Posts Tagged ‘kisan’

Seeds and knowledge: how the draft seeds bill degrades both

[ This comment is published by Indiafacts. ]

The central government has circulated the Draft Seeds Bill 2019, the text of which raises several red flags about the future of kisan rights, state responsibilities, the role of the private sector seed industry, and genetic engineering technologies.

The purpose of the 2019 draft bill is “to provide for regulating the quality of seeds for sale, import and export and to facilitate production and supply of seeds of quality and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”. The keywords in this short statement of the draft bill’s objectives are: regulate, quality, sale, import, export.

This draft follows several earlier legislations and draft legislations in defining and treating seed as a scientific and legal object, while ignoring entirely the cultural, social, ritual and ecological aspect of seed. These earlier legal framings included the 2004 version of the same draft bill, the Protection of Plant Variety and Farmers Right Act of 2001, the 1998 Seed Policy Review Group and its recommendations (New Policy on Seed Development), the Consumer Protection Act of 1986, the National Seeds Project which began in 1967 (under assistance/direction of the World Bank), the Seeds Act of 1966 (notified in 1968, fully implemented in 1969), and the establishing of the National Seeds Corporation under the Ministry of Agriculture in 1961.

With 53 clauses spread over 10 chapters, the draft bill sees seed as being governed by a central and state committees (chapter 2), requiring registration (including a national register, chapter 3), being subject to regulation and certification (chapter 4), with other chapters on seed analysis and testing, import and export and the powers of central government. (The draft bill is available here, 68mb file.)

In such a conception of seed and the various kinds of activities that surround the idea of seed today, the draft bill reproduces a pattern that (a) has remained largely unchanged for about 60 years, and (b) is far more faithful to an ‘international’ (or western) legal interpretation of seed than it is to the Indic recognition of ‘anna‘ (and the responsibilities it entails including the non-ownership of seed).

The 2019 draft bill is attempting to address three subjects that should be dealt with separately. These are: farmers’ rights, regulation and certification, property and knowledge. Each of these exists as a subject closely connected with cultivation (krishi as expressed through the application of numerous forms of traditional knowledge) and the provision of food crops, vegetables and fruit. But that they exist today as semantic definitions in India is only because of the wholesale adoption of the industrially oriented food system prevalent in the western world (Europe, north America, OECD zone).

‘Farmers’ rights’ became a catchphrase of the environmental movement that began in the western world in the 1960s and was enunciated as a response to the chemicalisation of agriculture. When the phrase took on a legal cast, it also came to include the non-ownership and unrestricted exchange of seeds, as a means to demand its distinguishing from the corporate ownership of laboratory derived seed. But farmers’, or kisans‘, rights in India? As a result of what sort of change and as a result of what sort of hostile encirclement of what our kisans have known and practised since rice began to be cultivated in the Gangetic alluvium some eight millennia ago?

Regulation and certification (which includes the opening of a new ‘national register’ of seeds) is fundamentally an instrument of exclusion. It stems directly from the standpoint of India’s national agricultural research system, which is embodied in the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), and which is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Department of Biotechnology, and is designed to shrink the boundaries of encirclement inside which our kisans are expected to practice their art. The draft bill exempts kisans from registering their seeds in the proposed national registry and sub-registries (an expensive, onerous process designed for the corporate seed industry and their research partners) as a concession.

But in doing so the bill prepares the ground for future interpretation of ‘certified’ and ‘approved’ seed as looking only to the registers – and not kisans‘ collections – as being legitimate. This preparatory measure to exclude utterly ignores the mountainous evidence in the central government’s own possession – the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources – of the extraordinary cultivated, wild, forest and agro-ecological biodiversity of India.

In the cereals category (with 13 groups) the NBPGR gene bank lists 99,600 rice varieties, 30,000 wheat varieties, 11,000 maize, 8.075 barley varieties. In the millets category which has 11 groups there are 57,400 total varieties. How have all these – not exhaustive as they are – become known? Through the shared knowledge and wisdom of our kisans, whose continuing transmission of that knowledge is directly threatened by the provisions of the draft bill, once what they know is kept out of the proposed registers, designated as neither ‘certified’ nor ‘approved’ and turned into avidya.

