Posts Tagged ‘GIEWS’

A method for a post-carbon monsoon

The uses to which we have put available climatic observations no longer suit an India which is learning to identify the impacts of climate change. Until 2002, the monsoon season was June to September, there was an assessment in May of how well (or not) the monsoon could turn out, and short-term forecasts of one to three days were available only for the major metros and occasionally a state that was in the path of a cyclone. But 2002 saw the first of the four El Niño spells that have occurred since 2000, and the effects on our Indian summer monsoon began to be felt and understood.

The India Meteorology Department (which has become an everyday abbreviation of IMD for farmers and traders alike) has added computational and analytical resources furiously over the last decade. The new research and observational depth is complemented by the efforts of a Ministry of Earth Sciences which has channelled the copious output from our weather satellites, under the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), and which is interpreted by the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), to serve meteorological needs.

The IMD, with 559 surface observatories, 100 Insat satellite-based data collection platforms, an ‘integrated agro-advisory service of India’ which has provided district-level forecasts since 2008, a High Performance Computing System commissioned in 2010 (whose servers run at Pune, Kolkata, Chennai, Mumbai, Guwahati, Nagpur, Ahmedabad, Bengaluru, Chandigarh, Bhubaneswar, Hyderabad and New Delhi) ploughs through an astonishing amount of numerical data every hour. Over the last four years, more ‘products’ (as the IMD system calls them) based on this data and its interpretation have been released via the internet into the public domain. These are reliable, timely (some observation series have three-hour intervals), and valuable for citizen and administrator alike.

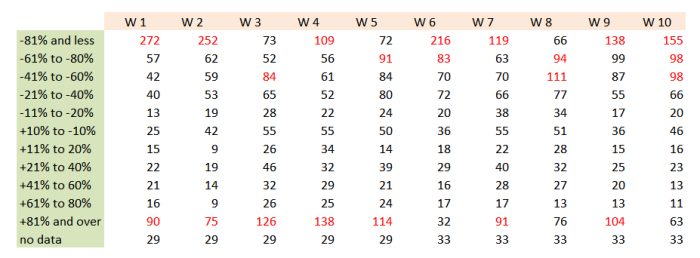

The new 11-grade indicator for assessing weekly rainfall departures in districts. Same data, but dramatically more useful guidance.

Even so, the IMD’s framing of how its most popular measures are categorised is no longer capable of describing what rain – or the absence of rain – affects our districts. These popular measures are distributed every day, weekly and monthly in the form of ‘departures from normal’ tables, charts and maps. The rain adequacy categories are meant to guide alerts and advisories. There are four: ‘normal’ is rainfall up to +19% above a given period’s average and also down to -19% from that same average, ‘excess’ is +20% rain and more, ‘deficient’ is -20% to -59% and ‘scanty’ is -60% to -99%. These categories can mislead a great deal more than they inform, for the difference between an excess of +21% and an excess of +41% can be the difference between water enough to puddle rice fields and a river breaking its banks to ruin those fields.

In today’s concerns that have to do with the impacts of climate change, with the increasing variability of the monsoon season, and especially with the production of food crops, the IMD’s stock measurement ‘product’ is no longer viable. It ought to have been replaced at least a decade ago, for the IMD’s Hydromet Division maintains weekly data by meteorological sub-division and by district. This series of running records compares any given monsoon week’s rainfall, in a district, with the long period average (a 50-year period). Such fineness of detail must be matched by a measuring range-finder with appropriate interpretive indicators. That is why the ‘no rain’, ‘scanty’, ‘deficient’, ‘normal’ or ‘excess’ group of legacy measures must now be discarded.

In its place an indicator of eleven grades translates the numeric density of IMD’s district-level rainfall data into a much more meaningful code. Using this code we can immediately see the following from the chart ‘Gauging ten weeks of rain in the districts’:

1. That districts which have experienced weeks of ‘-81% and less’ and ‘-61% to -80%’ rain – that is, very much less rain than they should have had – form the largest set of segments in the indicator bars.

2. That districts which have experienced weeks of ‘+81% and over’ rain – that is, very much more rain than they should have had – form the next largest set of segments in the indicator bars.

3. That the indicator bars for ‘+10% to -10%’, ‘-11% to -20%’ and ‘+11% to +20%’ are, even together, considerably smaller than the segments that show degrees of excess rain and degrees of deficient rain.

Far too many districts registering rainfall departures in the categories that collect extremes of readings. This is the detailed reading required to alert state administrations to drought, drought-like and potential flood conditions.

Each bar corresponds to a week of district rainfall readings, and that week of readings is split into eleven grades. In this way, the tendency for administrations, citizens, the media and all those who must manage natural resources (particularly our farmers), to think in terms of an overall ‘deficit’ or an overall ‘surplus’ is nullified. Demands for water are not cumulative – they are made several times a day, and become more or less intense according to a cropping calendar, which in turn is influenced by the characteristics of a river basin and of an agro-ecological zone.

