district headquarters and cities, that climatic journey of 90 days is one of a steady rise in the reading of the temperature gauge, from the low 20s to the mid 30s.

This large panel of 90 days of daily average temperatures shows, in 57 ways, the effects of the rains that almost every district has experienced during the last two months. For each city, the curved line is the long period ‘normal’ for these 90 days, based on daily averages. Also for each city, the second line which swings above and below the ‘normal’ is the one that describes the changes in its daily average from February to May 2015.

[You can download (1.52MB) a full resolution image of the panel here.]

Where this second line crosses to rise above the normal, the intervening space is red, where it dips below is coloured blue. The patches of red or blue are what tell us about the effects of a lingering winter, or rains that have been called ‘unseasonal’ but which we think signal a shift in the monsoon patterns.

The 90-day temperature chart for Goa, with daily averages nearer the long period normal over the latter half.

Amongst the readings there is to be found some general similarities and also some individual peculiarities. Overall, there are more blue patches than there are red ones, and that describes how most of the cities in this panel have escaped (till this point) the typical heat of April and May. The second noteworthy general finding is that these blue patches occur more frequently in the second half of the 90 days, and so are the result of the rainy spells experienced from March to early May.

Hisar (in Haryana) has remained under the normal temperature line for many more days than above or near it. So have Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh), Pendra (Chhattisgarh), Ranchi (Jharkhand), Nagpur (Maharashtra) and Jharsuguda (Odisha).

On the other hand in peninsular and south India, the below ‘normal’ daily average temperature readings are to be found in the latter half of the time period, coinciding with the frequent wet spells. This we can see in Kakinada, Kurnool and Anantapur (Andhra Pradesh), Bangalore, Gadag and Mangalore (Karnataka), Chennai, Cuddalore and Tiruchirapalli (Tamil Nadu) and Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala). [A zip file with the charts for all 57 cities is available here (1.2MB).]

What pattern will the next 30 days worth of temperature readings follow? In four weeks we will update this bird’s eye view of city temperatures, by which time monsoon 2015 should continue to give us more blues than reds. [Temperature time series plots are courtesy the NOAA Center for Weather and Climate Prediction.]

The cities and their multitudes

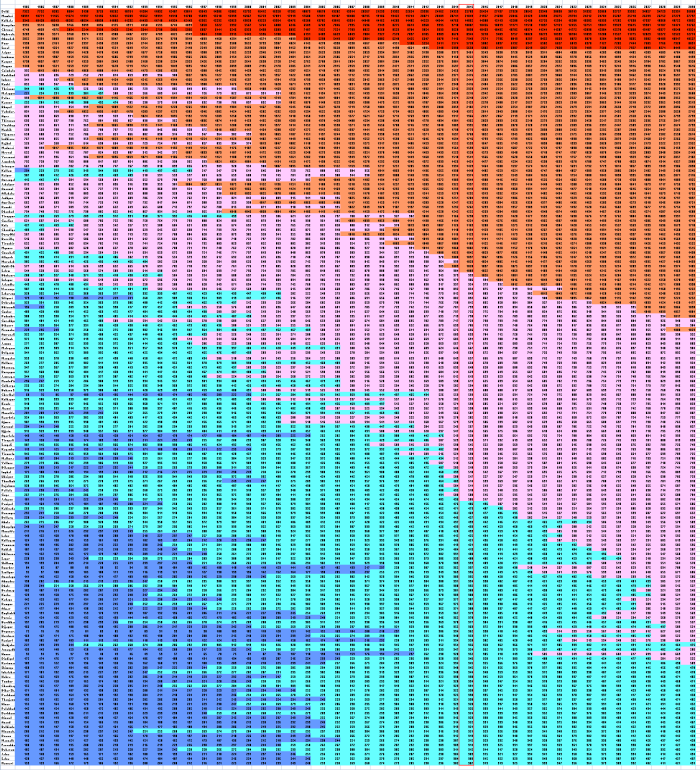

The 166 Indian cities in the UN population list. What do the colours mean? Dark blue is for city populations up to 250,000; light blue is 250,000-500,000; pink is 500,000 to 1 million; orange is 1 million to 5 million; red is 5 million and above. The source for the data is ‘World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision’, from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Bigger cities growing at a rate faster in the last decade than earlier decades. This is what the image shows us. These are 166 cities of India whose populations in 2014 were 300,000 and above. The jagged swatches of colour that seem to march diagonally across the image describe tiers of population, for the table is arranged according to the populations of these cities in 2015, with the annual series beginning in 1985 and extending (as a forecast) until 2030.