Vital to regulation and certification are definitions and a prescription for what is ‘acceptable’. The bill says, “such seed conforms to the minimum limit of germination and genetic, physical purity, seed health and additional standards including transgenic events and corresponding traits for transgenic seeds specified… “. The term ‘transgenic event’ is one of the synonyms the international bio-tech industry uses to mean genetically modified. The draft bill’s definition of seed expressly includes ‘synthetic seeds’.

The aspect of property and knowledge taken by the draft bill is as insidious as the brazen recognition of GM technology and produce. The taking of such an aspect also signals that the bill’s drafters have side-stepped or ignored even the weak provisions in international law and treaties concerning agriculture and biodiversity which oblige signatory countries to protect the traditional and hereditary customary rights of cultivators and the protection of biodiversity. These include the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV, 1961, revised in 1972, 1978 and 1991), the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture and Food (ITPGRFA, 2001), and the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Nagoya Protocol (entered into force in 2014).

Aside from the desultory and perfunctorily monitored obligations placed upon India by these and other international and multi-lateral treaties that have to do with agriculture and biodiversity, the draft bill aggressively seeks to promote not only the import and export of ‘approved’ seeds (including seeds that are the result of GM and later gene editing bio-technologies), it submits the interpretation of its provisions to sanctioned committees and sub-committees which by design will be controlled by the the twinned proponents of industrial and technology-centric agriculture: the ICAR and supporting government agencies, and the food-seed-fertiliser-biotech multinational corporations and their subsidiaries in India.

Very distant indeed is the intent of this draft bill – and of India’s administrative and scientific cadres for the last three generations – from the consciousness that was given to us in our shruti: “Harness the ploughs, fit on yokes, now that the womb of the earth is ready, sow the seed therein, and through our praise, may there be abundant food, may grain fall ripe towards the sickle” (Rgveda 10.101.3)

यु॒नक्त॒ सीरा॒ वि यु॒गा त॑नुध्वं कृ॒ते योनौ॑ वपते॒ह बीज॑म् ।

गि॒रा च॑ श्रु॒ष्टिः सभ॑रा॒ अस॑न्नो॒ नेदी॑य॒ इत्सृ॒ण्य॑: प॒क्वमेया॑त् ॥३॥

The wholesale fibs party and its propaganda

(This article was first published by Vijayvaani and is available here.)

The Congress disinformation machine is up and running so hard that now it’s reinventing economics. An article in The Hindustan Times, dated Jan. 15, 2019 on the wholesale price index (WPI), with a wild headline, “Worst price slump in 18 years shows scale of farm crisis”, shows the Congress-plus-opposition agitprop firing on all cylinders. The trouble with this shoddy report and its very obvious promoters is that the wholesale price index (a) hasn’t behaved the way they claim it has (b) is not an indicator of the income health of the kisan household.

These minor inconveniences did not stop The Hindustan Times report from pronouncing that “This financial year, 2018-19 could end up being the worst year for farm incomes in almost two decades, government data indicates in a revelation that emphasises the gravity of the ongoing agrarian crisis”. The government data cited is the WPI which, as the name makes clear, is an index of the change in prices at the level of bulk sale, which for primary agricultural produce is at the mandi, or “farm gate”, as this reporter calls it fashionably. “The WPI sub-component for primary food articles has been negative for six consecutive months beginning July 2018. This means their prices are falling,” says the report.

This is false. Here are the WPI numbers for the category ‘primary articles – food articles’, for the months July to December (the latest month) 2018: July 144.8, August 144.8, September 144.5, October 145.9, November 146.1 and December 144.0 – where is the “negative for six consecutive months”?

Even the simple math the report claims to have done – based on a misreading of the WPI – is wrong. “The WPI sub-component for food components was -0.1% in December. It was -2.1%, -4%, -0.2%, -1.4% and -3.3% in the preceding five months,” says the report. Also false. The sequence of change, from December running backwards to July, is -2.1, 0.2, 1.4, -0.3, 0 and 3. And the change is a number, not a per cent, because the WPI and its components are indices.

Even the simple math the report claims to have done – based on a misreading of the WPI – is wrong. “The WPI sub-component for food components was -0.1% in December. It was -2.1%, -4%, -0.2%, -1.4% and -3.3% in the preceding five months,” says the report. Also false. The sequence of change, from December running backwards to July, is -2.1, 0.2, 1.4, -0.3, 0 and 3. And the change is a number, not a per cent, because the WPI and its components are indices.