The advantages of the modified approach (which adapts the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s ‘Global Information and Early Warning System’ categorisation, designed to alert country food and agriculture administrators to impending food insecurity conditions) can be seen by comparing the single-most significant finding of the IMD’s normal method, with the finding of the new method, for the same point during the monsoon season.

By 12 August 2015 the Hydromet Division’s weekly report card found that 15% of the districts had recorded cumulative rainfall of ‘normal’ and 16% has recorded cumulative rainfall of ‘deficient’. There are similar tallies concerning rainfall distribution – by region and temporally – for the meteorological sub-divisions and for states. In contrast the new eleven-grade measure showed that in seven out of 10 weeks, the ‘+81% and over’ category was the most frequent or next-most frequent, and that likewise, the ‘-81% and less’ category was also the most frequent or next-most frequent in seven out of 10 weeks. This finding alone demonstrates the ability of the new methodology to provide early warnings of climatic trauma in districts, which state administrations can respond to in a targeted manner.

Mapping climate behaviour, ten days at a time

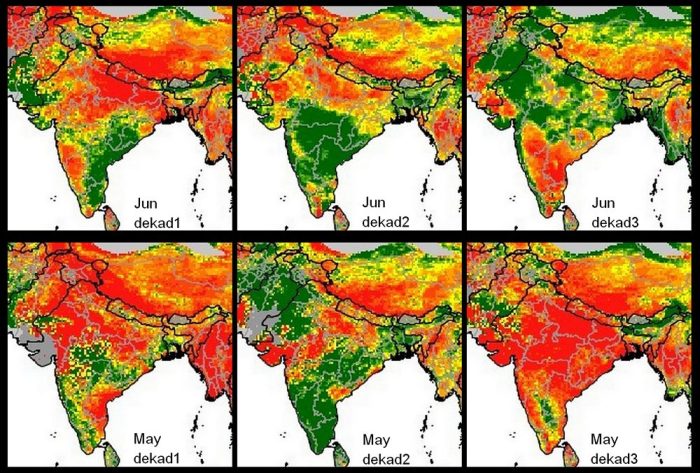

This year, the Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS, a project of the FAO) has brought into public domain a new rainfall and vegetation assessment indicator. The indicator takes the form of maps which describe conditions over blocks of ten days each, with each such block termed a dekad (from the Greek for ‘ten’). Thus we have visual views of divisions of thirds of a month which from a crop cultivation point of view, now lies between the weekly and fortnightly assessments regularly provided by agri-meteorological services.

How to read the colours used in the rainfall anomaly maps.

In 2015, what was quickly called “out of season” rainfall was experienced in most of India during March and April. These conditions carried over into May and that is why the typical contrast between a hot and rainless May and a wet June is not seen.

The panel of maps shows the incidence of normal, below normal and above normal rain during six dekads of May and June. Greens signal above normal, yellows are normal and reds are below normal. The first dekad of May looks like what the second week of June normally does, but for the large above normal zone in the north-central Deccan. The second dekad of May has in this set had the largest number of above normal points, with more rain than usual over the southern peninsula, and over Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal. Rajasthan and Punjab.

The third dekad of May shows most of India as far below normal. This changes in the first dekad of June, with rain over the eastern coast registering much above normal for the period – Tamil Nadu, Rayalaseema, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. During the second dekad of June, the divide north and south of the Vindhyas is visible, when northern India and the Gangetic belt continued to experience very hot days whereas over Telengana, Karnataka, Vidarbha and Madhya Maharashtra there was above normal rainfall. During the third dekad of June the picture was almost reversed as the southern states fell below their running rainfall averages.

This panel describes not rainfall but the anomalies (above and below) recorded in received rainfall. At the level of a meteorological sub-division or a river basin, the anomaly maps are a quick and reliable guide for judging the impacts of climate variability on crop phases (preparation, sowing, harvest) and on water stocks.

Cereals shock, an early indicator using FAO data and outlook

To what extent do cereals prices pull up (or depress, if at all they do) the FAO food price index? This chart shows the relationship between the main index and the cereals sub-index. As we can see from the shaded areas (which correspond roughly to the 200 mark), the steady steep rise in the cereals index, from around 2007 August onwards, pulled first the cereals sub-index and then the FAO food price index over 200, and kept them above for about nine months. The same phenomenon took place from 2010 July onwards, as a soaring cereals sub-index shot above the main index and pulled it up above 200 in 2010 October, and has kept both above 200 ever since.

To what extent do cereals prices pull up (or depress, if at all they do) the FAO food price index? This chart shows the relationship between the main index and the cereals sub-index. As we can see from the shaded areas (which correspond roughly to the 200 mark), the steady steep rise in the cereals index, from around 2007 August onwards, pulled first the cereals sub-index and then the FAO food price index over 200, and kept them above for about nine months. The same phenomenon took place from 2010 July onwards, as a soaring cereals sub-index shot above the main index and pulled it up above 200 in 2010 October, and has kept both above 200 ever since.