The populations of four cities will cross 0.5 million in 2015: Jalgaon (Maharashtra, whose population will be 506,000 in 2015), Patiala (Punjab, 510,000), Thoothukudi (Tamil Nadu, 514,000) and Imphal (Manipur, 518,000). They will join a group of cities which in 2014 crossed the 0.5 million mark: Gaya (Bihar, 508,000 in 2015), Rajahmundry (Andhra Pradesh, 511,000), Udaipur (Rajasthan, 517,000), Bilaspur (Chhattisgarh, 518,000), Kayamkulam (Kerala, 533,000) and Agartala (Tripura, 550,000).

Just ahead of these are Vellore (Tamil Nadu, whose population in 2015 will be 528,000 and which crossed 0.5 million in 2013), Mathura (Uttar Pradesh, 529,000 and 2014), Tirunelveli (Tamil Nadu, 530,000 and 2011), Sangli (Maharashtra, 545,000 and 2009), Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh, 550,000 and 2013), Ujjain (Madhya Pradesh, 556,000 and 2009), Kurnool (Andhra Pradesh, 567,000 and 2012), Muzaffarnagar (Uttar Pradesh, 587,000 and 2011), Erode (Tamil Nadu, 590,000 and 2010) and Cherthala (Kerala, 593,000 and 2013).

To make this chart I have used the data from ‘World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision’, from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. The 166 cities of India are extracted from the main table, ‘Annual Population of Urban Agglomerations with 300,000 Inhabitants or More in 2014, by Country, 1950-2030’.

The top 20 oryza districts of India

Some of the rice varieties of Kerala state, displayed during the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) meeting (COP 11) in Hyderabad in 2012 October.

Which are the districts of India which grow the most rice? Let’s look at the country-level numbers for rice in 2007-08, in 2008-09 and in 2009-10. In 2007-08 the total tonnage reported by the rice growing districts was 90.071 million tons, grown in 553 districts that reported rice harvests, and which grew their rice over 41.306 million hectares (413,000 sq kilometres, a combined area bigger than Paraguay).

In 2008-09 the total tonnage reported by the rice growing districts was 93.148 mt, grown in 508 districts that reported rice harvests, and which grew their rice over 42.759 m ha (427,590 sq km, which is a combined area nearly as large as Iraq). In 2009-10 the total tonnage reported by the rice growing districts was 80.07 mt, grown in 408 districts that reported rice harvests, and which grew their rice over 34.978 m ha (349,780 sq km which is a combined area larger than the Republic of the Congo). [See also this earlier entry on rice-growing districts of India.]

So, looking at the rice totals, there were ups and downs even over three seasons – remember that the monsoon of 2009 was poor and we had drought conditions in many districts. I would have liked to include the data for 2010-11 at district level, but this is still minus West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh and I can’t understand why this is so because the regular ‘advance estimates’ released by the Ministry of Agriculture are supposed to be based on what the states send in as crop growing data every quarter. The three years before 2007-08 should help us understand these trends better and as soon as I collect and clean up data for those years I will add to this post. Meanwhile, you can download the spreadsheet of the top 20 districts for these three years here (xlsx).

Which are the districts that produce the most rice in India, year after year? Based on this three-season set, here’s what we have. In Andhra Pradesh the districts are East Godavari, Guntur, Karimnagar, Krishna, Nalgonda, Nellore and West Godavari. In Chhattisgarh it is Raipur. In Punjab the districts are Firozpur, Ludhiana, Moga, Patiala and Sangrur. In West Bengal the districts are 24 Parganas (South), Bankura, Birbhum, Burdwan, Hooghly, Midnapur (East), Midnapur (West) and Murshidabad.

The top rice-growing districts, 2007-08 to 2009-10, in West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab and Chhattisgarh.

How much do these top 20 (there are 21 top districts over these three years) by year contribute to the country’s total rice harvest? In 2007-08 they contributed 23.16 mt which was 25.7% of the total rice harvest; in 2008-09 they contributed 24 mt which was again 25.7% of the total; in 2009-10 they contributed 21.93 mt which was 27.3% of the total.