But the HT report ploughs on unmindful: “The last time WPI for primary food articles showed negative annual growth for two consecutive quarters was in 1990. The disinflation in farm prices has also led to a collapse in nominal farm incomes, which was last seen in 2000-01.”

So many non-sequiturs in two sentences. A sequence of WPI numbers over several months is not an indicator of annual growth or contraction for what is being measured. As any Food Corporation of India warehouse manager could have told the reporter, what is indexed is the change.

Did the newspaper scrutinise WPI data back until 1990? If it did – and if the sponsors of this “data revelation” did – they would not have failed to notice that the current WPI series has the base year (from which index numbers of 697 different components are calculated) of 2011-12. The previous base year was 2004-05, before that it was 1993-94 and before even that it was 1981-82.

What happened instead is that The Hindustan Times was told to reference the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy which maintains the WPI data back to the 1981-82 series, but has shown a chart with the news report that draws the 2004-05 series. The rider while comparing indices from different series – that they be recalculated with a specific linking factor that makes two series intelligible to each other – is not mentioned at all by the reporter nor by those interviewed by the paper, and they are, in order of appearance: Himanshu, an associate professor of economics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University; Niranjan Rajadyaksha, research director and senior fellow at IDFC Institute, Mumbai; Praveen Chakravarty, chairman of the Congress data analytics department. And last, BJP spokesperson Gopal Agarwal.

Their quotes, and the confused graphs thrown in, are meant to prop up the sagging storyline – that the Doubling Farmers’ Income programme of the BJP is not working, that there is ‘agrarian distress’ all over India (the reason given for the INC-Left-NGO morcha to Delhi in November 2018), that the boost to minimum support prices are not working.

“To be sure,” the report says, so that we get the point that the data certainly does not make, “the current crisis in farming is related more to a crash in farm prices rather than output growth.” And immediately adds that in July 2018, “the central government increased the minimum support prices (MSPs) of 14 crops to give farmers a 50% return over their cost of production”. In fact, the MSP was raised so that it is now no less than 50% above the cost of production. Several crops have their MSPs pegged at 60% and even 70%.

“To be sure,” the report says, so that we get the point that the data certainly does not make, “the current crisis in farming is related more to a crash in farm prices rather than output growth.” And immediately adds that in July 2018, “the central government increased the minimum support prices (MSPs) of 14 crops to give farmers a 50% return over their cost of production”. In fact, the MSP was raised so that it is now no less than 50% above the cost of production. Several crops have their MSPs pegged at 60% and even 70%.

Not content with the bashing of the BJP government by those the reporter has interviewed, the newspaper then brings in still another angle, GDP (gross domestic product) data. “That disinflation in farm-gate prices has put a squeeze on farm incomes can be seen from a comparison of growth in agricultural GDP at current and constant prices,” blithely says the report.

“The first advance estimates of GDP figures for 2018-19, which were released by the Central Statistical Office (CSO) last week, show that the difference between current and constant price growth in Gross Value Added (GVA) in agriculture and allied activities was -0.1 percentage point. This differential is 4.8 percentage points for overall GVA.”

It is surprising that The Hindustan Times appears to have no access to any of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research’s agronomists, who could have been asked to clarify what the connection is, if any, between GDP growth rates, gross value added and the income of a kisan household in any of our 350 (and rising) districts that produce food for markets near and far. What matters to that household is the income realised for crop grown and sold, and this is where eNam, the electronic national agriculture market, is making a difference with, till date, 585 markets in 16 states and 2 union territories being integrated.

But the newspaper wants to press every available economics button in its frantic attempt to convince its readers that there is an agrarian crisis being engineered by the BJP government. And so it enlists the Reserve Bank of India, too, claiming that “The failure of MSP hikes to arrest the decline in farm-gate prices was taken note of by RBI as well”. What has been quoted from the RBI monetary policy committee meeting held during 3-5 December 2018 does not say so at all.

But the newspaper wants to press every available economics button in its frantic attempt to convince its readers that there is an agrarian crisis being engineered by the BJP government. And so it enlists the Reserve Bank of India, too, claiming that “The failure of MSP hikes to arrest the decline in farm-gate prices was taken note of by RBI as well”. What has been quoted from the RBI monetary policy committee meeting held during 3-5 December 2018 does not say so at all.