Now FAO has said (in its global information and early warning system on food and agriculture, GIEWS) that the export prices of grains has risen sharply in 2012 July with maize prices at record levels. Export prices of maize increased by 20% in the first three weeks of July compared to their June level. The benchmark US maize price averaged USD 322 per tonne reaching a new record high. “Prices were underpinned by continuous concerns about the impact of hot and dry weather conditions on yield potential of the 2012 maize crop in parts of the United States,” said FAO. And now has come the downward revision of the US official 2012 maize production forecast.

The question for us is: how will the the FAO Food Price Index, which in June fell for the third consecutive month, respond? The FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) averaged 201 points in June 2012, down 4 points (1.8%) from a May value of 205 points. After the third consecutive month of decline, the June value of the index was 15.4% below the peak reached in February 2011. “Continued economic uncertainties and generally adequate supply prospects kept international prices of most commodities under downward pressure, although growing concerns over adverse weather sustained prices of some crops toward the end of the month,” said the FAO.

The question for us is: how will the the FAO Food Price Index, which in June fell for the third consecutive month, respond? The FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) averaged 201 points in June 2012, down 4 points (1.8%) from a May value of 205 points. After the third consecutive month of decline, the June value of the index was 15.4% below the peak reached in February 2011. “Continued economic uncertainties and generally adequate supply prospects kept international prices of most commodities under downward pressure, although growing concerns over adverse weather sustained prices of some crops toward the end of the month,” said the FAO.

In 2012 June, the FAO Cereal Price Index averaged 221 points, unchanged from May and down 45 points (16.8%) from its peak of 265 points in April 2011. Grain prices were very volatile in June, with weather as the main driver. “After a generally subdued situation during the first half of the month, markets moved up in the second half amid deteriorating crop prospects, most notably for maize in the United States,” said the FAO.

Finally, FAO’s cereal supply and demand brief for 2012 July lowered the forecast for world cereal production from last month, which is likely to result in a smaller build-up of world inventories by the end of seasons in 2013 than previously anticipated. “While the bulk of the increase in cereal production from last year is still expected to originate from a significant expansion in maize production in the United States, the deteriorating crop conditions due to the continuing dryness and above-average temperatures in much of the major growing regions of the country have dampened this outlook,” said the brief.

Moreover, world wheat production is heading toward a contraction of about 3.2%, to 678 million tonnes, or 2 million tonnes less than reported in June, as downward adjustments in Australia, China and the Russian Federation more than offset upward revisions in the EU and Morocco. Where rice production in 2012 is concrened, the FAO estimate is it will grow by 1.6% to 489.1 million tonnes (in milled equivalent), which compares with a previous forecast of 490.5 million tonnes. The small reduction mainly reflects some deterioration of prospects in a few major producing countries, especially India.

Winter drought threatens China wheat production

Urbanisation in agricultural plains, visible from the flight path close to Beijing. Photo: Rahul Goswami

The FAO has just released a special briefing on wheat production in China, through its Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS). “A severe winter drought in the North China Plain may put wheat production at risk,” said the FAO. “Substantially below-normal rainfall since October 2010 in the North China Plain, the country’s main winter wheat producing area, puts at risk the winter wheat crop to be harvested later in the month of June.”

Low precipitation resulting in diminished snow cover has reduced the protection of dormant wheat plants against frost kill temperatures (usually below -18°C) during winter months from December to February. Low precipitation and thin snow cover have also jeopardized the soil moisture availability for the post-dormant growing period. Thus, the ongoing drought is potentially a serious problem.

FAO’s GIEWS said that the main affected provinces include Shandong, Jiangsu, Henan, Hebei and Shanxi, which together represent about 60% of the area planted and two-thirds of the national wheat production. According to official estimates some 5.16 million hectares out of the total of about 14 million hectares under winter wheat may have been affected in these provinces. The drought has reportedly affected some 2.57 million people and 2.79 million livestock due to the shortages of drinking water.

So far there have been some positive developments, such as the relatively mild temperatures, particularly the absence of frost kill temperatures, and the lower than average sub-zero temperature days. This combined with increased supplementary irrigation made available by the Government is likely to compensate to some extent the negative impact of low snow fall and low moisture availability. However, adverse weather, particularly extreme cold temperatures could still devastate yields. The Government has allocated some USD 15 billion to support farmers’ incomes and subsidize the costs of diesel, fertiliser and pesticide.

This drought in north China seems to be putting further pressure on wheat prices, said FAO, which have been rising rapidly in the last few months. In January 2011 the national average retail price of wheat flour rose by more than 8% compared to two months earlier and stood at 16% higher than a year earlier. Although the current winter drought has, so far, not affected winter wheat productivity, the situation could become critical if a spring drought follows the winter one and/or the temperatures in February fall below normal.