Using a tonnage-based ranking, we have seen how the top 20 rice-growing districts contribute around a quarter of India’s total rice harvest. How different are the top 20 from a group of 20 rice-growing districts further down in the tonnage ranking, for example the 20 districts between 40 and 59 for those years? And is the 40-59 group of districts more diverse (geographically) and have more growing variety (what else do they grow?) than is shown by the dominance of the same districts from West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab in the top 20?

Let’s see what the numbers say. In 2007-08 the 20 districts between ranks 40 and 59 (ranked by tonnage) together harvested 7.20 mt, in 2008-09 it was 7.17 mt and in 2009-10 it was 6.90 mt.

Hence in all three years this set of 20 contributed around a third less rice than the top 20. This is a difference which helps explain the big gap between the tonnage for districts even between those at 80th and 90th percentiles – see the quick comparison chart for how concentrated India’s rice production is in relatively few rice-growing districts.

This cursory look at three years’ data for rice and the districts it is grown in raise several questions. Most important, why do we have complete data (at district level) only until 2009-10 and not after? I find this puzzling since we have advance estimates (released by the Ministry of Agriculture four times a year) for major cereals, pulses and commercial crops even into 2012-13. On what data from the states are these advance estimates then based if we can’t see district figures?

Also, why is there still so much concentration of rice production – 25% to 27% of the total – in only 20 districts? Depending on how many districts report rice harvests in a year, these 20 comprise no more than 4% or 5% of the total rice-growing districts in India. The National Food Security Mission (which concentrates on rice, wheat and pulses) is active in 137 districts specifically for growing rice, so in what way is this concentration of production significant? More on this matter to follow.

Quiet numbers tell district tales – rural and urban India, part 6

In north-east Mumbai (Bombay), open land under high-tension cables becomes a place for many cricket games on a Sunday afternoon.

Census 2011 also informs both the incumbent ‘sirkar’ and us that there are 22 districts in which literacy rates for the rural female population are above 74% (all 14 of Kerala’s districts are included). However, it is in the next 10% range of literacy rates – 74% to 64% – that gains since the 2001 census must be protected and this set includes 82 districts. It is a widely dispersed set, comprising districts from 21 states and union territories.

There are 11 from Maharashtra (including Sangli, Bhandara and Gondiya), 9 from Punjab (including Kapurthala, Gurdaspur and Sahibzada), 7 from Orissa (including Jagatsinghpur, Kendrapara and Bhadrak), 7 also from Himachal Pradesh (including Una, Kangra and Solan), 6 from Tamil Nadu (including Thoothukkudi and Nagapattinam) and 5 from Gujarat (including Navsari and Mahesana).

In the background, some of the most expensive office space in the world, Mumbai's Nariman Point business district. In the foreground, temporary shanties on the beach.

The Office of the Registrar General of India, which administers the Census, has cautioned that all the data releases so far are still provisional figures. However, the implications are now plain to see, and give rise to a set of socio-economic questions which demographic and field research over the 12th Plan Period (2012-17) will enlarge and expand upon. Is there for example a correlation between districts whose rural populations have unfavourable female to male gender ratios and districts in which female literacy ratios are low? Comparing the bottom 100 districts under both conditions shows that there are only 12 districts in which both conditions are present (5 in Uttar Pradesh, 2 in Rajasthan, and 2 in Jammu & Kashmir).

A valley in the western hills of Maharashtra state in summer, exhibiting denuded hillsides and scant grazing for shepherds. From villages such as this one, youth and families make their way to the cities.

Most encouraging is that there are 40 districts in which the ratio of the number of literate females to literate males (this is a different ratio from literacy rate), is 0.90 or better, ie there are 900 or more literate females to 1,000 literate males. In this set are all Kerala’s 14 districts but also 13 districts from the Northeast (from Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland).

The remainder are from island Union Territories, from the southern states (3 from Karnataka, 2 from Andhra Pradesh and one each from Tamil Nadu and the Union Territory of Puducherry), from hill states (2 from Uttarakhand, 2 from Himachal Pradesh) and one from Maharashtra. It is these districts that provide abundant reason for the allocation of a minimum 6% of GDP allocation for education – a long-standing commitment – which must begin to be fulfilled in the 2012-17 Plan period.

Thane district, north of the Mumbai metropolitan region, has experienced one of the fastest growths in population in India over the last decade.