“The prices of several food items are at unusually low levels and there is a risk of sudden reversal, especially of volatile perishable items,” is how the RBI has been quoted. And what this means is that the consumer of food could find the weekly food bill rising; as with the other crutches this report leans on heavily, the RBI has not said what The Hindustan Times tells readers it has. The risk of the price of some food items rising is not a “decline in farm-gate prices”.

Likewise, the second quote from the RBI meeting – “available data suggest that the effect of revision in minimum support prices (MSPs) announced in July on prices has been subdued so far” – is an encouragement, far from the burden it is made out to be by the report.

Typically, a rise in the MSP would have been transferred, at least some if not most of it, by the layers of crop collection, retail and distribution, to the consumer. This transfer, said the RBI, has been subdued, which shows that the measures taken by the government to cut out profiteering middlemen are working.

Six months in 1990 are not six months in 2018. Gross value added whether at constant or current prices is in no way a measure of income for harvested crop a kisan earns at a mandi or through eNam. These and every other trick used in this report show why it is a shabby, confused, hodge-podge of opposition party innuendo that is meant to ride on data which the reading public scarcely notice. Except, when it is noticed, the whiz-bang falls flat.

Masses of cotton but mere scraps of vegetables

The sizes of the coloured crop rectangles are relative to each other based on thousand hectare measures. The four pie charts describe the distribution of the main crops amongst the main farm sizes.

For a cultivating household, do the profits – if there are any – from the sale of a commercial crop both enable the household to buy food to fit a well-balanced vegetarian diet, and have enough left over to bear the costs of its commercial crop, apart from saving? Is this possible for smallholder and marginal kisans? Are there districts and talukas in which crop cultivation choices are made by first considering household, panchayat and taluka food needs?

Considering the district of Yavatmal, in the cotton-growing region of Maharashtra, helps point to the answers for some of these questions. Yavatmal has 838,000 hectares of cultivated land distributed over 378,000 holdings and of this total cultivable area, the 2010-11 Agriculture Census showed that 787,000 hectares were sown with crops.

Small holdings, between 1 and 2 hectares, account for the largest number of farm holdings and this category also has the most cultivated area: 260,000 hectares. Next is farms of 2 to 3 hectares which occupy 178,000 hectares, followed by those of 3 to 4 hectares which occupy 92,000 hectares.

The district’s kisans allocate their cultivable land to food and non-food crops both, with cereals and pulses being the most common food crops, and cotton (fibre crop) and oilseeds being the non-food (or commercial) crops.

How do they make their crop choices? From the agriculture census data, a few matters immediately stand out, which are illustrated by the graphic provided. First, a unit of land is sown 1.5 times in the district or, put another way, is sown with one-and-a-half crops. This means crop rotation during the agricultural year (July to June) is practiced but – with Yavatmal being in the hot semi-arid agri-ecoregion of the Deccan plateau with moderately deep black soil – water is scarce and drought-like conditions constrain rotation.

Second, land given to the cultivation of non-food crops is 1.6 times the area of land given to the cultivation of food crops (including the crop rotation factor), a ratio that is made abundantly clear by the graphic. This tells us that the food required by the district’s households (about 647,000 of which about 516,000 are rural) cannot be supplied by Yavatmal’s own kisans.

The vegetables required by the populations of Yavatmal’s 16 talukas (Ner, Babulgaon, Kalamb, Yavatmal, Darwha, Digras, Pusad, Umarkhed, Mahagaon, Arni, Ghatanji, Kelapur, Ralegaon, Maregaon, Zari-Jamani, Wani) can in no way be supplied by the surprisingly tiny acreage of land allocated to their cultivation. Nor do they fare better for fruit, which has even less land (although this is a more complex calculation for fruit trees, less so for vine fruits).

Third, 125,000 hectares to wheat and 71,000 hectares to jowar makes up almost the entire cereals cultivation. Likewise 126,000 hectares to tur (or arhar) and 94,000 hectares to gram accounts for most of the land allocated to pulses. Thus while Yavatmal’s talukas are well supplied with wheat, jowar, gram and tur dal, its households must depend on neighbouring (or not so neighbouring) districts for vegetables, as a minimum of 280,000 tons per year is to be supplied to meet each household’s recommended dietary needs.