How will the Government of India consider these early indicators from Census 2011? How will India’s civil society and the great breadth of organisations – voluntary groups, people’s movements, rural foundations and the like – which have been delivering development ‘outcomes’, year after year, without the benefit of budgetary support but motivated by the plain fact that inequity still exists, how will this group see these indicators?

The Government of India revels in presenting contradiction as a substitute for careful, evidence-based and inter-generational planning. When downward trends – such as those seen in female illiteracy and in the gender ratios of the 0-6 age-group – have been slow over the last 25 years, there is a need to set long-term objectives that are not tied to the end of the next available Plan period, but which use a Plan direction to help achieve them. In this, the Approach Paper to the 12th Five-Year Plan has failed quite signally, because its authors have not drawn the only possible conclusions from the Census 2011 data presented till date. Yet others have done so, notably India’s civil society and its more responsive group of academics. Hence the abundance of contradictions in all major documents – the Approach Paper being the most important, annual Economic Surveys being another type – which seek to reassure one section while in fact underwriting the ambitions of another.

Rural labour pitches camp. Mobile populations such as this one move from more disadvantaged districts to less, as even intermittent agricultural wages and harsh living conditions are better than debt.

So we see that a state which must ensure provision of Right to Education to every child up to the age of 14 years, because it is constitutionally bound to do so, complains in the planning phase itself that scarce resources constrain it from carrying out its duties and therefore advises its citizens that measures like public-private partnership (PPP) should be resorted to. How will such cunning better the lives and present culturally relevant opportunities for the rural populations in the remaining 591 districts which are under the 0.90 ratio for literate females to literate males? What will the emphasis on vocational training (for the urban job pools) instead of people’s empowerment mean for the rural populations in 403 districts where this ratio is less than 0.75 – which means the number of literate rural females is under three-fourths the number of literate males – and in 69 of these districts it is even under 0.60 (25 in Rajasthan, 14 in Uttar Pradesh, 9 in Madhya Pradesh, 6 in Jammu and Kashmir)?

[This is the sixth of a small series of postings on rural and urban India, which reproduces material from my analysis of Census 2011 data on India’s rural and urban populations, published by Infochange India. See the first in the series here; see the second in the series here; see the third in the series here; see the fourth in the series here; see the fifth in the series here.]

Quiet numbers tell district tales – rural and urban India, part 5

Teenager on a bicycle in rural Maharashtra, western India. At the current rate of migration from rural districts to urban centres, this youth may not stay in the farm labour pool for much longer.

What effect has this imbalanced ratio, so common in the rural populations of districts, on literacy and education? Census 2011 has told us so far that there are 55 districts in which the rural literacy rate is 74% or higher — this is the national effective literacy rate (for the population that is seven years old and above) which is a figure derived from rural and urban, male and female literacy rates. The literacy rates in these 55 districts are for all persons, female and male together. They range from 74% to 89%. All 14 of Kerala’s districts are among the 55, there are 7 districts from Maharashtra, 5 from Tamil Nadu, and 4 each from Mizoram, Orissa and Himachal Pradesh.

A lorry driver poses with his cargo, new tractors. The depletion of agricultural labour has turned agricultural machinery a fast-growing industrial sector. Worryingly for India, government planners see capital used for machinery and industrial agriculture as evidence of 'growth'. But food security remains uncertain for many rural communities.

The top 10 districts in this set are all from Kerala save one, East Delhi. But these 55 districts have returned literacy rates that will form the basis of study and analysis in the years to come, they are outnumbered, by a factor of more than 11 to 1, by districts whose rural populations lie under the 74% national mark, and this too will serve as an early indicator, continually updated, of the commitment of the Indian state to its implementation of the Right to Education (RTE) Act of 2009, and of the results of the first 10 years of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan.

Since its inception in 2001-02 the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) has been treated by the Government of India and the states as the main vehicle for providing elementary education to all children in the 6-14 age-group. Its outcome — this is how the annual and Plan period results of India’s ‘flagship’ national programmes are now described — is the universalisation of elementary education. The Right to Education Act (RTE) of 2009 gives all children the fundamental right to demand eight years of quality elementary education. For the planners in the Ministry of Human Resource Development, the effective enforcement of this right requires what they like to call ‘alignment’ with the vision, strategies and norms of the SSA. In so doing, they immediately run into a thicket of problems for, to begin with, there are half-a-million vacancies of teachers in the country, another half-million teachers are required to meet the RTE norms on pupil-teacher ratios, and moreover 0.6 million teachers in the public school system are untrained.