What the graphic helps us ask is the size of the costs associated with crop cultivation choices in Yavatmal. The cultivation of hybrid cotton in India’s major cotton growing regions (several districts each in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat) is associated with heavy chemical fertiliser and pesticides use. Whether the soil on which cotton has grown can be sown again with a food crop is not clear from the available data but if so such a crop would be saturated with a vicious mix of chemicals that include nitrates and phosphates.

The health of the soil in Yavatmal’s 16 talukas is probably amongst the most fragile in Deccan Maharashtra, and after years of coaxing a false ‘productivity’ out of the ground for cotton, it would be best for the district’s 516,000 rural households to take a cotton ‘holiday’ for three to four years and revert to the mixed and integrated cropping of their forefathers (small millets). But the grip of the financiers and the textiles intermediaries is strong.

Debt and kisan households

For the 21 larger states, this is the picture of how much average debt a cultivator household has incurred, and how many amongst cultivator households are in debt.

For the 21 larger states, this is the picture of how much average debt a cultivator household has incurred, and how many amongst cultivator households are in debt.

The data I have used for this chart are taken from the report, ‘Household Indebtedness in India’, which is based on the 70th Round of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, and collected during January to December 2013.

The states are plotted on average debt of such households, in lakh rupees on the left scale, and the proportion of such households, as a percentage of all such households, on the horizontal scale. The size of the circles are relative and based on the amount of average debt.

The average amount of debt per cultivator household seen in this chart is for most of the 21 larger states, lower than the overall rural household average debt of Rs 1,03,457. However the cultivator household is one of six types of rural household (the categories are: self-employed in agriculture, self-employed in non-agriculture, regular wage/salary earning, casual labour in agriculture, casual labour in non-agriculture, others). About 31.4% of all rural households are in debt.

The chart shows that cultivator households in Punjab and Kerala carry the highest amounts of debt, and that a highest percentage of cultivator households carrying debt are in Telengana and Andhra Pradesh. There are two distinct groups. One group of nine states occupies the right and most of the vertical area of the chart. The second group is of 12 states clustered towards the lower left corner of the chart panel.

This difference describes regional variation. In the first group are all the southern states. In the second are all the eastern and central states. Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand cultivator households exhibit the greatest similarity, with average debt of under Rs 40,000 and with less than 35% of cultivator households carrying debt.

Bihar, West Bengal and Odisha are likewise similar, their average debt being less than Rs 20,000. Assam, Jammu and Kashmir, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand cultivator households bear the lowest average debt and less than one in five of such households is in debt.

These are the broad brush strokes of debt amongst cultivator households in the 21 major states painted by the NSSO’s ‘Household Indebtedness in India’ report. A more detailed examination of such debt, and also the debt of the other kinds of rural households, will give us a deeper understanding of the subject.

Counting the great Indian agricultural mosaic

There is not a ‘bigha‘ of Bharat that has not been cultivated, used as orchard, or as pasture, or at one time or another over the centuries, times tumultuous or peaceable, belonged in part or wholly to a nearby ‘agrahara‘. The measurement of our land is a science that is as ancient as are the sciences of tending to and cultivating the land, and what today we reckon in hectares and acres (not ours these measures, but left behind and used through administrative inertia) were counted, re-counted, assessed and taxed as being a certain number of guntha, bigha, biswa, kanal, marla, sarsaai or shatak. In these wondrously named parcels of land – bunded and their perimeters shaded, so that the kisans of old could sit under a leafy canopy and enjoy a mid-day meal and a short snooze – grew our foodgrain.

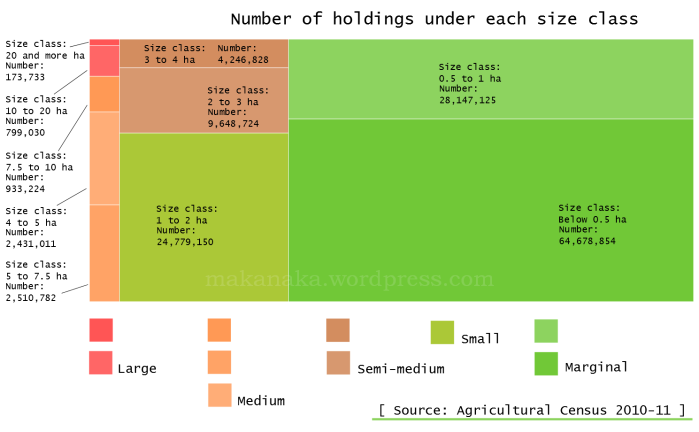

There are 138.35 million operational holdings in India. (Uttar Pradesh has 23.33 million, Bihar 16.19 million, Maharashtra 13.70 million, Andhra Pradesh 13.18 million.) The small and marginal holdings taken together (below 2 hectares) constitute 85.01% of all holdings. This treemap represents the number of holdings, relative in size to each other, in each category of land holding area.

Whether Gupta or Vijaynagar, Hoysala or Kakatiya, Mughal or British colonial, these fields every so often received visitors, at times unwelcome but usually businesslike, for the Bharat of old and of medieval times alike was profoundly productive, and these officials had much ground to cover. In later eras they were known as tehsildar, naib tehsildar, kanungo and patwari and they prepared records such as the ‘shajra nasab‘ (always with the help of a typically tattered ‘jamabandi‘), followed by the ‘khatauni‘ – a laborious task that required the patwari to measure each ‘khasra‘ and appropriately mark it with pencil (a rough marking, to be inked only after final tallying) on the ‘mussavi‘. And to be administratively infallible, for land revenue and land settlement is the most serious of a government’s business, the kanungo re-measured the land and added his observation to the ‘mussavi‘.

And so it went, from one panchayat to the next, from one circle to another, from one tehsil (or mandal or taluka) to the next, passing under the tired eyes and across the cluttered desks of assistant settlement officer (where is the inspection diary, these officers would ask), then to the assistant collector (grades II and I) and then to the spacious chambers (supplied with punkahs and water coolers) of the district collector.

The total cultivated area is 159.59 million hectares, the average size of an operational holding has declined to 1.15 hectare in 2010-11 as compared with 1.23 hectare in 2005-06. (Rajasthan has 21.14 million hectare, Maharashtra has 19.77 million, Uttar Pradesh 17.62 million, Madhya Pradesh 15.84 million.). This treemap represents the cultivated agricultural area, relative in size to each other, in each category of land holding.

It was so then, in the time of my grand-parents (two sets, at opposite ends of British India), and it was so in the time of their great grand-parents. During my lifetime it has come to be called – this detailed measuring of our land with a benign view to assessing fairly – the agricultural census, and it is the most recent one, 2010-11, which gives us many points to ponder, but is somewhat lacking when it comes to the labyrinthine histories of the administering of what for so many centuries has been measured and recorded.

Nonetheless the Agricultural Census of India 2010-11 serves us with a commentary that is contemporaneous and informative, for its primary fieldwork consisted of “retabulating the operational holding-wise information contained in the basic village records” which “would be done by the village accountant”, a gentleman (usually, for accounting has not experienced the gender equalising which panchayats have) known in different states by different names – he is the patwari but he is also the lekhapal, the talathi or the karnam. His work (always in progress, just as the seasons are) is supervised by the revenue inspectors.

These worthies (not as dour, I can assure you, as their title suggests, for they are just as often cultivators themselves, or veterinarians, and even ayurvedic practitioners) contribute to the most important part of our agricultural census, and that is the preparation of the list of operational holdings. It is a task far too wide and vast and complex for any revenue inspector, however dedicated and well disposed towards both the physical and mathematical aspects of it, for this officer must examine all the survey numbers in the basic village record, the ‘khasra register’ (or any other equivalent local record), classify the survey numbers held by operational land holders, often cross-reference this tentative list with other village records (like the ‘khatauni‘) which names the cultivators. Many consultations ensue, a few arguments, and a considerable amount of cross-confirmation in dusty stacks and mouldy cupboards.

This is the historical milieu to which our agricultural census belongs. We should savour it, for it is a unique undertaking, just as much as each of our thousands of varieties of rice (‘dhanyam‘ it was in the time of the ‘agraharas‘ and it is so today too) – the careful and ritual counting of the great Indian agricultural mosaic.