This is the creaking administrative set-up against which the total literacy rates of the 585 districts whose rural populations are under the 74% mark must be viewed. Of these, 209 districts have literacy rates for their rural populations which are between 50% and 60%. This set of districts includes 33 from Uttar Pradesh, 30 from Madhya Pradesh, 20 from Bihar, 18 from Jharkhand, 17 from Rajasthan, 13 each from Assam and Andhra Pradesh, and 9 from Karnataka. And finally, there are 95 districts whose literacy rates of the rural population are under 50%.

Low-cost housing in north Mumbai (Bombay). Colonies such as this are typical: unclean surroundings caused by an absence of civic services, minimal water and sanitation for residents, no route to remedy because of political and social barriers.

This set of districts at the bottom of the table includes 17 from Bihar, 14 from Rajasthan, 9 each from Uttar Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir, 7 from Madhya Pradesh and 6 each from Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Arunachal Pradesh. The districts of Yadgir (Karnataka), Purnia (Bihar), Shrawasti (Uttar Pradesh), Pakur (Jharkhand), Malkangiri, Rayagada, Nabarangapur, Koraput (all Orissa), Tirap (Arunchal Pradesh), Barwani, Jhabua, Alirajpur (all Madhya Pradesh), and Narayanpur, Bijapur and Dakshin Bastar Dantewada (all Chhattisgarh) are the 15 districts at the very base of the table with literacy rates of the rural population at under 40%.

Over 11 Plan periods there have been some cumulative gains in a few sectors. Today, in rural areas, seven major flagship programmes are being administered, with less overall coordination between them than is looked for – a contrast against the ease with which the central government’s major ministries collaborate on advancing the cause of the urban elite — but which nonetheless have given us evidence that their combined impact has improved the conditions of some.

A man transports an LPG cylinder, to be used as cooking fuel, to his home in a shanty colony in north Mumbai (Bombay). Already burdened by the high cost of petroleum products, slum-dwellers are forced to pay a premium for cooking fuels and water.

The seven programmes are: the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), Indira Awas Yojana (IAY), the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) and Total Sanitation Campaign (TSP), the Integrated Watershed Development Programme (IWDP), Pradhan Mantri Grameen Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), and rural electrification which includes separation of agricultural feeders and includes also the Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana (RGGVY).

For the local administrator these present a bewildering array of reporting obligations. A hundred years ago, such an administrator’s lot was aptly described by J Chartres Molony, Superintendent of Census 1911 in (the then) Madras: “The Village Officer, source of all Indian information, is the recorder of his village, and it well may be that amid the toils of keeping accounts and collecting ‘mamuls’, he pays scant heed to what he and his friends consider the idle curiosity of an eccentric sirkar.”

[This is the fifth of a small series of postings on rural and urban India, which reproduces material from my analysis of Census 2011 data on India’s rural and urban populations, published by Infochange India. See the first in the series here; see the second in the series here; see the third in the series here; see the fourth in the series here.]

Quiet numbers tell district tales – rural and urban India, part 4

Dense colonies of low-rise apartment blocks in north-eastern Mumbai (Bombay). These date from the 1980s and despite their disrepair are out of reach for some 60% of the giant city's population which live in 'upgraded' slums.

Dr C Chandramouli, Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, presaged the insights that would be provided by new census data in his introduction to the first provisional paper on the 2011 Census: “It provides valuable information for planning and formulation of policies by the government and is also used widely by national and international agencies, scholars, business persons, industrialists, and many more. In addition, the Census provides a basic frame for conduct of other surveys in the country. Any informed decisionmaking that is based on empirical data is dependent on the Census.”

When taken together with the 355 districts whose rural populations are all a million and above, the implications of such a concentration of the 0-6-year-old population in talukas and tehsils (more than those in town wards) become manifold. An immediate rendering of this concentration will take place in the health sector for it is there that imbalances in public expenditure and budget have been most severe.

The change in literacy rates for India's states from 2001 to 2011, with the 0-6 year olds excluded. The colours are: red (75% and below), ochre (75-80%), yellow (80-85%), lime green (85-90%) and green (90% and above). Maps: Census of India 2011

The Government of India has time and again claimed that the 11th Five-Year Plan (2007-12) has sought to raise the share of public expenditure on health (both central and in the states) from less than 1% of GDP in 2006-07 to 2% and then 3%. For this, the National Rural Health Mission (launched in 2005) was intended to strengthen healthcare infrastructure in rural areas, provide more sub-centres, better staff and equip primary health and community health centres.

Census 2011 will, over the months to come, indicate the degree to which these lofty aims — often held up as evidence of the government’s commitment to social equity — have been met. To do this, the ratios will be layered between study outputs that bring out the insights of correlating large demographic data sets — district health services, the national family health survey, planned rounds of the National Sample Survey and, despite the defensible criticism levelled against it, the 2011 BPL survey. Within this dauntingly complex data framework will need to be placed the Plan targets relating to infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, total fertility rate, under-nutrition among children, anaemia among women and girls, provision of clean drinking water for all, and raising child gender ratio for the age-group of 0-6.

Where do the 640 districts and their rural populations lie on a simple child gender ratio scale? Ranked by female to male ratio within the 0-6 years category of population, the top 10% of all districts (that is, 64 districts) register a gender ratio of at least 0.97 and up to 1.01. The districts with the 20 most favourable female to male ratios for the 0-6 population are Dakshin Bastar Dantewada, Bastar, Bijapur, Koriya, Rajnandgaon, Narayanpur and Korba (all Chhattisgarh); Tawang, Papum Pare and East Siang (all Arunachal Pradesh); Nabarangapur and Malkangiri (Orissa); Lahaul and Spiti (Himachal Pradesh), Nawada (Bihar), Chandauli (Uttar Pradesh), Mamit (Mizoram), Pashchimi Singhbhum (Jharkhand), Tinsukia (Assam), South Andaman, and West Garo Hills (Meghalaya).

Vegetables being farmed on agricultural land between two city wards of Panaji (Goa). As the populations of smaller towns in India has risen, their footprint on cultivable land has grown.

Among the top 10% of districts with gender ratios for the 0-6 age group that are favourable to females, Chhattisgarh has 14 while Orissa, Meghalaya, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh have 6 each. These are considered, by their states and by the central government’s ministries and departments, to be ‘backward’ districts, tribal in character, lacking in infrastructure and below par in economic development (discounting for this index the proclivity of the state to steal natural resources in the commons, the better to convert it to GDP with). Yet the residents of these districts have proven, as the 2011 data so emphatically shows, that they practice an equality that is far closer to that enunciated in our Constitution than is to be found in the ranks of the million-plus cities.

Even so, the picture at the other end of the scale is a worrisome one. Within the 0-6 years category of the rural population of districts, there are 154 districts whose female to male ratio is less than 0.90, ie 9 girls or less for every 10 boys. In this large set of districts with unfavourable gender ratios amongst the rural population category of 0-6 years, the range of this ratio drops to 0.70 (the average gender ratio for this group of districts being 850 girls to 1,000 boys). There are 24 districts in UP in this set (out of the state’s 71 districts), 20 districts each in Punjab and Haryana (out of their totals of 20 and 21 respectively), 18 each in Rajasthan and Maharashtra (out of 33 and 35 respectively) and 14 in Jammu & Kashmir (out of 22).

[This is the fourth of a small series of postings on rural and urban India, which reproduces material from my analysis of Census 2011 data on India’s rural and urban populations, published by Infochange India. See the first in the series here; see the second in the series here; see the third in the series here.]

The Census of India has released the first batch of the primary census abstract. This is the heart of the gigantic matrix of numbers that describes India’s population (to be correct technically, India’s population as it was in 2011 March). The PCA, as it is fondly known amongst the tribe that speak its arcane language, is the final and corrected set of numbers of the populations of India’s states, districts, blocks and villages – this corrects, if such correction was required, the data used in the Census 2011 releases between 2011 and now, which were officially called provisional results.

The Census of India has released the first batch of the primary census abstract. This is the heart of the gigantic matrix of numbers that describes India’s population (to be correct technically, India’s population as it was in 2011 March). The PCA, as it is fondly known amongst the tribe that speak its arcane language, is the final and corrected set of numbers of the populations of India’s states, districts, blocks and villages – this corrects, if such correction was required, the data used in the Census 2011 releases between 2011 and now, which were officially called provisional results.